Israel’s founding was complex and messy – but it certainly wasn’t imperialist

The “decolonisation” story is a moral melodrama, performed in stark divisions: black versus white, oppressed versus oppressor, good versus evil. That’s the comic-book source of its recruiting appeal, exciting the desire of mortal humans to plug their little lives into a grander narrative where they play righteous crusaders crushing underfoot unrighteous infidels.

It’s also the spiritual source of the decolonisers’ unscrupulousness. For, what does utter evil deserve except utter destruction? By this reasoning, what do MPs who refuse to vote for an unconditional ceasefire in Gaza deserve except the intimidation of their families and death threats?

The sinister logic was laid bare last October by University of Kent lecturer, Dr Shahd Hammouri, who, the day after Hamas’s atrocious attack on Israel, asserted online that “resistance by the Palestinian people by all means available … is a legitimate act”.

Two months later, on Al Jazeera, she invoked Israel’s “settler colonialism” in justification: “Israel is a colonising power and the Palestinians the colonised indigenous population.”

That’s the simplistic melodrama. Here’s the complicated truth. Before 1914, Jewish corporations bought Palestinian land from Arab landlords to settle thousands of Zionist immigrants fleeing Russian pogroms.

The immigrants preferred building their settlements with fellow Zionists. Accordingly, they let go of Arab tenants they’d inherited. Naturally, the Arabs resented this. Their displacement was legal, but since was bound to excite racial antagonism, it was also tragic. Whatever our evaluation, this was no “invasion”.

In 1917 the British government made the Balfour Declaration, pledging to establish “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, without prejudice to “the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities”. A major motive was sympathy for the Zionist story of an exiled people yearning to return home.

It’s widely believed that the declaration betrayed a promise made in 1915 to Hussein, sharif of Mecca, that Britain would establish an Arab state encompassing Palestine. But there was no betrayal. The British established two Arab states, Jordan and Iraq. And, as Elie Kedourie argued in his book In the Anglo-Arab Labyrinth (1976), they hadn’t promised to include Palestine.

After the First World War, the League of Nations mandated Britain to administer Palestine with the aim of building an independent state and a Jewish homeland out of the ruins of the Ottoman Empire. What kind of “national home” remained undetermined.

During the Mandate’s quarter of a century, the British tried a variety of permutations to satisfy both Jew and Arab – a semi-autonomous Jewish province in an Arab state, a Jewish state in an Arab federation, and a bi-national state. However, they had underestimated the difficulty of constructing a viable polity out of cultures as divergent as those of European Jews and Levantine Arabs.

