Hurricane-ravaged Immokalee can always count on Edgerrin James

IMMOKALEE, Fla. – The coach kept talking about food. Had the players eaten? Did he have enough to feed them? How many peanut butter and jelly sandwiches could be made before practice?

“It’s a huge issue,” said Rodelin Anthony, the football coach at Immokalee High. “My kids don’t know where their next meal is coming from. Some still don’t have power. Ice is a rare item. Everyone in the town needs ice.”

This was a week after Hurricane Irma tore through this rural region of southwestern Florida, and finding food had become the new obsession for a 30-year-old coach. It was poignant and ironic; this is the region where most of America gets its winter tomatoes.

Many folks in cities near the Gulf Coast are figuring out how to recover from Irma. In Immokalee, many don’t have insurance and more than half the residents in this town live below the poverty line. Anthony guesses about half of his players had homes that were either severely damaged or wrecked altogether.

“A majority of kids are from migrant families,” Anthony said. “A handful are migrant kids. They won’t tell you outright. But you know who they are.”

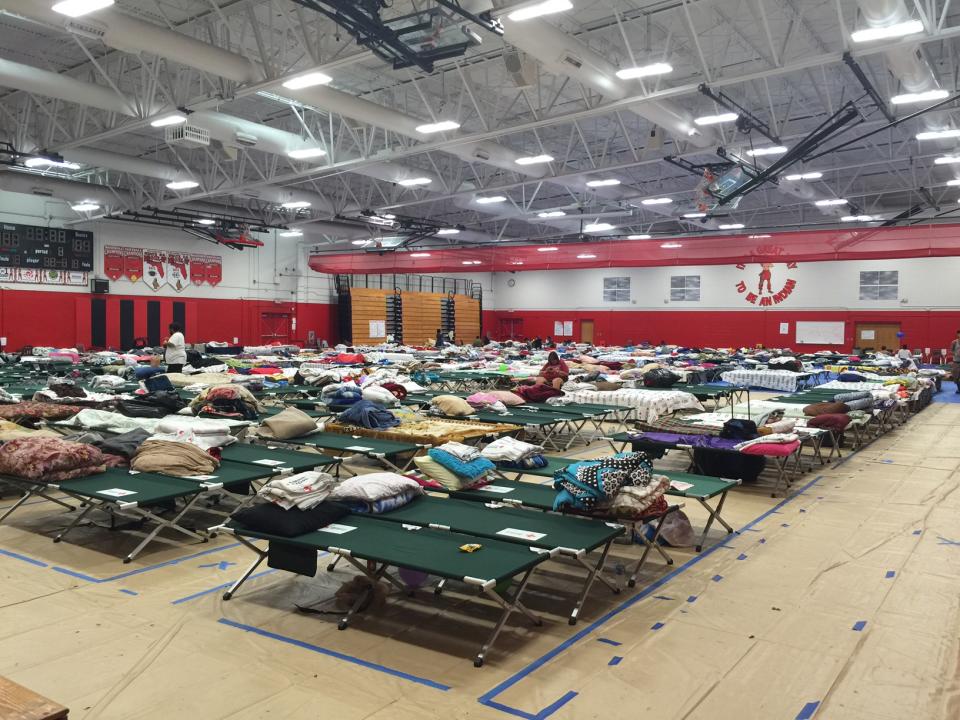

School didn’t start again until this Monday, which was more than two weeks after the storm hit. Part of the reason is because Immokalee High was converted into a shelter. The entrance was filled with Red Cross workers; the gym was filled with cots. FEMA arrived six days after Irma left. Even this week, some in town are still living in tents.

You may not recognize the name Immokalee (rhymes with broccoli). But you probably recognize the most famous Immokalee product: Edgerrin James.

“You don’t understand Immokalee until you leave Immokalee,” he told Yahoo Sports in an interview in Orlando last week. “Once you’re there, that’s your life, that’s what you’re about.”

The NFL Hall of Fame nominee isn’t a big public figure anymore. He spends his days supervising his real estate properties and coaching his two sons, Eden and Edgerrin, Jr. But when he heard about the devastation in his hometown, he rented a U-Haul, filled it with pallets of water, and had it sent to a part of Florida where many gas stations were out and most restaurants were closed. He brought his sons along and put them to work, serving food.

“It was a good feeling to help people,” Edgerrin Jr. says.

The man they call “EJ” doesn’t know a ton about publicity. What he does know is toil.

Everyone here knows toil, no matter how good they are at sports. James’ grandfather was a contractor in the agricultural industry. Vikings rookie Mackenzie Alexander’s dad worked in the fields and still picked tomatoes into his 60s, even as his son closed in on a pro career. Anthony often starts football practices at 5 a.m. because some of his players have after-school jobs. Others have to get home immediately after school because their parents leave town for work and they must watch the younger kids. Football is not a hobby here; it’s a hope. And James symbolizes it.

“He’s the great black hope,” Anthony says. “He has showed us that anything is possible. He notified the colleges that we existed. He may not have been the first but he is prominent.”

Every Immokalee game is a rare opportunity for exposure. Maybe a big tackle or interception gets on film for a recruiter. Maybe someone in the stands sees a spark and tells someone else who tells someone else. Every game is a platform for an out-of-the-way town – especially now.

So in the wake of Irma, the coach balances the need to catch up on football and the need to make sure kids are nourished. The last thing he wants is for kids to be dehydrated or injured. But he also knows there’s urgency: stay with the program, stay with the dream, stay out of trouble.

James’ Hall of Fame nomination matters here, too. He represents his town as few others can. His plaque hangs in the hallway above the entrance to the Immokalee High gym – right above where volunteers brought in food for displaced people.

If James makes the Hall, there’s a chance for more attention on the tiny town that sent him on his way. At least that’s the wish at his high school. Anthony says it often feels like his players are completely overlooked.

“Every [college] thinks we are too small,” he says, “but we have beaten or outplayed schools with big offers.”

One example: senior running back Fred Green, who had three touchdowns and 265 yards in one game already this season. After that game he returned to a home with no power or water. Anthony says his star rusher has no college offers.

“Recruiting is dead!” Anthony laments. “Everyone wants the Alabama formula. What happened to heart and character?”

This is what people here remember about James as much as the highlights. It wasn’t just the statistics – it was the style. “He was tough,” Anthony says. “Like those that lived and worked in Immokalee. And he managed and ran the ball majestically like those that balanced family and work in our community.”

James doesn’t want to go on and on about his career or his candidacy for Canton. He’s happier talking about coaching. But there is one point he wants to make, and it’s relevant to where he came from. He wants to emphasize that he was a good blocker.

“You need three things to be a great running back,” he says. “I did all three of them. The thing you don’t get credit for, the blocking, you’re not going to find anyone who did it too much better than me.”

This is the pride coming out, the feeling that part of his toil has been forgotten. He was an every-down back, just like he was an everyday worker, and he feels that made him complete.

“It’s clear as day,” he says. “Clear as day. Everything is there. One thing is missing – politicking for it. I’m raw and uncut, straight ballplayer.”

James is the “great black hope,” but he knows in Immokalee you build your own hope.

And then you rebuild it.

More NFL on Yahoo Sports