Hustlers, grifters and greed: How Jam Master Jay met his tragic end

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

One evening in the late 1980s, Carlis Thompson showed up at a New York City apartment owned by his cousin, the pioneering DJ Jam Master Jay of Run-DMC.

The group had a show that night, but when Thompson walked into the apartment, he wasn’t greeted by Jay, Joseph “Run” Simmons or Darryl “D.M.C.” McDaniels. The men hanging out were strangers to Thompson, and they instantly rubbed him the wrong way.

“You could tell they were grifters,” said Thompson, who would go on to become a warden at the Rikers Island jail complex.

Thompson walked into the bedroom and embraced his cousin, who was born Jason Mizell. They caught up for a bit, Thompson said, and then it was time to head to the club.

“I’ll never forget it,” he said. “Jason pulled out an Uzi from a closet.”

Thompson was stunned — and alarmed.

“Cuz, are we going to a concert or are we going to war?” he asked.

“You never know,” Mizell replied, according to Thompson.

The exchange proved prophetic. Mizell was shot dead inside his recording studio in Queens in 2002, a killing that stunned the hip-hop world and went unsolved for nearly two decades.

Last week, two men from Mizell’s old neighborhood were convicted in the slaying after a trial that laid bare the difficult predicament he found himself in prior to the murder.

With Run-DMC’s popularity fading, large paydays became more elusive for Mizell, who was known for showering cash on his family, friends and even acquaintances from his old haunts in Hollis, Queens. So he leveraged his old contacts from the neighborhood to carry out drug deals, according to courtroom testimony, a decision that ultimately led to his killing.

For some of those who had known Mizell the longest, the convictions were bittersweet. In the days since the trial, they have wondered how differently his life could have played out had he managed to leave behind the hustlers and hangers-on from his past.

“That was my cousin’s downfall,” said Ryan “Doc” Thompson, who grew up with Mizell and was among his closest confidants. “It was just too late to wash his hands of these people.”

Wendell Fite, a childhood friend of Mizell’s better known by his stage name DJ Hurricane, offered a similar take.

“Jay was the kind of person who thought he could help anybody no matter who that person was,” he said. “Jay always had a big heart, which is why he’s not here today, because he surrounded himself with the wrong people.”

Family ties

Mizell grew up on 203rd Street, one of three siblings whose mother was a schoolteacher and father was a social worker. As a kid, Mizell didn’t have to go far to visit one of his closest friends, a boy who came to be known as Darren “Big D” Jordan.

“He lived directly across the street,” Ryan Thompson said.

The two went way back. Their mothers were best friends who had attended the same church in Brooklyn. The Mizells moved to Hollis, a middle-class neighborhood at the time, to provide a better environment for their children.

Mizell fell in with a group of kids who were burglarizing homes and he served time in juvenile detention. When he got out, he focused his attention on his turntables and went on to become a founding member of Run-DMC.

But he remained tight with his old neighborhood pals. So after Jordan’s son, Karl “Little D” Jordan Jr., was born in 1984, it was no surprise that Mizell became like a godfather figure to him.

“That’s how close these two families were growing up,” Ryan Thompson said.

But that was then. In an almost Shakespearean twist, Jordan Jr. was one of the two men convicted in Mizell’s murder.

The then-18-year-old fired a bullet into Mizell’s head from inches away, a witness told the jury, in what prosecutors described as an act of revenge for being cut out of a lucrative cocaine deal.

“It was an ambush, an execution,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Miranda Gonzalez told the jury in her opening remarks, “motivated by greed and revenge.”

Jordan had long been implicated in the killing, but his arrest in 2020 still came as a surprise to some of Mizell’s relatives.

“He had looked up to Jay,” Ryan Thompson said. “Before he got gangster, he was a nice little kid who respected his elders.”

Prosecutors said in court papers that by the time of his arrest Jordan, an aspiring rapper, had been selling drugs for several years.

That a member of the Jordan family was involved in the murder was especially hard to fathom, some people close to Mizell said, because of the lengths he had gone to help them. The renowned DJ had secured Jordan Jr.’s father a job at Russell Simmons’ artist management company in the late 1980s.

“Jay literally pulled Big D out of the streets,” said an industry source who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation.

Mizell had also done favors for the second man convicted in the shooting, Ronald “Tinard” Washington.

Prosecutors said Washington was a career criminal who had been in and out of prison for much of his adult life. He served time on drug, gun and assault convictions.

“He was a street thug, a tough guy,” a former NYPD detective who worked on the case in 2002 said in an interview after Washington’s arrest.

