What hundreds of pages of records reveal about nursing home resident-on-resident violence

John Sullivan's sister was taken aback when she saw his new roommate.

Robert Hill was "a big man," she later recalled in a police interview, "and I could tell that he had a temper."

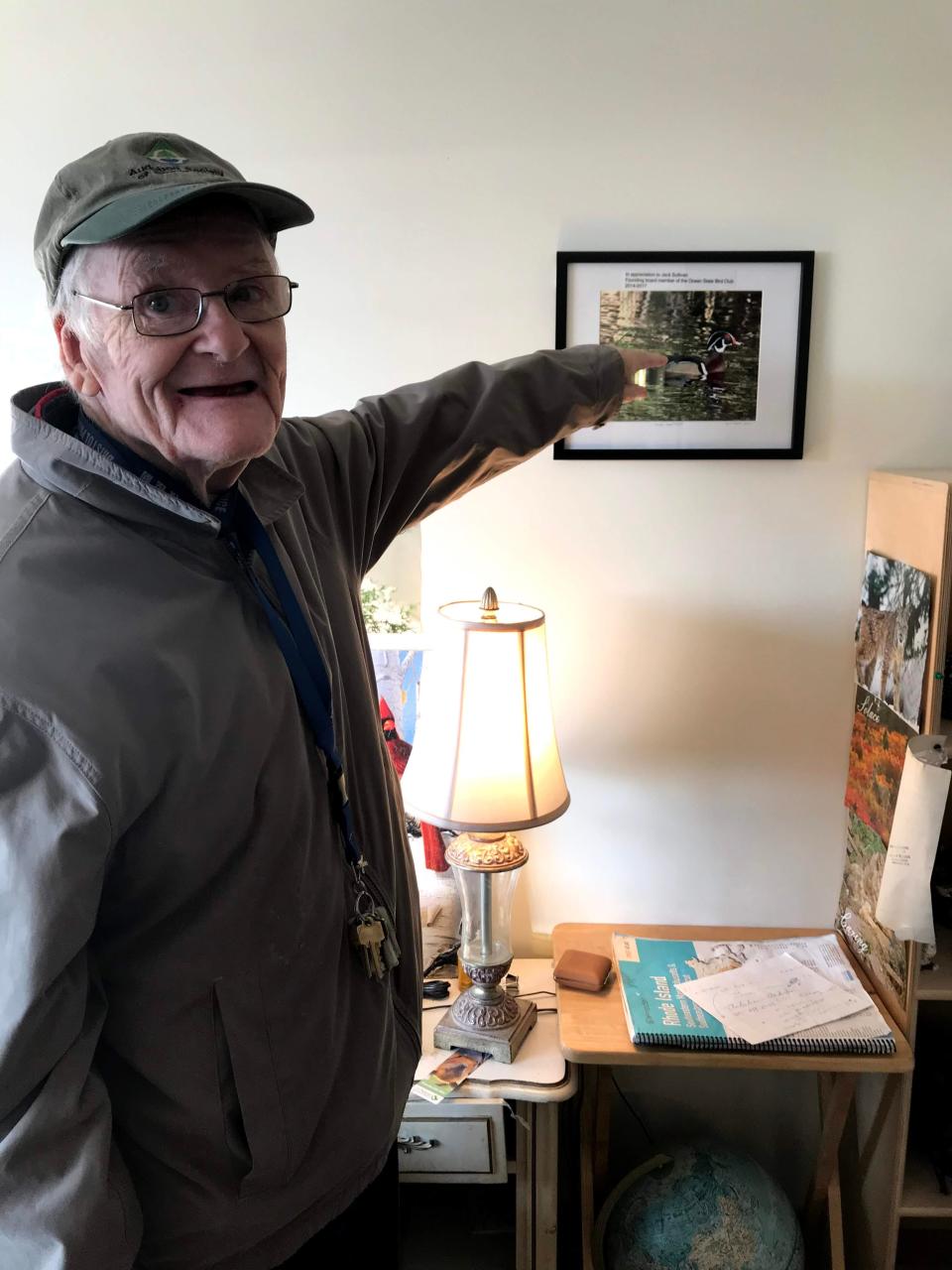

"Jack" Sullivan, by contrast, was frail, bedridden, immobile and could no longer speak. Once an insurance adjuster and outdoorsman who was one of the founding members of the Ocean State Bird Club, the 81-year-old suffered from Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease and was receiving round-the-clock hospice care at Warren’s Crestwood Nursing Home.

