Hurricane Maria cut off a Puerto Rican town. An amateur radio operator found a way out.

As the sun spilled over the storm-stricken mountains of Puerto Rico, all Pedro Labayen could see from his home in Utuado was a river. Hurricane Maria had flooded Avenida Esteves, the town’s main avenue, leaving behind potholes, fallen electric poles and floating cars.

Flash floods destroyed five bridges across the municipality. Furious winds and rains ripped the roofs off over five hundred homes. Four hundred people sheltered in government refuges. Landslides of sandy, volcanic soil destroyed mountain roads.

Behind Labayen’s home, three elderly bedridden sisters perished under an avalanche of mud.

But Labayen, 69, didn’t know yet the proportions of death and destruction that surrounded him. The monstrous 2017 storm had cut off Utuado from the rest of the island and the world.

Labayen was not accustomed to the tsunami of silence. An amateur radio operator for more than 50 years, he had connected daily with people as far as Siberia and India from his home in the Cordillera Central, the sierra that fractures the island in half.

“The world came crashing down here, and we did not know what had happened,” said Labayen.

Power did not come back to the town center until months later. It took a year for some remote parts of Utuado to get electricity back. Equipped with the technology he had loved for decades, Labayen set up a communications system over the airwaves that spanned international borders. It enabled residents to tell loved ones they were alive, coordinate aid for people in need, and notify authorities about new developments.

The harrowing experience inspired Labayen to develop the Plan Comunitario de Comunicaciones de Emergencia de Utuado, the Community Emergency Communications Plan of Utuado. The homegrown network of ham radio operators empowers the mountain municipality’s residents, offering avenues for crisis communication that are resistant to hurricanes, earthquakes and other natural disasters.

“The plan is born here, it is born of need, it is born of suffering, and it is born of wanting to be heard,” Labayen said. “[It] is born from the heart, and it is born from the people.”

‘The radio was all the time there, behind me’

On his 12th Christmas on earth, the Three Kings brought Pedro Labayen a plastic radio and a telegraph key.

“I started hearing people speaking, and I had no idea how it worked,” he said. “I heard people speaking in English, and I couldn’t communicate.”

The blue toy operated on low power, but Labayen managed to make his first-ever contact with a school teacher who lived nearby. During his teen years in the northwestern town of San Sebastián, he would listen in to the citizen frequencies the device picked up.

In 1970, at the age of 19, Labayen studied for his first ham-radio license, allowing him to send and receive transmissions on regulated airwaves. The Federal Communications Commission baptized him as KP4DKE, the call sign he still uses more than 50 years later.

A fellow radioaficionado introduced Labayen to his cousin Maria del Carmen. The pair fell in love and married in 1976. They eventually landed in Utuado, the agricultural stronghold of Puerto Rico where she had grown up.

At the foyer of their historic home in the town center, Labayen set up a hardware and school supply shop. Until the coronavirus pandemic, he sold books and materials to students attending the rural campus of the University of Puerto Rico. Between customers he tuned into the spare radio in the store.

“The radio was all the time there, behind me,” he said.

The Cold War raged on, but Labayen and fellow ham radio fans broke the limitations of borders and governments. The walls of his store became plastered with radio call cards — personalized, postcard-like images ham radio users send each other after making contact over the airwaves.

“Apart from being experimenters, we are ambassadors of peace and good between countries and we exchange our cultures,” he said.

Soviet ham radio operators sent him ornate call cards from Leningrad. Others depicted beautiful shots of faraway places: A bull splashed on a blue background, shipped from famous San Fermín in Spain. Beach shots of Aves Island, an offshore federal department of Venezuela.

Labayen even spoke to monarchs like Hussein of Jordan and Juan Carlos of Spain.

Peter, as he is known in the ham radio world, got on the “honor roll,” the highest distinction an amateur radio operator can receive, for making contact with people in hundreds of countries. As he developed friendships in Russia, Nicaragua and throughout the globe, he also became a cornerstone of the municipality’s crisis responses.

“Radio amateurs are linked to emergencies. When storms came, phones weren’t available. I would participate in all of those events,” Labayen said. “I would go to Civil Defense with my gear. I was the one who supplied the communications at the Utuado level.”

When Category 3 Hurricane Georges devastated Puerto Rico in 1998, Labayen spoke with foreign embassies. When army members in Fort Buchanan, the only federal military installation in the region, couldn’t reach out to superiors in the United States, Labayen linked them.

