Imprisoned Doctors Who Resisted the Nazis at Buchenwald Inspire Us Now

In January 1944, when a group of 5,500 French prisoners arrived at Buchenwald concentration camp outside Weimar, Germany, among them were a dozen doctors, arrested and deported for resistance activity in occupied France. Some were assigned initially to grueling work in the stone quarry or digging tunnels for an underground rocket assembly plant, but it wasn’t long before the camp’s clandestine resistance group got them moved into medical service in the camp clinics. They would help carry out the group’s declared goal of defeating the Nazi extermination project: to survive, and to keep as many prisoners alive as possible.

The Man Who Enabled the Holocaust

Because of the coronavirus pandemic, commemorations of the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Buchenwald, originally set for April 5-11, have been cancelled. Yet the moment brings more reason than ever to examine the role played by doctors and the organized resistance of prisoners, thrown into catastrophic conditions with few resources at hand. Working together and for the greater good made the difference between life and death not only for their patients, but for the doctors themselves.

Buchenwald, a slave-labor camp of slow extermination, had two clinics, one in the Big Camp section and one in the Little Camp section. Both were key elements in the secret resistance.

The group had been formed from the camp’s opening in 1937, when German communists and anti-fascists imprisoned there organized to defend themselves against the harshest measures of the SS administration. Other nationalities were brought in as the prisoner population expanded, but the senior members in charge remained the early German arrivals. For example, prisoner Ernst Busse, a former Reichstag deputy from the German Communist Party, held a position as administrator of the Big Camp clinic, overseen by SS medical officers.

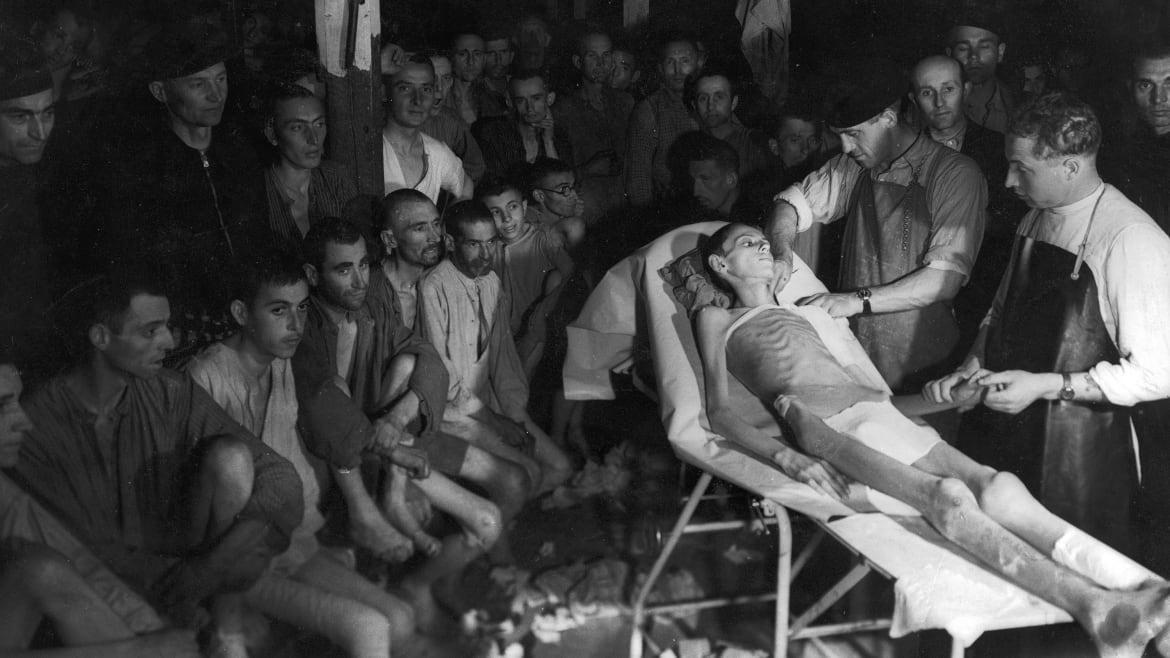

Four Czech doctor-prisoners constituted the only medical service when the first French doctor, dermatologist Jean Rousset, arrived in late 1942. He was joined in fall 1943 by Dr. Jacques Brau, a radiologist who was horrified to find random prisoners performing surgery. At Big Camp clinic, the “chief surgeon” was a mason by trade, while at Little Camp, the “chief surgeon” was a shoemaker. When the larger group of French doctors arrived in 1944, these longtime prisoners did not give up their command over the clinics, but the doctors were able to take the upper hand in surgery, most of the time.

