James Timpson knows the secret to making money – very happy staff

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A bottle of champagne plus the day off on your birthday; free breakfast before 9am and subsidised chef lunches; a £1,000 Weekly Lottery, a state of the art gym and free-to-use luxury holiday homes. Just some of the benefits of working for James Timpson OBE, the sixth generation leader of the family firm.

The latest labour market figures from the Office for National Statistics show we’re in the grip of a worklessness crisis, with 9.3 million people in the UK economically inactive. Meanwhile, new data from the Resolution Foundation reveals that Gen Z and people in their 20s are more likely to be off work than older people.

Could the bag of carrots approach advocated by Timpson get the UK back to work? He certainly thinks so.

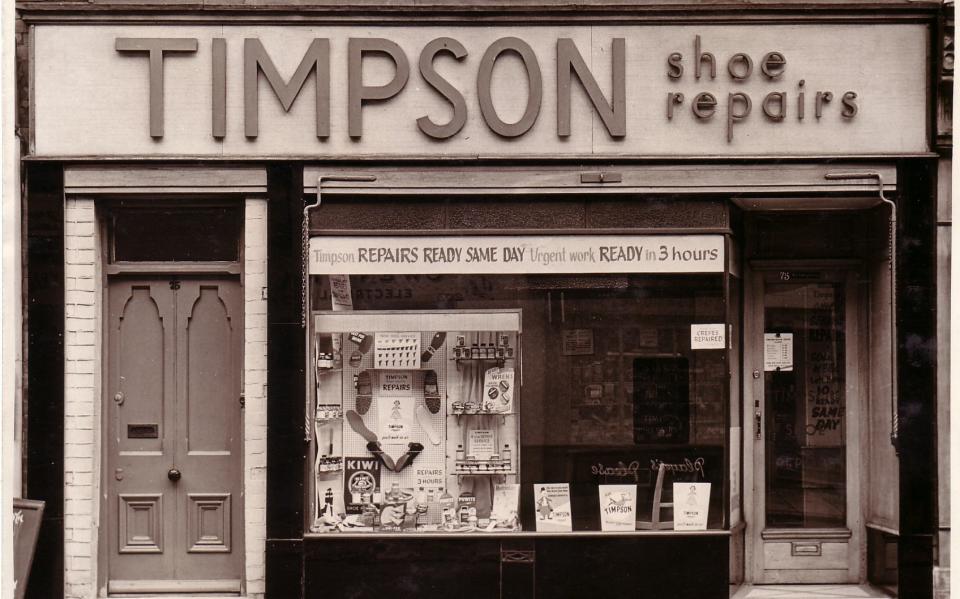

If you know anything about Timpson, which was founded in 1865, it will be that apart from getting the public out of key and shoe repair sticky wickets, they have a policy of employing ex-offenders; something that James pioneered after he became the chief executive in 2002.

“People think everyone who works for Timpson has spent time in prison, but it’s really only one in nine,” he says.

The policy is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Timpson’s feel-good credentials.

With days off for pet bereavement or when your child starts school, the company culture stands in stark contrast to most workplaces, where the idea of booking a doctor’s appointment can feel like a covert operation.

If you work for Timpson, or one of its other brands, which includes Max Spielmann, Johnsons The Cleaners, Snappy Snaps, Jeeves of Belgravia and The Watch Lab, then you’re part of the family. Timpson prefers to call his employees “colleagues”. It may sound very Kumbaya, but there’s business sense behind the generosity.

Because Timpson has found that the more he spends on his colleagues happiness, the more money they make.

It’s a paradigm shift that’s seen him institute a Happy Index. Rather than scrutinising the sales figures, Timpson rates his colleagues’ happiness. And without fail, the area managers with the highest happiness scores also happen to be making the most profit.

“If someone is unhappy then the sales are often down and there are more customer complaints and more sick days,” explains Timpson.

More often than not, the main reason someone is unhappy is because of problems at home; elderly relatives, mental health, childcare.

Life, in short. What Timpson has done is create a work environment that supports its employees with these challenges, acknowledging the balance between life and work.

His experience has solidified the belief that instead of focusing on budgets and forecasts, managers should “just spend your time trying to make sure your colleagues are happy. It’s way cheaper, and much more fun. And that’s how you make money.”

The self-styled Director of Fun is speaking on Zoom from a company-owned chalet in Morzine, France. It’s a change from his usual work routine, where he spends at least two days a week visiting stores and talking to colleagues.

Timpson House (more egalitarian than calling it HQ) on the outskirts of Manchester in Wythenshawe is where he and a team of 700 support the 3,500 colleagues in the shops and 250 in the warehouses.

As a nation we’re lingering under a pandemic malaise and Timpson thinks he has found the formula to get us working again; less stick and plenty of carrots.

“For some people, lockdown was the best experience they’ve had in years. And I don’t think that’s a positive thing,” he says.

Timpson recalls sending everyone home at the start of the pandemic on 100 per cent pay “thinking it would be over in four weeks”. While he and five others stayed in the office trying to work out how to navigate a retail business through the crisis, his furloughed colleagues shared photos of them enjoying the incredible spring weather. “Some were in paddling pools drinking lager at 11am in the morning,” smiles Timpson.

