Iraq’s Sunni 'war of liberation’

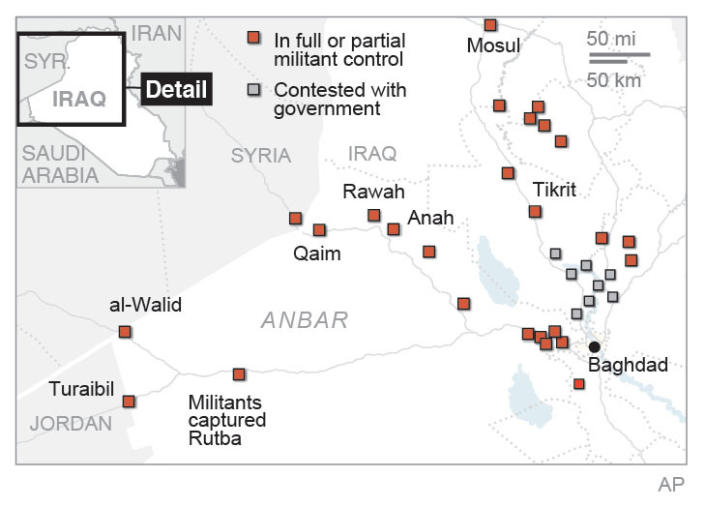

The main force of Islamist extremists apparently slipped from Syria into Iraq a few weeks ago near the Rabia border crossing, taking advantage of a well-worn smuggling route that connects Damascus to the northern Iraqi city of Mosul. Even united with their brethren on the other side of the border, the militants of the terrorist group Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) initially amounted to just several thousand fighters, and yet their plan improbably called for the capture of major cities in northern Iraq stretching from Mosul to Samarra. The success of a terrorist juggernaut that overran four Iraqi army divisions, put much of northern Iraq under militant control, and brought the extremists to the doorstep of Baghdad in a week will go down as one of the most improbable in the annals of military campaigns.

Initially it appeared that whole mechanized army divisions and major cities were falling like dominoes to ragtag convoys of lightly armed militants in pickup trucks. According to a number of Sunni tribal sheiks and former senior Iraqi army officers, however, ISIL [also known as ISIS] militants were the shock troops and staging cells in a long-planned campaign by an alliance that also included disparate Sunni militias and local groups who knew that Iraqi Security Forces' defenses were weak, and essentially threw open the gates to the cities from within in Trojan horse fashion.

“The fall of Fallujah, Mosul, Tikrit, Salah al-Din Province is the direct result of an alliance of different Sunni groups and fighting organizations, to include ISIL, former Iraqi military officers, former Baathists, a new generation of Sunni tribal sheiks, and Sunni resistance groups like the Naqshbandi Army and the 1920s Revolution Brigade,” said a former Iraqi general and Sunni currently living in northern Iraq, who requested anonymity because his life could be in danger if his identity were known. “It seems a deal was reached among all these groups to start a war of liberation in areas of Iraq under control of Sunni governors, and it has been met with unexpected success due to the collapse without a fight of the four army divisions in northern Iraq.”

What initially appeared as an improbable juggernaut by a well-known Sunni terrorist group has thus come into focus as a more general uprising with several key players: Savvy and ruthless ISIL militants who have honed their terrorist craft during the long war against U.S. forces in Iraq and, more recently, during three years of civil war in neighboring Syria; senior Baathist military officers schooled in offensive military operations involving organized formations; a network of armed Sunni tribes and resistance groups who once again have found common cause with Sunni Islamist extremists — all maneuvering in a swamp of Sunni grievance and resentment against a sectarian government in Baghdad.

“The ISIS offensive begs the question of how a terrorist group so quickly developed this new military capacity to plan, prepare and execute a major ground offensive?” said Jessica Lewis, a former U.S. Army intelligence officer and currently director of research at the Institute for the Study of War. Given that the rhetoric now on ISIS’s website has a Baathist ring to it, she said, it’s a reasonable assumption that some former Baathist military commanders have reached an accommodation with ISIS before this campaign. “If a Sunni population that once utterly rejected al-Qaida in Iraq [ISIL’s former name] and its brutal ways now finds conditions inside Iraq so bad that they are willing to fight alongside it, that also suggests it will be extraordinarily hard to find a diplomatic accommodation that brings Sunnis back into the political fold.”

The current offensive began in earnest in January with ISIL’s capture of the strategic crossroads city of Fallujah, a Sunni stronghold where U.S. forces had fought the bloodiest urban battles of the Iraq war. In planting his black flag in Iraqi territory for the first time since U.S. troops withdrew in 2011, ISIL’s astute commander, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, learned two valuable lessons: First, Shiite Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki had so corrupted the leadership of Iraqi Security Forces with cronyism and purges of competent Sunni officers that even its best units were unable to dislodge ISIL from Fallujah despite months of bloody fighting. Maliki has even turned some of the crack ISF Special Forces units in Baghdad into a Praetorian Guard for personal self-protection and political intimidation of his rivals, having them report directly to his office instead of the Ministry of Defense.

