Imagining a greener world, Indiana University South Bend students measure CO₂ levels

SOUTH BEND — Come spring, the main drag of Indiana University South Bend's campus is one of the more verdant stretches of town. Walking paths wind through blossoming bushes and trees. Rain showers imbue sprawling lawns with a deep green.

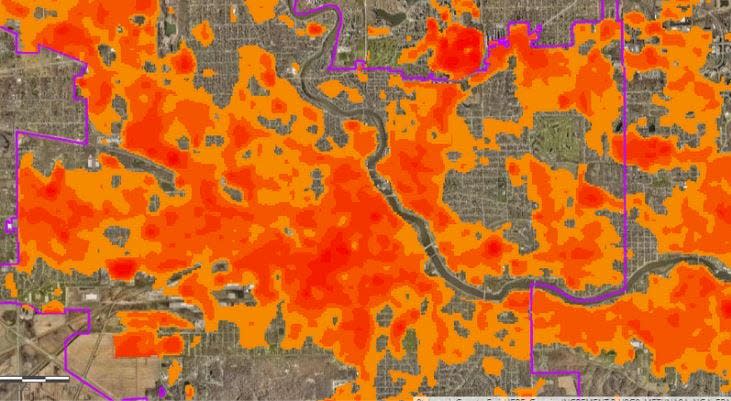

But students in professor Deborah Marr's ecology course are collecting data on problems targeted by the city of South Bend in landscapes where parking lots and pavement dominate. When that's the case, research finds, an area contains higher levels of carbon dioxide and heats up more severely on sunny days. In South Bend, swaths of post-industrial land on the west side experience the worst effects.

Marr is one of several professors advising the city on its plans to achieve a 40% urban tree canopy across South Bend by 2050.

Starting from an average canopy of 26% in 2019, according to city data, that goal will require city government and residents to plant nearly 95,000 new trees and between 30,000 and 60,000 additional trees to replace dying ones. Along with encouraging residents to plant trees, the city will match donations up to $50,000 to its urban tree canopy initiative.

"We have two major complex problems," Marr said. "One is climate change. The other is biodiversity. One of the things that we really need to do is rethink our urban landscapes."

Environment: Knute Rockne's first home will move, as South Bend seeks amends for botched 'tree butchering'

On a mild Wednesday morning, Marr gathered outside with students and distributed small sensors to several groups of them. Created by IUSB's Department of Physics and Astronomy, the sensors will gather data on CO₂ levels in different areas of campus this spring and summer.

Measurements from last fall showed that even small interventions can help to reduce CO₂ levels, Marr said. Sensors detected lower amounts of the greenhouse gas in parking lot islands covered with grass than in similar islands filled with gravel.

"Lots of people will have their cars running for a long time sitting in parking lots, so all that CO₂ just builds up," said Tori Hartl, a senior at IUSB who collected the data with peers Carlee Munson and Darci Lindhe. "So if you have grass or plants or something there, it will help to reduce the impact."

Zach Shrank, a sociology professor who leads IUSB's Center for a Sustainable Future, said he and his colleagues are advising city government on how to bolster the urban tree canopy while achieving the desired environmental and social impacts.

Trees provide overt environmental benefits by filtering storm water and cleaning the air. They dampen city noise and cool down neighborhoods, thereby lowering air conditioning needs in the summer. And a broad review of environmental studies found that urban forests are connected to better public health and well-being. People exposed to wooded areas were found to feel less anxious, less depressed and less fatigued.

But many private residents might view trees as an added burden, Shrank said. They're expensive to plant and maintain. A falling limb is always a liability. Roots breaking up portions of the sidewalk are a nuisance.

"We're interesting in thinking about, if we're going to plant 10,000 new trees in the first five years," Shrank said, "and then maybe another 100,000 trees in the next 30 years ... what are some of the obstacles?"

Marr has taught at IUSB for more than two decades. She said that 50 years from now, the kind of ecologically sparse landscapes common across South Bend and other cities are likely to look old-fashioned.

While there are now about 176,000 trees in South Bend, a 40% canopy calls for more than 270,000. Marr expects the change to be especially visible in disadvantaged neighborhoods, where the average canopy falls below 20%.

She expects a dramatic shift in local landscaping from imported ornamental plants to native species . Native plants support more insects, Marr said, and that biodiversity travels up the food chain to support more birds and other animals. She's also researching how the city can make use of healthier soils to reduce carbon emissions.

"If we think about just little things like parking lot islands, including more native plants, allow them to grow a little bit taller than grasses," Marr said, "those little things can make a difference."

Email South Bend Tribune city reporter Jordan Smith at JTsmith@gannett.com. Follow him on X: @jordantsmith09

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: Indiana University South Bend students measure carbon dioxide on campus