'I've Created a Monster!' On the Regrets of Inventors

One of pepper spray's developers is criticizing its use at recent protests. An inventor can't control his creation, but he can try.

The reaction to the pepper-spraying incident as UC Davis last week has been nearly uniformly one of horror (I say nearly because of the credulous acceptance of the police actions by certain Fox News anchors). But to those outside of the Fox News bubble, the pepper-spray attack demonstrated a disturbing combination of callousness and aggression.

Interesting, those people include Kamran Loghman, one of pepper spray's developers. Loghman worked for the FBI in the 1980s and helped to make it into a weapons-grade material. He has also helped to write guidelines for police departments for using the spray. The New York Times found him and asked him what he made of the UC Davis incident. He told them, "I have never seen such an inappropriate and improper use of chemical agents."

And that's the thing about building weapons-grade technologies: You can't control their use.

Of course, Loghman is not the first inventor to see his creation used in a way that met with his disapproval. Alfred Nobel may be the inventor most closely associated with that sentiment, but this turns out not be quite accurate. The story goes that after inventing dynamite, he tried to make amends for it by endowing the peace prize that bears his name. But Nobel's ideological trajectory was much less clear. He believed that dynamite would help governments achieve peace through deterrence, and worked late into his life developing new weapons. He did not live to see World War I and the damage that dynamite could wreak.

A better example of an inventor with regrets is Albert Einstein, who played almost no role in the development of the atomic bomb but whose discoveries led to it. In his biography of Einstein, Walter Isaacson dramatically tells the moment when the scientist first understood the possibility of the bomb:

Sitting at a bare wooden table on the screen porch of the sparsely furnished cottage [on Long Island], [Leo] Szilard explained the process of how an explosive chain reaction could be produced in uranium layered with graphite by the neutrons released from nuclear fission. "I never though of that!" Einstein interjected. He asked a few questions, went over the process for fifteen minutes, and then quickly grasped the implications.

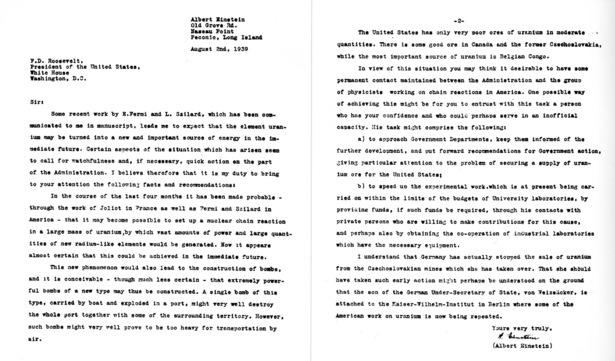

At first Einstein believed the Germans would produce the bomb, and he signed a letter to President Roosevelt urging him to support the research of American physicists into the chain reaction. Einstein never worked on the development of the bomb himself because the U.S. government would not give him the necessary clearance.

Years later, Einstein came to deeply regret his letter to Roosevelt. "Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in producing an atomic bomb," he said "I would have never lifted a finger."

Loghman's regrets are not the same as Einstein; the technology he helped to develop is orders of magnitude less harmful than atomic weapons. But his struggle is much like Einstein's. Einstein sought to control nuclear weapons and to develop institutions such as the UN that he believed could lead to peace. Loghman develops guidelines for the use of pepper spray and helps police officers get proper training. But guidelines and institutions will never control an invention completely; the inventor will not maintain perfect control, and society will have its way.

Image: Wikimedia Commons.

* * *

Below, a just-for-fun bonus: the letter Einstein sent to Roosevelt (also via Wikimedia Commons).

More From The Atlantic