Second, al-Baghdadi discovered that the Sunni tribes and numerous armed resistance factions who switched allegiances and found common cause with U.S. forces in 2007 as part of the “Anbar Awakening” felt betrayed by Maliki’s sectarian rule. Once U.S. troops left in 2011 the Baghdad government largely reneged on promises to continue paying salaries to Sunni tribal fighters who turned against al-Qaida in Iraq. Mostly peaceful demonstrations against Maliki in Anbar last year were crushed by Iraqi security forces who killed a number of protesters and imprisoned many more. The Sunni vice president Tariq al-Hashimi, a Maliki rival, was convicted of murder in 2012 and sentenced to death in absentia in a trial most outside observers viewed as political.

As a result of those perceived sectarian slights, some Sunni tribes were once again willing to reconsider a tactical alliance with the Islamist extremists.

“I still have friends among the Sunni tribal leaders in Anbar, and a younger generation is now in open revolt against the more conservative tribal leaders who crafted the ‘Anbar Miracle,’ and against the Maliki government in Baghdad,” said Robert Baer, a former longtime CIA case agent for the Middle East. A number of Sunni tribes have now joined with ISIL and a host of former Baathist officers from Saddam Hussein’s time, he said, in an open Sunni rebellion. “They are also drawing strength from a Sunni population that is pissed off, because I can assure you otherwise it would be physically impossible for a few thousand ISIS shock troops to capture northern Iraq with mostly small arms. I warned my Sunni friends against allying themselves with the likes of ISIL, but they’re not listening anymore. They’re mad, and they’re going to let Allah sort it all out.”

Evidence of that planning and collusion recently emerged in Mosul, where ISIL fighters quickly handed over administration of the city to a General Military Council for Iraqi Revolutionaries, whose spokesman, Muzhir al Qaisi, is a former Iraqi general. He publicly admitted to the BBC that Mosul was too big a city for ISIL to have taken alone. The military council is tasked with operating government facilities and airports and trying to keep banks, hospitals and power stations open.

Hundreds of mid- and high-level al-Qaida commanders and other Sunnis have also been released from northern prisons and, according to U.S. intelligence sources, many have joined ISIL ranks that have now swelled to an estimated 20,000 fighters. That allowed the ISIL militants, many of them foreign fighters, to gain strength as they moved from city to city intent on the next conquest.

The fact that a multigroup General Military Council for Iraqi Revolutionaries is now administering governance in Mosul also helps explain why there have not yet been any popular uprisings by the local populations against ISIL’s typically heavy-handed imposition of a strict version of Sharia law.

“After gaining control of Mosul the armed groups removed all the T-walls [blast barriers] and opened all the streets that had been closed by the Iraqi Security Forces, in order to send the message to the local people that ISIS was there to liberate them,” said the head of a local governing council in northern Iraq.

According to another Sunni tribal sheik in northern Iraq, many locals have indeed embraced the Islamist extremists as liberators. “When ISIL and the armed groups entered the northern cities, they found that people were willing to accept them because all the suffering and humiliation they endured at the hands of the ISF and Baghdad government,” he said. “Innocent people were arrested and imprisoned daily, and all the Sunni families wanted was a return of their loved ones and guarantees that their rights and honor would be guaranteed.”

The various Sunni factions are currently united in their rejection and hatred of Maliki, but their goals are different and likely to diverge at some point. Like its former al-Qaida masters, ISIL wants to establish an Islamist caliphate encompassing Sunni areas of Syria and Iraq and ruled by the dictates of its fundamentalist interpretation of Sharia law. It hopes to provoke Shiite Iran to join the battle by indiscriminately slaughtering Shiite soldiers and bombing Shiite holy places, the better to cement Sunni support in an all-out sectarian civil war. The more secular Sunni groups and leaders, however, hate the Iranians and are disgusted by some of ISIL’s brutal tactics. They seem to see the current offensive as a means of drawing the United States back into the conflict in hopes that Washington will once again use its influence to establish a temporary, transitional government that forces Maliki out of power.

On his current trip to the Middle East to rally Arab support for a solution to the crisis, Secretary of State John Kerry hinted that Washington was considering just such an option, saying in Egypt on Sunday that it was important for Iraqis to “find leadership” that could “represent all of the people of Iraq,” and bridge the country’s deep sectarian divisions. In Baghdad on Monday, Kerry met with Maliki and other Iraqi leaders from all the major sects, pledging U.S. support if they were willing to rise above “sectarian motivations.” At the same time, roughly 300 U.S. special operations forces are deploying to Iraq along with airborne U.S. surveillance, reconnaissance and intelligence platforms to gather information on both the relative strength of the ISIL-led alliance and weakness of Iraqi Security Forces, and to help identify ISIL formations and leaders for possible U.S. airstrikes.

Meanwhile, officials at the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad are nervously monitoring the approach of ISIL forces into the Sunni belt surrounding the capital from three sides, knowing that the Islamist militants and their allies have likely infiltrated Iraqi Security Forces and have captured artillery pieces that can accurately range downtown Baghdad from as far away as 15 miles. No one doubts that the U.S. Embassy would be high on ISIL’s target list. The Obama administration may have only weeks or even days to engineer a political deal that peels off reconcilable Sunni tribes and once again isolates the Islamist extremists of ISIL. A possible alternative no one wants to contemplate is U.S. military helicopters hovering on the roof of an evacuating U.S. Embassy in Baghdad, signaling another historic American defeat.