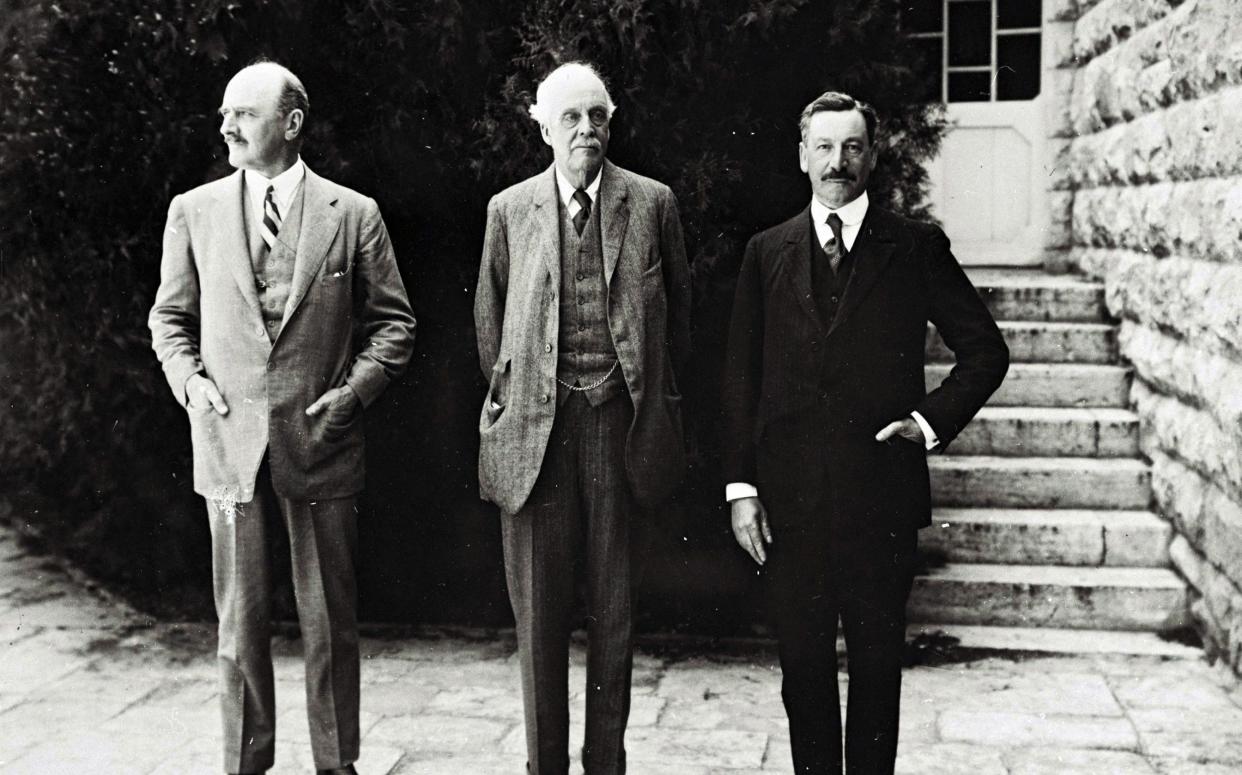

No option proved mutually acceptable. British frustration was memorably expressed by Ronald Storrs, governor of Jerusalem, when he wrote in his 1939 Orientations: “Two hours of Arab grievance drive me into the Synagogue, while after an intensive course of Zionist propaganda I am prepared to embrace Islam.”

Arab frustration had burst into violence in 1920, when the “Nebi Musa” riots left five Jews dead and 216 wounded. Further riots followed, culminating in the Arab Revolt of 1936-9. While the immediate motive was anti-Zionist, it wasn’t untainted by historic anti-Semitism.

One instigator of the 1920 riots, who became the leader of Arab resistance, Haj Amin al-Husseini, ended up in Nazi Germany in 1938, where, as the far-Left Israeli historian Ilan Pappe charitably puts it, he “confused the distinction between Judaism and Zionism”.

Responding to Arab grievances, the British considered restricting Jewish immigration in 1930, but decided against it out of sympathy for Jews fleeing Nazi Germany. When they did impose limits in 1939, the extremist Zionist terrorist group, Lehi, sought an alliance with Hitler to oust them.

Exasperated by their failure to broker a compromise and subject to increasing violence, the British unilaterally withdrew from Palestine in February 1947. In November, the United Nations voted to create two states, one Jewish, the other Arab. At that point, Jews occupied only ten per cent of the territory.

However, when invading Arab armies failed to crush the nascent Israel in 1948-9, some 750,000 Arabs fled Palestine, abandoning their land. Some reckon half were deliberately expelled. Similarly, Arab troops occupying Jerusalem forced Jews out and a further 900,000 were driven from Arab countries, most seeking refuge in Israel.

That’s the whole, messy truth about the founding of the State of Israel. It involved victims and villains on both sides, and a lot of human tragedy. The cartoonish “decolonisation” narrative doesn’t begin to do justice to the past and authorises unrestrained, even genocidal, violence in the present.

So, whether driven by what Kedourie called “the canker of imaginary guilt” or merely by the desire to look good in the eyes of peers, those who are busy “decolonising” our universities, schools, museums, and media need to wake up. They’re spreading poison.

Nigel Biggar is Emeritus Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology at the University of Oxford