Israeli font designers preserve the memories of Oct. 7 victims through their handwriting

The regular swirl of a dalet replaced by zigzag. A dramatically extended tail of a tav. The already tiny yod made yet smaller, down to just an ever-so slightly pointed dot. How a lamed in the middle of a word looks like an S, but one at the end of one looks more like a C.

Everyones handwriting features its own distinctive features and style, the thing that sets it apart from all of the others.

“I believe that within those letters, something from their soul comes out of that,” said Leah Marmorstein-Yarhi, who is spearheading a new grassroots initiative to preserve the handwriting of the people killed on Oct. 7 and in the subsequent war against Hamas.

The initiative is called Ot.Hayim, a Hebrew play on words, which translates to both “sign of life” and “letter of life.” For the project, font designers use handwriting samples of victims to create fonts that can be downloaded for free from its website.

“We believe that the ‘something from their soul’ will come out in these fonts,” Marmorstein-Yarhi told eJewishPhilanthropy. “Its a kind of digital memorial.”

Marmorstein-Yarhi said the guiding concept behind the project can be best explained by a poem by Haim Guri from his 2015 book, Though I Wished for More of More: “Know that time, enemies, the wind and the water/ Will not erase you/ You will continue, made up of letters/ That is not a little/ Something, after all, will remain of you.” That poem appears atop the Ot.Hayim website.

The idea first came about when a friend of Marmorstein-Yarhi, Yael Masika Maimon, contacted her because one of her daughter’s friends, Niv Raviv, was murdered in the attack on Kibbutz Kfar Aza. “They wanted to create a font from Niv’s handwriting,” Marmorstein-Yarhi said.

That initial request prompted her to develop the infrastructure for the project, finding font designers who were willing to volunteer through design WhatsApp groups and creating the website. “Our hearts were open. We wanted to give, to help, to do something to ease the suffering of the families,” Marmorstein-Yarhi said.

A number of other volunteers quickly came on board to run the project, including Masika Maimon, who coordinates with the families of the victims, as well as Shana Koppel, Atara Uzan, Yossi Biton and Moshe Chai Aton. Koppel, who oversees the “professional” aspects of the operation, is also one of the font designers.

“I got involved through a WhatsApp group for graphic designers in Israel,” she said. “I offered my help on the technical side.”

Koppel is one of the relatively few font designers working in Israel. “Not a lot of people make fonts, and not a lot of programs support Hebrew,” she explained.

Koppel was brought on to create the font of Raviv’s handwriting as a pilot project for Ot.Hayim. “It’s a very technical process, especially if someone else has made the letters for you,” Koppel told eJP.

She would have to go through all of the different variations of each letter, deciding which one was the “root shape,” the archetypal Aleph that all of her other Alephs are based on. “Each letter is unique, so deciding this is the letter that I’m going to pick and this is the letter that Im not is a surprisingly difficult choice,” she said.

Her handwriting was “all curves, round and full of loops,” Koppel said. It was also Raviv’s Yod that is just a dot with an almost imperceptible tail.

Though she’s never studied graphology, Koppel said that going through the handwriting of Raviv and the other victims gave her insight into their personalities. “Every letter that she wrote was telling me something about Niv,” Koppel said. “Or there would be some masculine guy who was killed fighting, but then you see that his handwriting is so neat and round, and you go, ‘Oh, that’s who you are.’”

Marmorstein-Yarhi recalled the handwriting of Lt. Col. Salman Habaka, a tank officer from a Druze village who was killed while fighting in Gaza on Nov. 2. It’s the tail of Habaka’s Tav that sometimes extends so far it underlines the entire word that follows it and then some.

“Salman: He was such a Zionist!” she said. “He wrote only in Hebrew, but you can see the Arabic in his handwriting.”

In the case of Savyon Chen Kipper, who was studying visual communication at the Holon Institute of Technology and was murdered at the Nova music festival, her handwriting didn’t reveal a hidden part of her character but rather her passion for design.

In her handwriting sample — notes from her classes —each letter is written just so. It’s her Dalet whose regular swirl is replaced by a stylized zigzag, her H in English with loops at the bottom-left and top-right so that it can be written in a single stroke, making it look almost like a highway interchange.

“With Savyon, her writing was just waiting to be a font,” said Koppel, who also made Kipper’s font. “It’s just a shame that it was this way.”

The project has so far created 10 fonts based on the handwriting of victims, with many more in the works, Marmorstein-Yarhi said.