At first, there was one cell block for medical treatment. The first camp commander, Karl-Otto Koch, was quoted by the early prisoners as saying: “In my camp, there are no ill people. Here people are well, or they are dead.” Koch was transferred to a subcamp in 1941, after his corruption and abuse of prisoners became too much even for the SS, who then executed him in April 1945.

The second camp commander, Hermann Pister, was charged with war crimes in 1947 and sentenced to death, but died of a heart attack while still in prison. Pister’s medical commander in the camp was Dr. Gerhard Schiedlausky, who had begun sadistic surgical experiments on women prisoners at Ravensbrück camp before being transferred in October 1943 to Buchenwald, where he continued his macabre work. Many of the experiments there concerned finding a vaccine for typhus, a deadly bacterial disease spread by lice.

The SS doctors made rounds in the clinics, but left day-to-day care to the French and Czech doctors and their kapo overseers. Dr. Victor Dupont, a co-founder of Vengeance, one of the largest resistance groups in France, was among the January arrivals. Initially dispatched to a digging detail, Dupont was soon called to an interview by Busse and the clandestine camp resistance about his anti-Nazi actions and his political views. As for his medical skills, the most important question he had to answer was whether he would be able to choose who got treatment and who did not, as there was never enough medicine or material for all the patients. They asked: “If there is only one aspirin, you cannot cut it in two, to whom do you give it?”

The doctors did manage to expand the medical facilities, so that by 1945 the Big Camp clinic stretched over six cell blocks and included a dental service, pharmacy, laboratory, operating room and pathology lab. The Little Camp clinic, originally set up as a facility to quarantine incoming prisoners, was far smaller and more crowded. While a total of 265,980 prisoners came through Buchenwald between 1937 and 1945, the average population in autumn 1943 was just over 20,000. It more than doubled within a year, and then peaked at 110,000 prisoners (including sub-camps) in early 1945. Conditions were so overcrowded and pestilent that winter that an estimated 15,000 prisoners died. Overall, a total of 56,000 prisoners died at Buchenwald.

When Dr. Brau arrived, only an SS officer could decide whether or not a patient would be admitted to the clinic—a life-or-death call that the SS based solely on whether or not the prisoner had a high fever. Brau managed to take over admissions, conducting an interview and diagnosis before deciding whether to let a prisoner stay.

Like the camp, the clinics were overcrowded from 1944 onward, with two to four patients per 60-centimeter bunk, and others lying in hay on the stone floor. The only medications the doctors had occasional access to were aspirin, kaolin and charcoal for dysentery —not even sulfamides for infection. Yet for many patients, simply being able to rest in the clinic instead of enduring a 10-12 hour workday, followed by standing for a 3-4 hour roll call, was healing enough. The clinic also offered more food than they would normally be allotted. Thus a ticket to stay in the clinic could also be a means of survival.

To alleviate the overcrowding, the prisoners’ committees persuaded the camp administration to allow one doctor per cell block, so that patients who needed help could receive it in their block rather than going to the clinic. And rather than crowd all the diseases and conditions into the same ward, they designated one block for tuberculosis, one for dysentery, another for typhus. Dr. Dupont took over the tuberculosis ward, which was particularly suited for hiding prisoners under threat, as the German guards were fearful of contagion.

The clinics also played a political role. Prisoners used them as communications centers for passing messages to their clandestine committees. Prisoners sent to one of the 22 “kommandos”—smaller work camps set up around the region—returned to Buchenwald for medical visits with valuable information about activity outside the camp. And prisoners slated to be executed sometimes could be hidden, especially in the tuberculosis ward. In one incident, doctors hid a Russian prisoner due to be executed, faked his death and presented a certificate of cremation, while helping him escape from the camp.

When the French résistants first arrived at Buchenwald, they hit a wall of resentment and anger from an unexpected source: the other prisoners. The then-majority of Russian and Polish prisoners, along with the German communists, had expected France, a long-known friend of liberty, to fight and defeat the Nazis, and instead it had collapsed into surrender, occupation and in many cases, collaboration.