It is why he’s not surprised that business has struggled to get people back into the office.

“It gave some people an opportunity to, how can I put this politely? To take their foot off the gas so far as ambition and work,” says Timpson.

Today, in 2024, he thinks some people want that to carry on. “And it can’t.”

Timpson was already an attractive place to work before the pandemic, with most happy to return to work. They offer super flexible working hours, and colleagues are expected to attend school assemblies, sports days and parents evenings. (“You can bring your children into the office, you can bring your dog even,” he says). However, Timpson is not a “work from home” business.

He adds: “It’s pretty clear that businesses work best when people are in the office, but that’s only if the office is a good place to be.”

He has visited his fair share of dull and uninspiring offices: “Some that are so unfriendly that I’d rather be at home as well.”

Timpson compares the office to a restaurant. “If the food was miserable and the waiter terrible and the lighting all wrong, then nobody would go.”

All of this might sound like the antithesis of a serious workplace, solving problems and being productive, and he concedes that not everyone “gets” the culture he’s created: “Some people love rules, boundaries and process. If they come into our business where they can do what they want, they struggle.”

However, underlying all of the perks and freedom is a culture of conscientiousness. “We never ask people where they are. We just trust people. And when you trust people, they are far more likely to do it than if you measure people.”

Given that he gives away a million pounds a year to Timpson’s Dreams Come True scheme (last week he awarded dental work to an ex-offender colleague who had written saying he feels too embarrassed to smile at his grandchildren) does the Happy Index really not hit their profit margin? Timpson Group pre-tax profits totalled £40.64m in the 53 weeks to October, 2022, up from £24.53m in the year before.

“Not at all,” he insists. “The more you do for colleagues, the more money you make. I don’t understand it.”

His brand of ethical capitalism is one that he’d like to see spread throughout the UK, and he’s written a book, The Happy Index, about a kind and thoughtful approach to working. They’re practices he wants to share, even if that means losing some of their competitive edge in the process. Already Greggs, a company he hugely admires, has started recruiting from prisons, which he applauds. But then, he nicked the idea of giving birthdays from his mate who owns Millie’s Cookies. “Now I would say most of the employers I know in the north west give their employees their birthday off. It’s a normal thing and that’s really good. It’s a small part of the cake mix to help businesses perform better.”

He dislikes the idea that business is about winning at any cost, promoted by The Apprentice, saying it promotes a false idea of what being in business entails. “It’s much more collaborative and collegiate.”

The emergence of the B corp business movement, which urges members to stand against all forms of oppression and provides a certification scheme, is encouraging. If more businesses went down this route he says it would be benefit the economy. “What would happen is that they would just perform better and their financial results would be better,” he adds. “They would be able to grow and take on more businesses that have failed. They would be able to do more of what they’re doing.”

Inevitably though, won’t employees take all of this for granted and settle into their new normal? Even Timpson admits he is constantly having to find new ways to “amaze” his workforce. Often he prefers it if a young employee leaves for a year to see that the grass isn’t necessarily greener.

But it’s not just a case of spoiling his colleagues in order to buy their happiness and thus, hard work. Timpson says it’s about giving them a sense of purpose.

“It’s a really important job serving the public. We’re helping the public with something they can’t do themselves. And we’re going to frame it in such a way that you feel it’s a valuable job and you feel valued.”

Unsurprisingly as someone who still has a strong presence on the High Street (as well as in out of town shopping centres), despite the aroma of terminal decline, it is here to stay, he says. “They’re just changing. If you think of them as buildings then there is a future for them in terms of entertainment and hospitality.”

John Lewis is a business with whom he feels Timpson is culturally aligned. With the Partnership in rocky territory, he wonders if they have lost their way when it comes to customer service.

“They need to invest in amazing customer service and amazing looking stores and then they’ll be OK. Lots of department stores have gone, so there is a space for that kind of business, but they’ve got to execute it really well,” he says. Marks & Spencer, by contrast, is on the frontfoot right now.

“People like spending their money with businesses that are on the front foot. You can tell when a business is confident and Marks and Spencers is a really good example.”

Of the UK in general, he believes there is a lack of confidence – and ambition. “But there are so many amazing things happening in the UK, so many amazing businesses and talented creative people. We need to rediscover the mojo we had in London 2012.”

His daughter is on the M&S graduate training scheme: “She really loves it. They really invest in their graduates.” His two sons have recently joined the family business. One at Max Spielman, the other at Timpson. “The kids have worked out what a 25-day holiday actually means. It’s not much,” he laughs.

They might have the Timpson surname, but, he adds: “They’ve got to put the shift in like everybody else.”

At the core of Timpson’s philosophy is that if we’re all going to be sharing space on the same work boat, then we might as well all be paddling together.

“What amazes me is that the higher up a business you go, the more flexibility, holiday and money you get. But when you own a business like I do, no one tells me how many holidays I have. It’s not fair if we have one rule for me and another for the others.”

The Happy Index by James Timpson, published by HarperCollins, is out now.