For now, all of the fonts are in Hebrew and all of the designers are based in Israel, but the project is open to expanding both of those. “It’s dynamic. If we see that there are lone soldiers who wrote in English and theres a need, we’ll consider it,” she said.

Marmorstein-Yarhi stressed that the project is open to all of the victims, not only those with particularly distinct or beautiful handwriting. “Theres no such thing as ‘not pretty’ handwriting,” she said. “Even if someone has totally normal handwriting, its still theirs and something special.”

According to Marmorstein-Yarhi, the fonts have already been downloaded thousands of times, including by some of the country’s top designers but also by average citizens looking to keep the memories of the victims alive.

“We want these fonts to be used, not to just be something for sentimental value,” she said. “A reserve officer told us that hed been writing reports in Salman’s handwriting.”

Initially, Ot.Hayim reached out to the victims’ families to see if they would be interested in having their loved ones’ handwriting turned into a font, but once the project gained some renown through media coverage, people started contacting them.

“Someone from Kibbutz Kfar Aza called us. She asked if there was a limit. We didnt understand what she meant, so she explained that she wanted to do it for five members of her family who were killed in Kfar Aza, but didn’t know if that was too many,” Marmorstein-Yarhi recalled.

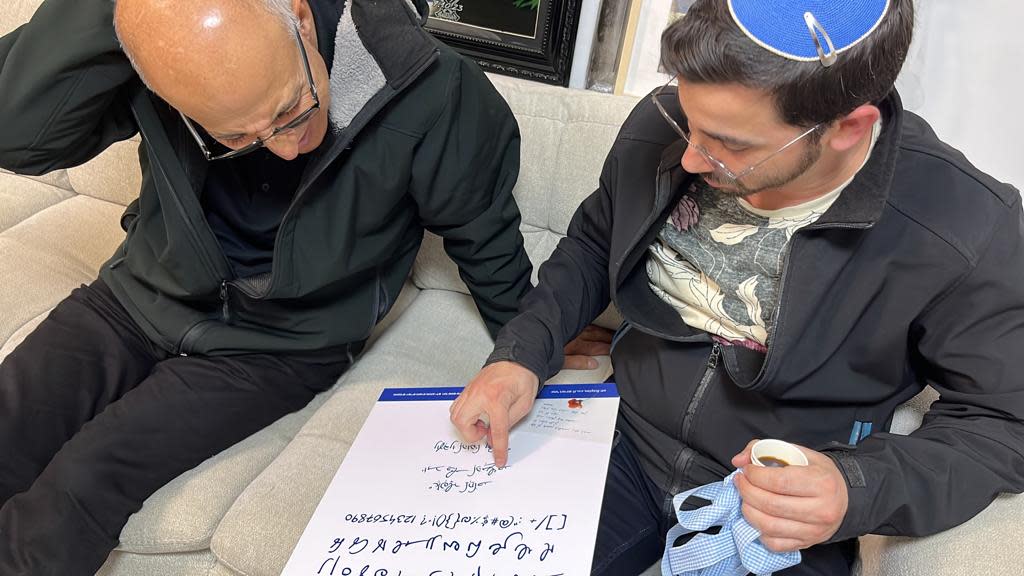

In order to create the fonts, the project first needs handwriting samples from the victims, which they receive from their families.

“We treat these things sensitively, sometimes with tears,” Marmorstein-Yarhi said. “In some cases, [the writing samples] are goodbye letters that soldiers wrote before going into battle.”

The operation currently runs on an exceedingly low budget, Marmorstein-Yarhi said, with everyone involved working in a volunteer capacity. Only designers who already have access to pricy Hebrew font creation software are eligible to take part.

Additional funding would allow the project to potentially purchase the software for itself, which could expand the pool of designers. It would also go to covering the costs of printing framed copies of the fonts that Ot.Hayim gives to both the families and the designers.

Marmorstein-Yarhi said it was important for Ot.Hayim to “include all of the colors of the rainbow of Israeli society [in the project]: a girl who was killed in Kfar Aza [Raviv], and a girl who was killed at the party [Kipper], an officer from a Druze village [Habaka] and a religious Ethiopian soldier [Staff Sgt. Alemnew Emanuel Feleke].”

The designers also represented a diverse array of backgrounds, “from the most international, Tel Avivi people to Haredi designers,” she said. “We are trying to send a message of unity.”