Inside Yves Saint Laurent's Paris Apartment

Yves Saint Laurent, the Algeria-born French fashion designer who rocked the second half of the 20th century, defined poetic opulence, domestically speaking. Think walls muraled in the manner of Claude Monet’s water lily paintings and bedrooms decorated (AD100 grandee Jacques Grange did the honors) to evoke characters from À la recherche du temps perdu, the swoony Marcel Proust epic that was a Saint Laurent obsession, so much so that he once purchased a country house largely because it had been built by the father of Proust’s publisher. The couturier’s double-height salon in Paris was an Aladdin’s cave, a molasses-dark receptacle for some of the rarest 20th-century furnishings and art. Then there were the Moroccan residences with Arabian Nights decors that, like the apartment in Paris and the manoir in Normandy, exhibited the genius of Grange as well as the Maghrebi-mod stylings of Marrakech architect Bill Willis. Small wonder that Saint Laurent’s estate sale at Christie’s in 2009 set a world record for private collections at auction, bringing in nearly $500 million, all of which went to various charities.

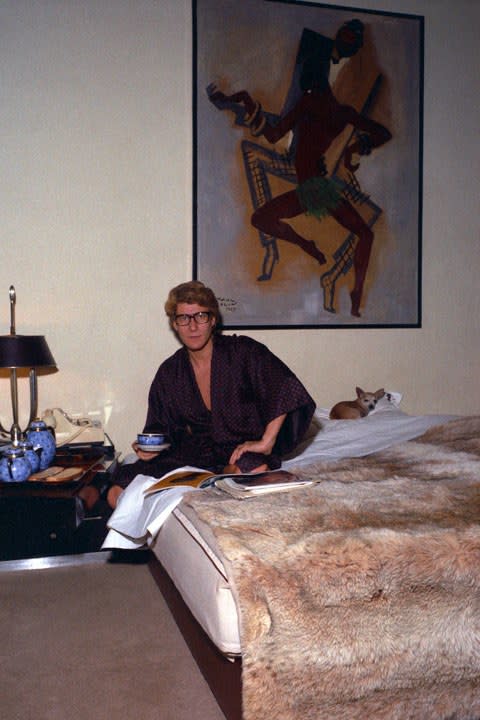

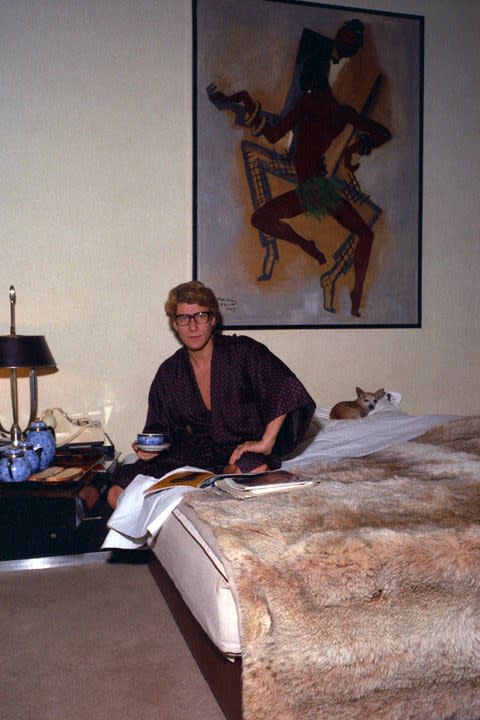

Yves Saint Laurent in Bed

"For somebody like me, who can’t stop accumulating objects," Saint Laurent told AD editor at large Charlotte Aillaud for an 1988 article about the Paris apartment, "the absence of them is an oddity." He’d have been more truthful if he’d actually said “has become an oddity.” Earlier Saint Laurent spaces seem relatively uncluttered, but that clarity was largely swept away when the preternaturally talented pied-noir succumbed to a lust for objects once his fortune had been made. (Expanding into ready-to-wear beefed up his budget, as did the earthshaking 1977 launch of Opium, his “lush, heavy, and languid” parfum, which brought in $30 million in one year alone.) One of those early interiors was the original dining room at 55 rue de Babylone in Paris, the large duplex apartment that he and his lover Pierre Bergé—steel-trap business partner, ardent Socialist, publisher, patron of the arts, AIDS activist, philanthropist, newspaper investor, and, finally, just days before Saint Laurent died in 2008, civil spouse—began renting in 1970 and purchased eight years later.