Twenty years later, Hurricane Maria arrived. The storm struck Utuado and the rest of Puerto Rico with a fury that no living generation had ever witnessed. Like millions of others, Labayen and his wife were left in shock, attempting to grasp the destruction of the landscape before them.

“Usually after hurricanes, I ventured out to find out what was going on. And this time, I didn’t even dare go out,” he said. “I didn’t [think about] going on air to [see] how things are.”

Three days later, a broadcast from Utuado’s local radio station broke the trance.

‘What I need is the radioaficionados’

Maria blew most of the island’s commercial radio stations off the airwaves. Only a handful, including WUPR, the principal radio station in central Puerto Rico, remained in operation. The station’s 11 employees worked through the winds and rains to offer news to the region’s residents.

José Antonio Martínez, the station’s director of 34 years, believes that the historical and institutional knowledge of the station, in operation for almost six decades, allowed it to remain in operation during the storm.

“We already have a lot of experience for more than half a century because we know what we have to do, how we are going to prepare,” said Martinez, who grew up watching his father direct the station through floods and storms.

Before Maria hit, they had removed all equipment from the ground floor of the headquarters and placed it higher up in the building. Martinez brought in a new generator. They cooked churrasco and tostones for dinner. Even as they watched the nearby river overflowing its banks and flooding the first floor, trapping them in the building, the hosts and producers of WUPR stayed on the air.

“We continued working,” he said. “I did not know what was going to happen, but we continued working, and we continued to serve the people.”

Utuado residents with traditional copper-wire landlines, set up by the old Puerto Rico telephone company, could communicate with the station. But Martinez quickly realized that most of his neighbors had no way to get in touch with each other or outside of Utuado.

“I say, we need to have contact with the outside. Everything collapsed, flew away. What I need is the ham radio operators. With the radioaficionados we are going to get the word out and contact the outside world,” he told the Miami Herald. “I immediately called the air and said, I need the radioaficionado Pedro Labayen.”

That same day Labayen waded through the mud, flooding and debris and went to WUPR, usually a 15-minute walk stretched out by the destruction.

The bridge

Before Maria arrived, Labayen tucked away the antennas that usually stuck out from his house like metallic trees to protect them from the storm.

In the aftermath of the hurricane, he set up a simple transmitter on his roof with the help of a neighbor. A solar panel and a car battery zapped his equipment into operation, and Labayen began to scan for signs of life in the vast airwaves.

“I started calling out: ‘I am here, in Utuado, Puerto Rico, and I follow you,” he said.

A station in the neighboring Dominican Republic responded, breaking the stillness of Maria’s silence.

“I told the Dominicans, I need your help. he said. “[And they said], no problem, Peter.”