“[The French prisoners] carried the weight of all the mistakes committed in international politics, errors that brought great disappointment to men who expected the French, as was their habit, to run to fight for their freedom,” wrote Frédéric-Henri Manhès, a former book editor, military base commander and key résistant operative in his postwar account Buchenwald: L’Organisation et L’Action Clandestine des Déportés Français 1944-1945.

Manhès had been arrested in March 1943, just after meeting with Charles de Gaulle at his London opposition headquarters, and was deported to Buchenwald in January 1944. His work as a résistant had been by the side of Jean Moulin, pulling disparate groups into a National Council of Resistance, no easy task in the fractious field of French opposition.

When Manhès, 54, arrived at Buchenwald, he picked up his previous task, this time trying to organize the prisoners into a defensive resistance. He wrote that he could see that survival would be impossible if the French did not stick together. They represented at most 13 percent of the total prisoners, who along with Russians and Poles, included Jews, Roma, homosexuals, and antifascists. Some had been arrested for their identity, others for political action, but the largest group by far were common criminals, turned particularly brutal by their rough incarceration, according to Manhès. They viewed the French résistants—many of them intellectuals and professionals—as easy pickings.

Manhès saw the need for allies, and saw an opportunity in early 1944, when a group of Russian prisoners were punished for an infraction by being deprived of their bread ration for six days. Manhès persuaded the French and others to pool together some bread from each of their rations—estimated at 500 grams per day—and give it to the Russians. It was a small gesture, yet with large consequences of saving lives and creating goodwill. And it showed the prisoners that if they could count on each other, they might survive. This led in June 1944 to the creation of the French Interests Committee, which worked in conjunction with the international resistance, but particularly watched out for French prisoners.

“The French had been beaten, robbed, mistreated, without the ability to raise a voice or protest in any sort of manner,” Karl Madiot, a French notary imprisoned at Buchenwald from September 1943, wrote in a postwar letter. “A good many comrades returned who, without the benefit of that organization, would never have seen France again.”

Dr. Brau also noted in a postwar letter that prior to the committee’s organization, Russians and Poles had stolen any arriving Red Cross packages, and the French had gotten none. Afterwards, they “were able to reserve a small part of the Red Cross packages for the ill or convalescent in the Clinic.”

The camp’s medical service, by then counting some 30 doctors, showed its skill and stamina after the devastating Aug. 24, 1944, bombing of the camp. The U.S. Army Air Corps’ 613th Squadron bombed the Gustloff weapons factory, the DAW electronics factory, the SS barracks and a small wood where prisoners had gone to shelter, killing 500 and wounding more than 1,400 SS guards and prisoners.

The international committee whipped into action, setting up stretcher relays to bring the injured to the clinics and the SS hospital, and a team of French prisoner-surgeons operated in nonstop shifts for 10 days on both prisoners and guards alike. Dr. Pierre Maynadier said afterward that he had operated on 2,000 patients in that chaotic aftermath. The confusion also allowed the military side of the resistance committee to steal weapons from dead SS guards and hide them away.

Those guns came into play eight months later, in early April 1945, as American troops approached Weimar and the camp and the SS officers began to flee. At 1500 hours on April 11, two prisoner companies of the international clandestine army, bearing their stolen guns, took over the guard tower and spread out towards the western edge of the camp, where SS snipers had dug in to defend against the Americans.

The prisoners took the snipers out, and then continued into the forest to check if any other guards were on the run. Instead, they encountered members of the U.S. Third Army’s 6th Armored Division, wondering at the sight of armed men in striped pajamas. They explained, and the Americans shook their hands and gave out cigarettes. They returned to the camp, where prisoners were overcome with joy at their liberation.

In his book, Manhès described the reaction of those who had spent the past 15 months in the hell of Buchenwald, and particularly the German prisoners, some there as long as eight years, who simply broke down in tears. It was over, and they had survived. Manhès wrote that they stood overwhelmed with emotion before their American liberators. “We just had one word to say: Merci.”

Historian Ellen Hampton is currently working on a book with the working title Doctors at War: Clandestine Care under the Nazi Occupation of France. This article is based on research for a chapter on doctors deported to Buchenwald.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.