Improved Animal Crossings Show a Huge Decline in Wildlife Collisions

From the August 2018 issue

Roads cover less than 1 percent of the land in the United States, but their effects extend beyond their edges, disrupting the habitats and movement of many animal species. So, yes, Crossy Road may be just a Frogger rip-off, but it’s also based on real life. Acknowledging that we’re not going to stop building roads or driving on them, ecologists and government officials have embraced wildlife crossings.

Though costly compared with highway warning signs and reflectors, crossings are the most successful roadkill remediation tactic. A 2016 study has shown that properly implemented crossing structures led to an 83 percent reduction in large-mammal roadkill. A recent $46 million project in Colorado did even better. While rebuilding an 11-mile section of State Highway 9, Colorado allocated $12 million of the budget for two wildlife overpasses and five underpasses, and its department of transportation has reported a 90 percent drop in wildlife collisions in the area since completion.

Location is key here. Just as you won’t trek half a block to use a crosswalk, animals cross roads where it is most convenient. But there’s more to site selection than just situating crossings in areas with the densest roadkill. Crossings are most effective when they link habitats for the specific species they are designed to protect. Here’s a look at the various types of crossings and why they work:

// Bridges over Babylon

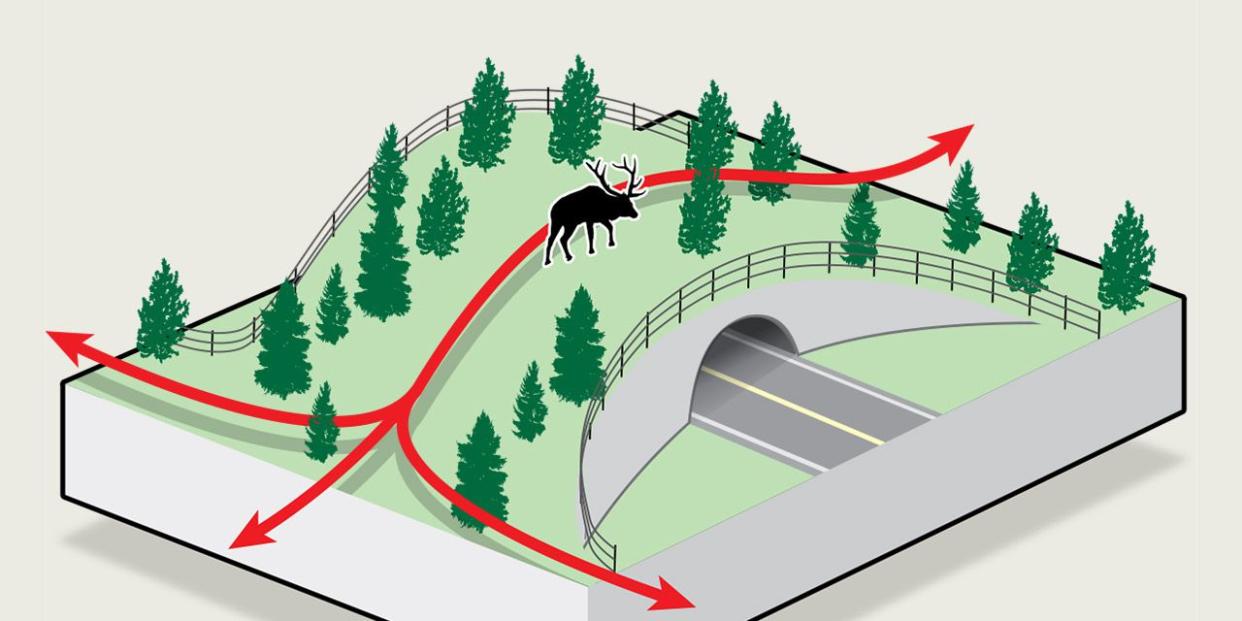

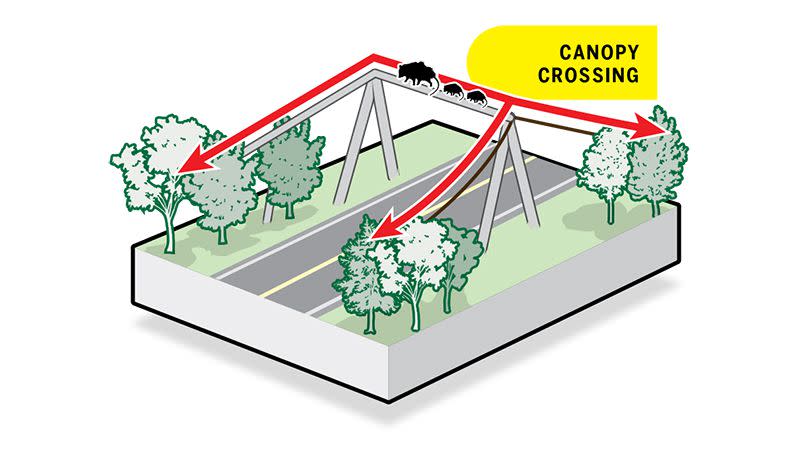

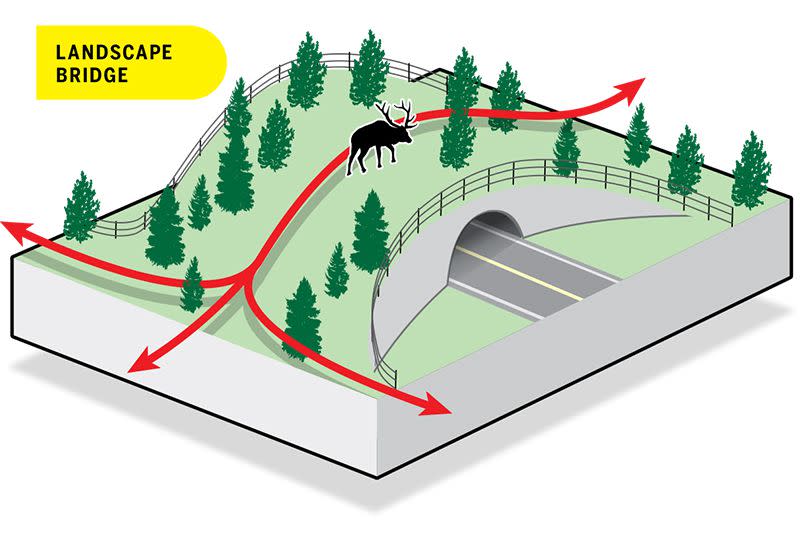

