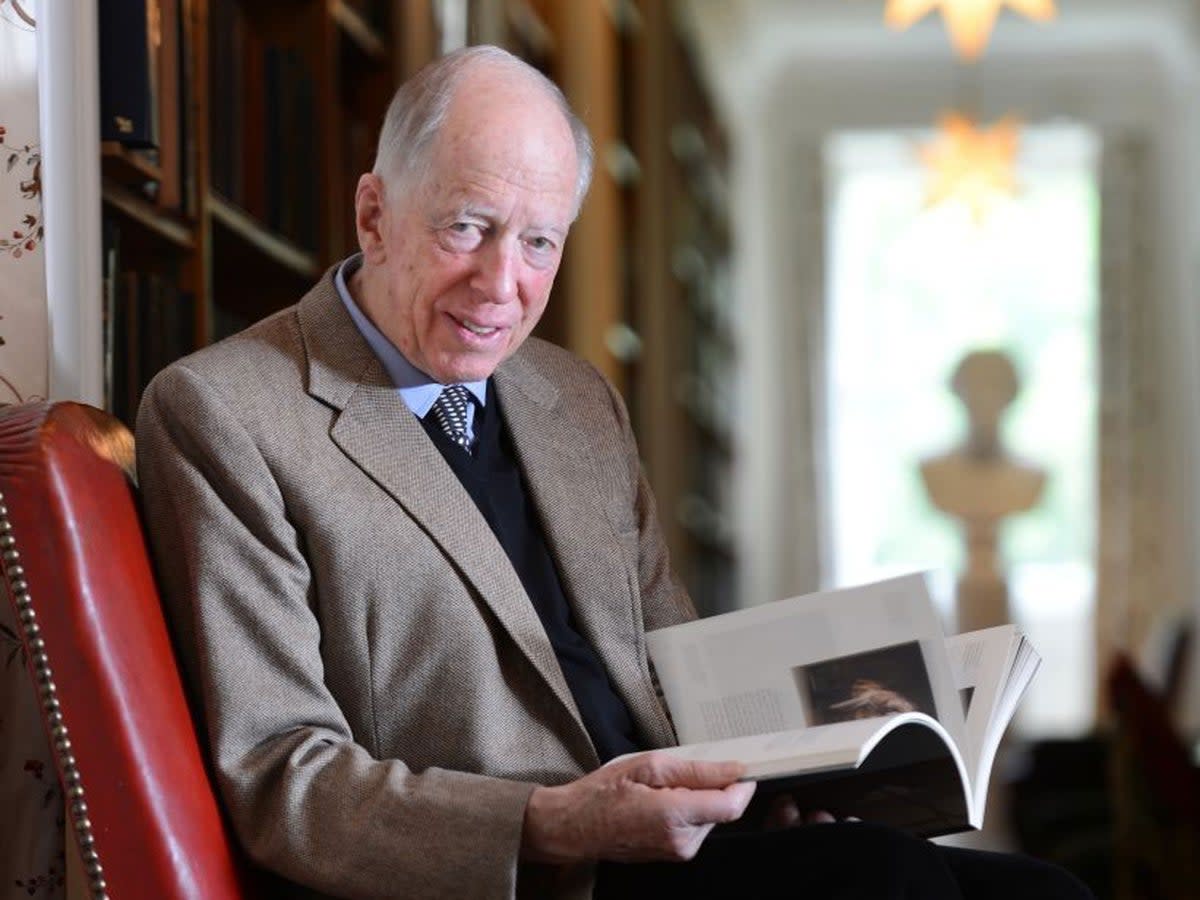

Jacob Rothschild instilled respect, fear and excitement in those he came across

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the City they’ve been shaking their heads. “It would never happen in Jacob’s day.”

They’re referring to the trauma at St James’s Place, Britain’s biggest wealth manager, which has seen its shares crash amid allegations of overcharging clients. The firm has put aside £426m for potential refunds to aggrieved customers.

Analysts at Bank of America are saying this is the “culmination of an annus horribilis” for St James’s, which is based in Cirencester and oversees £168.2bn for nearly one million clients.

If this is the end, it may survive, but another significant reputational issue might be enough to send it under. Either way, the episode has caused City veterans to remember St James’s as how it once was. They’ve been prompted to do so as well by the death, coincidentally also this week, at 87 of co-founder Jacob Rothschild.