Designed in the 1890s by architect Leon-Pierre Saulier, 55 rue de Babylone “is not grand in appearance. It is not an hôtel particulier,” Paris art dealer Robert Murphy wrote in The Private World of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé (Vendome, $95). “It is what the French call an immeuble de rapport, a bourgeois building typically constructed by aristocratic families to augment income.” Still, it turned out to be an appropriate nest for the fashion-world power couple, since the man who built it and had lived next door, Baron Denys Cochin, was an omnivorous aesthete, too. “In art, M. Cochin walks from end to end,” marveled one contemporary of the government minister, writer, and collector. “This Parisian of great taste goes from Manet to Bouguereau without ever getting bored.”

After Saint Laurent and Bergé settled in, Vogue produced a feature in its November 1971 issue, with photographs by Horst P. Horst. The apartment’s suavely oak-paneled salon (reputed to be a Jean-Michel Frank remodel from the 1930s, though that’s never been proven) was already beginning to exhibit hints of the magpie connoisseurship that would eventually engulf it. That was fueled in large part by Saint Laurent’s shopping spree at Drouot the following year, when the Art Deco treasures amassed by the Belle Époque fashion darling Jacques Doucet came on the market. The nearby dining room, on the other hand, still suggested the laid-back domesticity of his and Bergé’s first decade together. (The men met in 1958, at a dinner party, and ended their fraught romance in 1976 but they remained symbiotically, complicatedly intertwined for life.)

With two tall casement windows that overlooked a green-on-green garden where Asian box turtles lumbered, the rue de Babylone dining room was uncomplicated yet snappy. The walls shone with a high-gloss paint that Vogue rapturously called “freesia-white,” and the floor was obscured beneath a pile carpet the color of snow. Furnishings were few, and most of those were recycled from Saint Laurent and Berge’s former home at 3 place Vauban, a 19th-century garden apartment that they rented from its owners, the duc and duchesse de Sabran. The white-on-white library on rue de Babylone’s lower level, adjacent to what was then Saint Laurent’s bedroom, reused some furnishings, too, in an upgraded re-creation—subtly enriched over the years by Grange—of place Vauban’s salon, right down to the iconic YSL bar by François-Xavier Lalanne (Carla Fendi snapped it up at Christie’s for about $3.5 million) and shelves full of books, photographs, and humble mementos that Saint Laurent charmingly described as “simple barefoot things.”

In the rue de Babylone dining room, reproduction Louis XV side chairs, as white and slick as the walls, surrounded a white Saarinen Tulip table by Knoll. The latter, in turn, was topped by a disc of Carrara marble. “I like to eat fast around a round table,” Saint Laurent explained, “so I can see everyone I am talking to and we have a feeling of closeness.” Chromatic relief came from the greenery beyond the windows, two 17th-century Chinese covered jars set on attenuated metal consoles, and the blue-and-white china plates that Saint Laurent combined with heavy old-fashioned silver, porcelain-handled knives, and hearty goblets of the sort that could have been used at Château de Versailles, but back when it was Louis XIII’s hunting lodge rather than Louis XIV’s palace.

By the time Christie’s auctioned the apartment’s contents in what every newspaper, magazine, and website (AD’s included) hailed as “the sale of the century,” that round dining table, as well as the room’s invigorating snap, had vanished. What had been spare and sunny had become practically papal. A photograph of Saint Laurent, snapped the day before his final show in 2002, captures him waiting for luncheon to be served, seated in an 18th-century Italian Rococo giltwood chair that would not look out of place at the Vatican. (Previous owners of the chair and its 14 mates included the Bolivian tin magnate Anteñor Patino and American robber baron William Whitney, who purchased them from Stanford White, his architect and decorator. White bought them in the 1890s from the princely Genoese family that commissioned them in the 1740s.) In front of the fashion designer is a hulking rectangular beige-marble table, its silvered base bringing to mind New York’s Chrysler Building; behind him stretches Le roi porté par deux maures, an early-18th-century Gobelins tapestry depicting a Brazilian Indian king being carried through a jungle by African slaves. Pine-green damask cloaks the formerly bare windows, narrowing the apertures for natural light, and the formerly snowy floor has been paved with highly reflective black marble.

AB - Yves Saint Laurent

Fittingly enough, given the grand seigneur that haute couture’s freshest face had become—complete with a buttonhole aglow with the red threads of the Légion d’Honneur—the atmosphere was imperious and deeply rich. Yet a touch of the old days remained. The simple goblet set before Saint Laurent is from the same set pictured in Vogue more than 30 years before. The Chinese covered jars remained, too, but since every available surface was too crowded to display them, they had migrated to the floor, almost unnoticed amid the splendor.