His new roommate seemed disoriented, anxious and confused about why he was at the nursing home, Sullivan’s sister noticed. Hill, 76, was loud, so she couldn’t help but hear him arguing with his wife and asking for his keys back.

On the way out, Sullivan's sister stopped by the nurses station to voice her concerns. But there was no one there.

The next day, Sullivan was found dead. He’d been suffocated with the stuffing from a pillow.

"Was it his roommate, Robert Hill?" his sister asked when she got the call. "Did he do it?"

Alarming behavior prompted hospitalization, roommate complaints before tragedy

Just 17 days earlier, Hill had arrived at Crestwood.

Agitated and confused, he repeatedly removed his clothes, refused his medications and tried to escape, staff notes indicated. His first roommate complained about Hill's pacing, and that Hill stared at him as he slept.

A Navy veteran, Hill came to Crestwood instead of returning home after a hospital stay, according to records from the Rhode Island Department of Health. His mental state had declined significantly, and he was suffering from delirium, anxiety, severe cognitive impairment and encephalopathy, which alters brain function.

Three days before allegedly killing his roommate, Hill had an "emotional break" at the nursing home and was found banging a metal hanger on a clock while chanting "Free the people!" He was transported to the hospital, where a doctor suggested antipsychotic medication and a psychiatric evaluation, records show. But that never happened.

At 3:20 a.m. on April 27, 2023, a nurse at Crestwood noted that Hill wasn't sleeping and kept talking about water and ships. "Resident awake for duration of this shift," she wrote. "Agitation, delusions and pacing noted at 12am."

Much later that day, after dinner, Hill urinated on the floor of his room and then became combative with nurses. When a new nurse clocked in for her shift at 10:07 p.m., she went to check on him and was surprised to find the door shut.

Hill tried to stop her from coming in, she later told the police. Forcing her way in, she saw pillow stuffing all over the bed and inside Sullivan's mouth. The older man wasn't breathing.

"He tried to kill me first," Hill told the nursing home's staff. "He's been trying to kill me for 10 years."

What public records reveal about resident-on-resident violence in nursing homes

In the wake of Sullivan's death, The Providence Journal reviewed hundreds of pages of records from local police departments and the Rhode Island Department of Health in order to get a better understanding of how often resident-on-resident violence occurs in nursing homes, what provokes those episodes, and what needs to be done to prevent another tragedy.

Reporters also compiled three years' worth of data in a database that will allow the public to look up incidents at specific nursing homes.

The main takeaways:

The homicide at Crestwood last April was an outlier. In the vast majority of cases, resident-on-resident violence resulted in no injuries, or superficial ones, such as bruises and scratches.

Still, outbursts prompted by the frustrations of communal living can be dangerous, even fatal. At Trinity Health and Rehabilitation Center in Woonsocket, one resident repeatedly turned off their roommate's oxygen tank because they were annoyed by the noise. The roommate went into respiratory distress and died at the hospital last July.

Residents who attacked or sexually abused other residents, including the patient who turned off their roommate's oxygen supply, often had cognitive disorders such as Alzheimer's disease or dementia. Those disorders can lead to aggressive or hypersexual behavior, along with delusions and paranoia, though not all patients exhibit these symptoms.

A significant share of the incidents in the database were reported to the police by a relatively small number of nursing homes. However, that doesn't necessarily mean that there were more incidents at those homes, Kathleen Gerard of Advocates For Better Care in Rhode Island cautioned. Instead, it could indicate that the staff "has been encouraged to report anything that could be construed as abuse of one resident by another resident," she said.

In some cases, residents repeatedly menaced other residents before the facility took action. In October 2021, one resident at the Respiratory & Rehabilitation Center of Rhode Island in Coventry threw another resident on the floor, fracturing their hip. The assailant had been acting aggressively toward other patients at the facility for several months beforehand, the state Department of Health found.