But Mizell never turned his back on the man. In the days before the killing, Washington was sleeping on a couch at Mizell’s childhood home, where his sister resided, according to courtroom testimony.

A familiar conundrum

Run-DMC released its sixth album, “Down With the King,” in 1993. It would be the group’s last to break into the top of the pop charts.

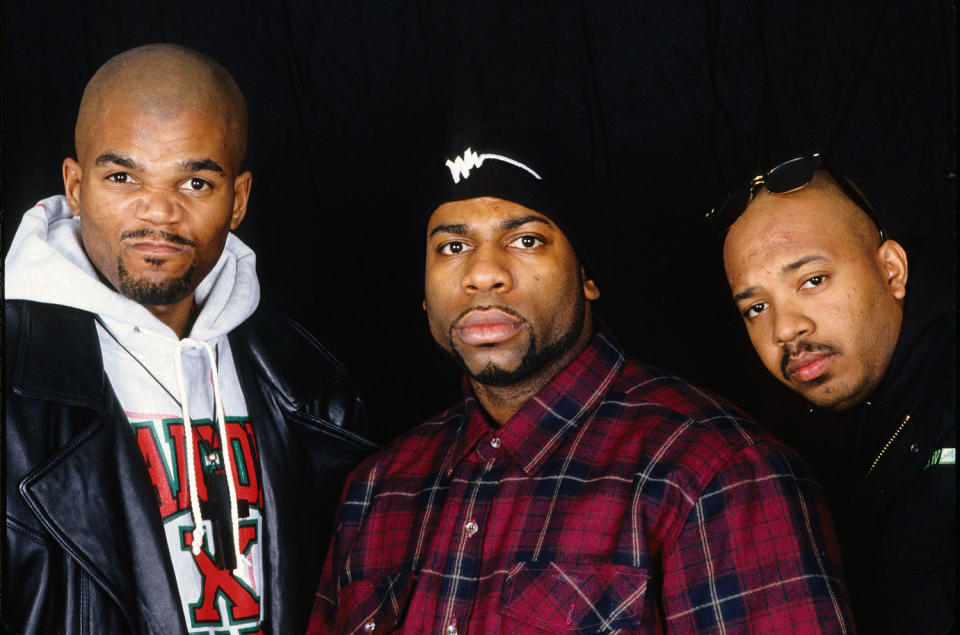

Run-DMC had blazed a trail for other rappers, bringing a sound (spare beats and socially conscious lyrics delivered with bravado) and style (black hats, Adidas jumpsuits, sneakers without laces) that made them famous around the world.

But the 1990s ushered in a sharper-edged brand of hip-hop, with the likes of Ice-T and Dr. Dre rapping about the grim realities in urban centers and the gangster lifestyle.

The members of Run-DMC faced a conundrum familiar to celebrities who attained fame and fortune only to see it slip away later in life: Now what?

Mizell launched his own label, JMJ Records, and saw immediate success with one of his first groups, Onyx. But the company sputtered and some of the people surrounding Mizell didn’t have his best interests at heart, according to family members and industry veterans.

That he turned to drugs to make ends meet, acting as a middleman in occasional cocaine deals, was shocking to many who had known him well.

“It’s kind of jaw-dropping to me and terribly sad,” said Bill Adler, Run-DMC’s longtime publicist. “He’d earned a reputation for himself as a very, very generous guy. When his ability to maintain that reputation began to slip, I think he felt forced to look for other ways to support himself.”

DJ Hurricane said he sees it a bit differently. He thinks that Mizell’s drug activities came less out of financial necessity than out of the company he kept.

“Jay wasn’t a drug dealer. That’s for sure,” Hurricane said. “If anything, he knew somebody that needed something and he knew somebody that had the thing that person needed.”

“It’s easy to get involved in something like this,” he added. “It’s just being around the wrong people.”

Carlis Thompson said that after the Uzi incident, he steered clear of his cousin’s Hollis crew because he didn’t want to jeopardize his career in New York City’s correctional system.

But at family functions, Thompson did urge Mizell to take better care of his money — to invest in real estate or open up a clothing store to capitalize on the Run-DMC brand.

Thompson made a point to attend the murder trial. Following the guilty verdicts, he said he felt like he “could breathe again.”

But he couldn’t stop thinking about Mizell’s other family members — his mother Connie, brother Marvin and sister Bonita.

As the years passed with no arrests in the murder, they had pleaded for witnesses and anyone else who knew something to come forward. But they never got any justice.

One by one, his family members all died in the years before Jordan and Washington were arrested.

“His mother was the last one that we buried,” Thompson said. “At that time, we didn’t have any arrests.”

“I try not to think about it,” Thompson added, “because it breaks my heart.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com