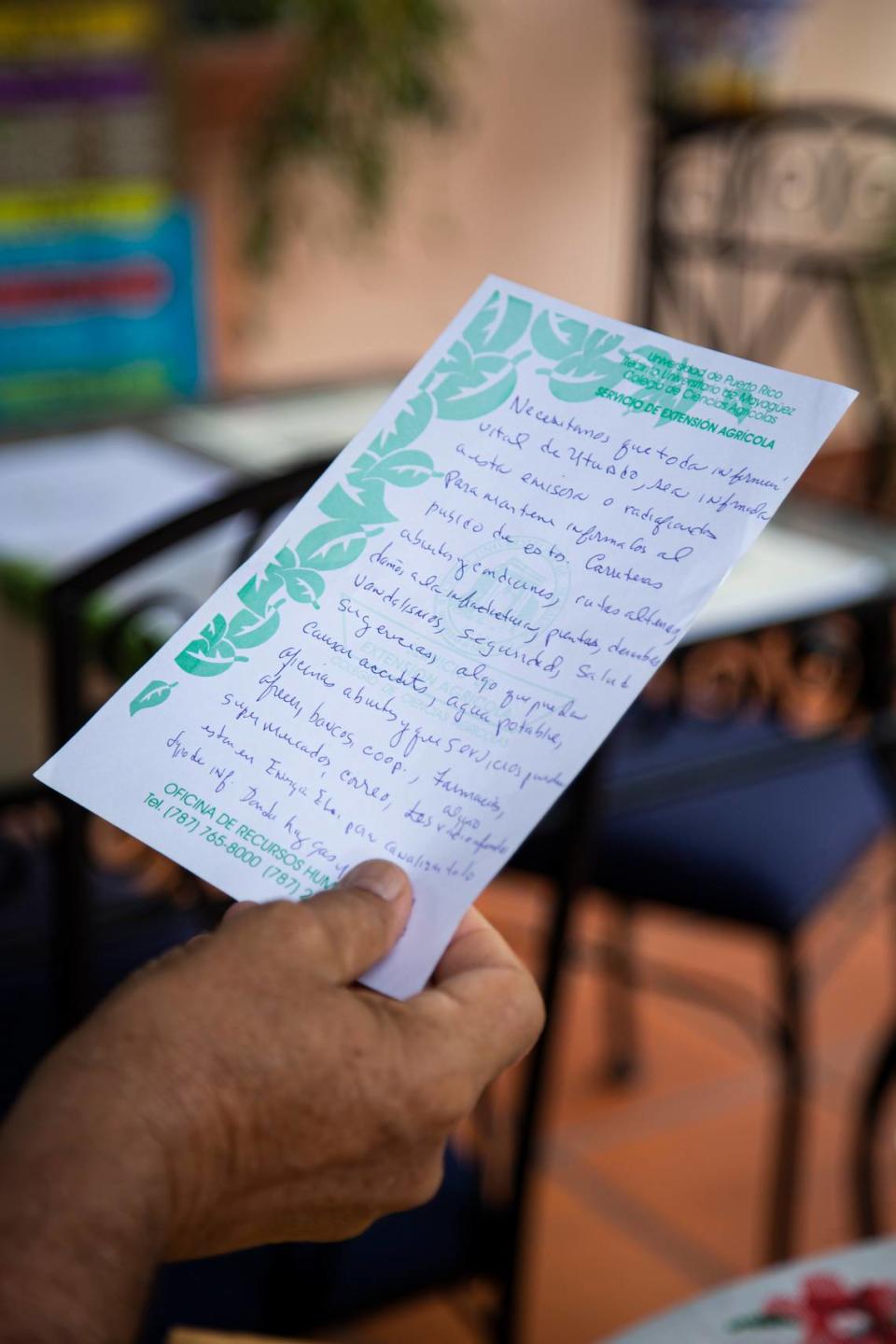

After Martínez’s contact, neighbors and strangers started showing up at the Labayen’s house, bringing hundreds of written messages to his doorstep for him to send out over the radio.

“We are fine. Yesenia lost everything but is fine. Please communicate it to other family members,” reads one message written in blue ink.

“What we need is money for candles, ice, gasoline, batteries. Come take mom,” reads another letter destined for family in the United States.

The radio operator would send signals every morning over the Mona Passage that separates Puerto Rico and Hispaniola. When radio stations in the Dominican Republic responded, “the bridge” — as the system came to be known — settled into place. Peter would share the messages from Utuado, and the Dominican ham radio operators would call their recipients, afterward sharing the replies.

In the afternoons, Labayen made his way on foot to WUPR. Along with a station’s anchor, he read the replies townsfolk had been praying to hear. The replays of Labayen’s transmissions were among the scarce, original programming available on the island.

On air, Labayen shared love letters between couples, stories of romance that kept despairing neighbors afloat. He brought updates of desperately needed supplies that were coming. He coordinated the arrival of aid with authorities. He let people on the ground know how happy their families abroad were that their loved ones were alive.

Through “the bridge,” Labayen facilitated the donation of an electric generator for an 11-year-old bedridden child with respiratory issues and three vans full of supplies through someone from Utuado who lived in Pennsylvania.

“Dear people of Utuado, my most heartfelt words of support and solidarity in the face of the tragedy that we are going through, and my deepest condolences for the families who have lost a loved one,” began one of Labayen’s daily transmissions. “I would like to explain quickly and as simply as possible what a radio operator is.”

From the rolling green landscapes outside the town center of Utuado, 75-year-old Zulma Dueño heard Labayen’s dispatches loud and clear.

‘I was cut off’

Hurricane Maria was the first storm that Dueño weathered in her peach-colored home at the bottom of a tropical, tree-filled hill without the company of her husband, who had died years earlier. One of her daughters lived in Orlando, the other in another town on the island’s northern coast.

The widow prepared for the storm alone, hammering down all doors except for one escape. But the storm came cloaked in the darkness of the night, shaking her home and its wild surroundings with violence.