The largest crossing structures are the landscape bridges and overpasses, which can be the size of a football field. Ideally, these structures rise seamlessly from the surrounding areas and incorporate berms on their sides to hide the road below. Landscaping mimics adjacent habitats through the use of trees, rocks, dense cover for smaller creatures, and even small ponds for amphibians. For maximum effectiveness, these crossings are off-limits to humans or designed to segregate the human pathways. Overpasses are used by most animals, including deer, coyotes, and other small mammals; some animals, such as moose, will steer clear if the structures are not wide enough or if they’re also used by people. In areas with semi-arboreal species, such as squirrels and raccoons, canopy crossings made of ropes and platforms connected to trees or signage can help the little critters get out of harm’s way.

// The Over-Under

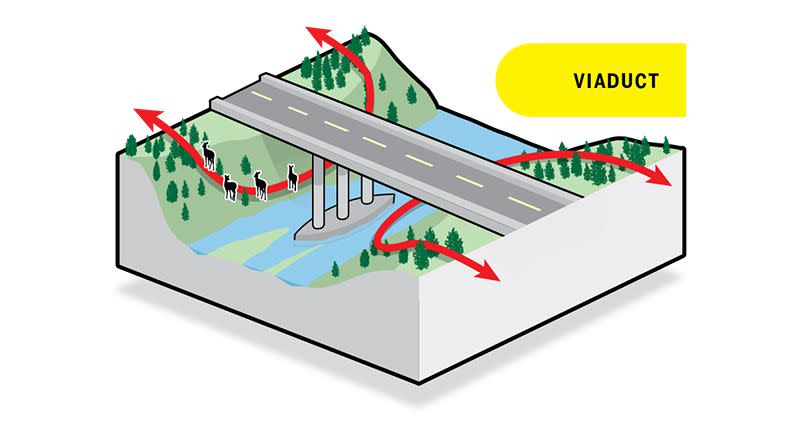

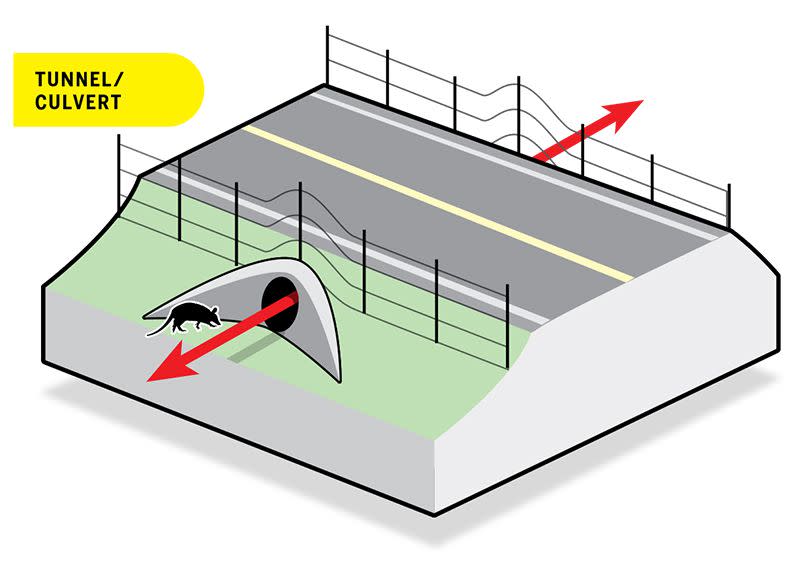

Underpasses can take multiple forms, from wide viaducts that span wetlands to simple culverts and even specialized tunnels for amphibians and reptiles. As with overpasses, underpasses work best when the ground is landscaped and the passageway includes a variety of features to provide cover. Good drainage is essential to avoid flooding. Culverts and other narrow underpasses are especially attractive to smaller animals, as these passageways limit predator access.

// Fenced Out

Wildlife crossings work best when animals are guided toward them with fencing or walls. The former often employs mesh of varying sizes and heights to control which species get in and which stay out. But fencing itself is vulnerable, susceptible to being knocked down by weather or cars, and animals have a knack for finding a hole in any fence. When animals wish to exit a fenced area, gates and “jump-outs”-mounded dirt on the inside of the fence that animals climb to reach the top of the barrier-permit safe escape.

('You Might Also Like',)