Together with his late business partners, Sir Mark Weinberg and Mike Wilson, Lord Rothschild founded St James’s Place in 1997. The trio long since ceased to have anything to do with the firm. The consensus is they would not have let their company descend into such a mess. In their day, St James’s was built on discretion, care and rigorous analysis.

In recent years, the outfit has been dogged by controversy, criticised for high-pressure sales tactics. Advisers were given Montblanc pens, Mulberry bags and all-expenses holidays. Never, back in Jacob’s time.

It’s a measure of Rothschild’s stature that in the City he only requires introduction by his first name. Everybody knows who they’re referring to.

He was a towering figure. Tall, stooped, impeccably mannered and dressed, blessed with a burning intellect and user of few words, Rothschild was someone who was forever watched, always at the centre of speculation, for any clue, a sign of what he was going to do next.

He was a shrewd judge of character, with an ability to spot a weakness and an inquisitorial nature. A coffee with him was akin to being back in a university tutorial. Once, I was with him when he asked a question of my somewhat verbose companion. Before he could answer, Jacob said: “Why don’t you start with the ending.”

Rothschild instilled respect, fear and excitement in those he came across. A member of the eponymous banking dynasty, he discarded the silver spoon, splitting with the family bank and falling out with Evelyn de Rothschild, its head and his cousin. Jacob went on to create two hugely successful financial powerhouses, the investment trust RIT Capital and St James’s Place.

He was more than that, though. He was the last of the London buccaneers who stalked business at home and abroad decades ago, putting together audacious takeover bids, striking spectacular deals. Along with James Hanson, Gordon White, Jimmy Goldsmith, Arnold Weinstock, Tiny Rowland, Jacob Rothschild would spring surprise after surprise, catching the City unawares, keeping the markets second-guessing. They played by the rules when they were required to, but preferred if they could, to follow their own.

They were sometimes friends as well as rivals, titans who treated the Square Mile and Wall Street as means to an end. In 1989, huge excitement was caused by the sudden announcement of a press conference at the headquarters of Hambros Bank. There were Rothschild, Goldsmith and the Australian tycoon, Kerry Packer. They were going to buy BAT or British American Tobacco for £14bn.

Unnoticed, they had set up a company called Hoylake. It was to be their bid vehicle. They’d planned the deal in Simpsons in the Strand, in the Grill Room. They’d booked all the nearby tables so they could not be overheard. BAT had no idea what was coming. Its statement, describing the attack as “unsolicited and unwelcome” was hysterically understated; BAT was rocked to its core.

In the end, the trio’s strike foundered. But it was not through want of trying. That was always the point with them – nothing was too big, too remote, if they wanted it and it met their criteria, they would go for it.

While it was a serious business, running up eye-watering advisory fees and engaging in many hours of preparation, there was always an element of sport to what they did. They frequently brought the same zeal and focus to other aspects of their lives – be it fine art collecting, racehorses, wine (when he died, Jacob had 15,000 bottles in his cellar), houses or women.

Jacob, though, stood out. He was happily married to Serena for 58 years until her death in 2019. Together they transformed numerous properties, including their villa at Corfu, house at Pewsey and the Rothschild estates at Waddesdon and Eythrope and Spencer House. It was at the latter that Rothschild made his London base, acquiring neighbouring plots in St James’s Place, so much so that it earned the sobriquet “Jacob’s Place”.

For Jacob, commerce was the route to wealth which he then used to indulge in his passion for the arts and philanthropy. This distinguished him from many in the City. Of course, he amassed a great personal fortune but he also shared his money around, whether it was via the National Gallery, which he chaired, Courtauld, Somerset House, Ashmolean – the list goes on. His eyes would twinkle as he would much rather discuss a particular work or building restoration than the financial performances of his companies. But they were there, motoring away, netting him more funds to plough back.

While the City had moved on from his idiosyncratic style of doing business and that of his fellow takeover merchants (hostile takeovers are virtually unheard of today), Rothschild leaves a gaping hole. The arts, for one, has lost an enormous, enthusiastic supporter.

It would be sad indeed, if his passing was marked by the collapse of St James’s Place. The present crop should seek inspiration from his going, and ask themselves, what would Jacob have done? And there would be their answer.