“I had to get out of the bedrooms. I stayed in the hallway, in a chair, waiting for everything to finish,” she said. “I started to pray because, my God, I felt the windows were going to [blow up.] Never in my life has that happened.”

When morning came, and Dueño opened her front door, she saw a pile of electric cables, roofs, gates and transformers.

“I was cut off,” she said, “I stayed locked up.”

The debris kept Dueño in her home without power for seven days. She couldn’t take out the trash, and ate cans of beans and drank warm sodas. Her family tried to climb through the debris but couldn’t reach her. They wondered if she was dead or alive.

A week later, she was able to get out. That’s when she heard Labayen over the airwaves, one of the first human voices she heard after the storm trapped her.

“He amazed me. I saw that he was communicating with Santo Domingo, she said, and right then and there decided she had to become a radio operator as well.

‘We want to help our people’

As help began to trickle in and officials restored power and cleared roads, people who had witnessed Labayen’s work during Hurricane Maria approached the radio operator. They wanted to learn how to communicate over the airwaves too.

Labayen taught his first radio class of 15 people at the local emergency management office. Then, when one hundred people signed up from towns as far as the coastal cities of Arecibo and Hatillo, the teacher and students migrated to a municipal theater.

”In one of the classes, I asked, what are you all doing here?” he said. “Everyone answered, ‘because we want to help our people.’”

With the support of other radioaficionados, Labayen organized the waves of newly minted radio operators and split Utuado into nine zones.

Under the Community Emergency Communications Plan of Utuado, every neighborhood — from the urbanized core to forested enclaves — has at least one licensed radio operator who can go on the airwaves should telecommunications collapse. Local authorities and emergency services, including police, hospitals, and firefighters, became part of the network. Families and individuals not licensed to operate as ham radio users are taught to use regular hand radios to send and receive messages over public frequencies.

“The plan is meant for the community, for the common citizen, so that they have an alternative means of communication in case of another situation such as María,” Labayen told the Herald.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, Labayen visited neighborhoods across his hometown and over a dozen municipalities, training people in the basics and nuances of ham radio. The Utuado ham radio operators got together weekly at a restaurant to talk shop.

The pandemic has halted in-person events. But from his home in Utuado, Labayen has continued to host weekly meetings over the airwaves for public-band radio users as well as ham amateurs. Over 60 people regularly join the calls. The operators are often timid, but Labayen leads the group through practice exercises. They offer weather reports from their locations and practice how to transmit messages. When the power goes out — a frequent occurrence when it rains — residents use the system to notify emergency management officials that they are without electricity.

Vieques, an island municipality off the eastern coast of Puerto Rico where the only hospital was destroyed by Maria, was the first of Puerto Rico’s towns to replicate Labayen’s plan. And radio operators from other municipalities, including nearby Quebradillas, Barceloneta, Jayuya, often join the meet-ups with the hopes of setting up their own community plan.

When a series of earthquakes struck southwest Puerto Rico in early 2020, which knocked out power across practically the entire island, the Utuado Community Emergency Communications Plan kicked into gear.

“The first thing I did was turn on the radio, and we were all there, like ants,” he recounted. “We were scared, but we were fine. And if something had happened, we were already ready to pass along messages.”

Zulma Dueño becomes KP4ZDR

Dueño was one of Labayen’s first students. For six months she studied around the clock in her home, often sleeping with the instruction book in hand. Practicing hundreds of questions for the examination was daunting, but Dueño was determined to become a radio operator.

After she took the exam, she said, the teacher shook her hand because she had done so well.

About a year after Hurricane Maria confined Zulma Dueño to her home, she was reborn as KP4ZDR, after her initials. She joined the Utuado Radio Amateurs Association, the backbone of the community plan that Labayen leads.

Dueño has found freedom in her radio license. From a table in the kitchen, surrounded by the ham radio certifications and awards she has received, she chats away with other local operators. Should she or a neighbor need assistance in an emergency, she can hook up her radio equipment and seek help.

“As soon as a storm passes, I can communicate with the police, I can communicate with medical emergencies, I can communicate with some other town,” she said.

The town’s radio community, along with Labayen’s plan, has empowered Dueño, giving her the courage to overcome disasters alone and live on her own.

“The Amateur Radio Association for me is a family,” she said, “Because if anything happens to you, they quickly help.”