Resident-on-resident sexual abuse is also a cause for concern. Hypersexual behavior can be a symptom of dementia and Alzheimer's, leading patients to behave inappropriately toward other cognitively impaired patients who lack the ability to consent. In June 2022, for instance, the health department found that a resident at Brentwood Nursing Home in Warwick had acted inappropriately toward their roommate on a number of occasions – making suggestive comments, exposing their genitals, and touching the roommate inappropriately. Despite documenting those incidents, the facility did not implement any safeguards to protect the roommate and other residents, regulators determined.

Numerous altercations were provoked by one resident wandering into another resident's room without permission, suggesting that increased supervision could help prevent violent episodes. Disputes over noise or shared bathrooms also frequently triggered disputes among roommates and neighbors.

Nursing home workers are also routinely attacked by combative patients. But while any suspected resident-on-resident violence or staff-on-resident abuse has to be reported to the Department of Health, resident-on-staff incidents do not.

The Journal attempted to contact each of the nursing homes listed in the database by reaching out to their administrators or parent companies. None agreed to an interview.

Athena Health Care, which owns three of the Rhode Island nursing homes in the database – Heatherwood in Newport, Oakland Grove in Woonsocket, and Summit Commons in Providence – issued a statement saying that they "employ a multifaceted approach to ensure residents receive the necessary supportive services, fostering a sense of safety and community engagement."

Brookdale Senior Living, which operates Brookdale South Bay in South Kingstown, provided a statement saying that they have "strict standards in place" and "take any claim of violence or allegation of abuse seriously."

Other facilities declined to comment, or did not respond at all.

What's driving violence and abuse in nursing homes?

After Sullivan was killed, the Rhode Island Department of Health determined that Crestwood had failed to keep him safe. The nursing home hadn't made any changes to Hill's care plan or medication regimen after his breakdown, and they couldn't prove that he'd ever been evaluated by a psychiatrist.

The state issued a finding of "immediate jeopardy," and federal regulators imposed a $216,645 fine.

Hill was charged with first-degree murder but will likely never stand trial. Judicial records show that his arraignment has repeatedly been delayed because he "remains incompetent."

While the severity of the violence was unusual, the Crestwood tragedy otherwise resembled many of the other incidents documented at nursing homes: It involved patients with severe cognitive disabilities who'd been thrust into close proximity.

Understanding what's driving resident-on-resident violence requires understanding disorders such as dementia and Alzheimer's disease, experts say.

Often, when residents with cognitive challenges exhibit problematic behavior, "what's really going on is that we don't understand what they need, because they can't express it to us in language," said Richard Gamache, the CEO of Aldersbridge Communities, a nonprofit facility in East Providence.

A resident who usually gets out of bed at the same time every morning might get aggravated if that routine is disrupted but may be unable to verbalize why they're upset.

Similarly, patients who are experiencing physical pain may act out when they're not able to communicate that.

"Dementia can also inflate simple moments of unpleasantness," said John Gage, CEO of the Rhode Island Health Care Association. "Someone may look at someone the wrong way, or someone is in someone else’s space. And then tomorrow, that same person could be your best friend."

Another factor: Nursing homes no longer just take care of "little old ladies or little old men," as Jesse Martin, executive vice president of SEIU 1199 New England, put it. Instead, they're increasingly admitting younger patients with psychiatric issues or substance use disorders.

For instance, Martin said, if a 25-year-old experiencing homelessness gets hit by a car and has two broken legs, they probably won't have anywhere to go when they're discharged from the hospital. But Medicaid will pay for them to stay at a nursing home while they recover.

Those patients may not live in the same unit as older, more traditional nursing home residents, "but they use the same dining room, they go to the same activities," Martin said. A 25-year-old who's struggling with addiction or behavioral issues – and accustomed to living independently – may grow increasingly frustrated with meals, activities and schedules that are designed for elderly retirees.

"Do you know the amount of pent-up rage that person has at being forced to eat a breakfast at 7 a.m.?" Martin asked rhetorically. "You’re placing people, because of their poverty and their needs, in inappropriate care settings that then become a powder keg of violence."

In the coming weeks, The Journal will be examining how authorities deal with resident-on-resident violence and abuse in nursing homes, what needs to happen to prevent these incidents from occurring, and the way the court system handles mentally incompetent defendants.

You can browse all the incidents in the database or look up specific nursing homes here:

Loading...

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Violence and abuse in RI nursing homes: What our investigation found