What House Democrats can, and can't, do to push action on climate

The new Democratic majority in the House is launching an aggressive campaign to prioritize the climate crisis and hold the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) more accountable than the previous leadership has.

This renewed attention was evident from the first day of the 116th Congress, when House Speaker Nancy Pelosi received a standing ovation after calling anthropogenic (human-caused) global warming “the existential threat of our time.”

“The American people understand the urgency. The people are ahead of the Congress. The Congress must join them,” Pelosi said.

But President Trump has called climate change a hoax, and Republicans still control the Senate, so what can the House actually do to bring about change?

Gene Karpinski, the president of the League of Conservation Voters (LCV), sees three ways the new House can actually make progress in this situation: using the oversight process to hold the EPA and Interior Department officials accountable for “doing the bidding” of polluters; making sure relevant committees hold hearings on climate change to elevate the conversation; and advancing legislation that moves the conversation in that direction — even if the bills don’t make it into law.

“That would include making sure the infrastructure bill has emissions reduction targets” that spell out the impacts of any projects on carbon pollution. Karpinski told Yahoo News. “That will include a lot of other aggressive measures to get the House members on record — which they clearly want to be — in favor of visionary proposals to move us forward.”

Karpinski said those proposals aren’t necessarily going to become law in the next two years, but they will set the agenda for legislation when pro-environment policies return to the White House and Senate.

On its first day, the House voted to create a Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, which will be led by Rep. Kathy Castor, D-Fla. That committee essentially restores the House Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming that had been established in March 2007 — during Pelosi’s first year as speaker — and lasted until 2011, when the GOP took control of the 112th Congress.

As the select committee draws renewed attention to the issue, three standing committees will have the ability to organize hearings on climate change: Natural Resources, Energy and Commerce, and Science, Space and Technology.

John Bowman, the director of federal affairs for the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), thinks the new Congress should focus on repairing America’s rundown infrastructure in a way that simultaneously accounts for its current shortcomings and future storm projections.

“You could rebuild our aging transportation infrastructure, highways, bridges and roads in a resilient way so they are able to weather the storms that have become stronger and more constant,” he said.

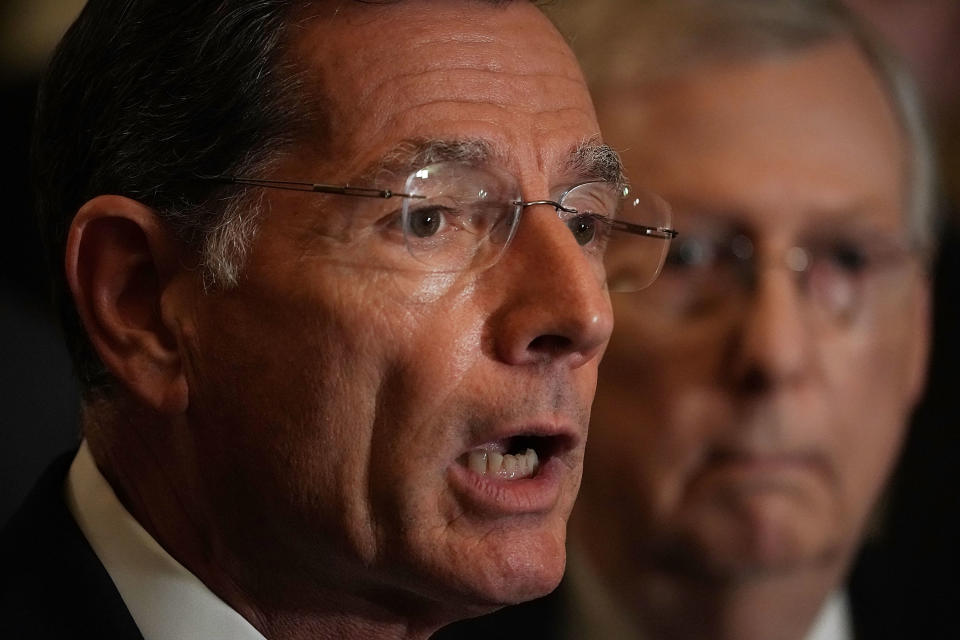

Bowman hopes the House will serve as a meaningful check on the GOP-controlled Senate and the Trump White House, but he isn’t overly optimistic that Congress will pass comprehensive legislation that addresses the danger of climate change. It’s doubtful that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell would take up such legislation, even if it passes the House.

“Divided government is very hard. Mr. McConnell is a committee of one in deciding what the Senate takes up. If he decides not to take a House-passed bill to the floor in the Senate, that’s something he can do,” Bowman said.

Sara Chieffo, the vice president of government affairs for LCV, said she is hopeful that House committees will lay out to the public just how influential corporate interests and fossil fuel companies have been in shaping the Trump administration’s rollbacks.

“Oversight looks like bringing up the administration officials repeatedly to see what they’ve been doing, requests for documents that have been held behind closed doors. It looks like we could see some legislation, but it really is much more the ability to haul folks up and present documents and present that case to the public,” Chieffo told Yahoo News.

She added that former EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt and former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke aren’t immune to being called up.

On Jan. 8, Rep. Frank Pallone, D-N.J., chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, reintroduced the COAST Anti-Drilling Act to prohibit the Interior Department from authorizing anyone to drill for oil or natural gas off the East Coast, including the Atlantic Ocean, Straits of Florida, and the eastern Gulf of Mexico.

“We must continue to fight against the Trump Administration’s reckless assault on our coastal waters. New Jersey has so much at stake with miles of beautiful beaches, $700 billion in coastal properties, and a tourism industry that generates $38 billion,” Pallone tweeted.

The bipartisan bill was supported by every member of New Jersey’s delegation, including freshman representatives Mikie Sherrill, Tom Malinowski, Andy Kim, and Jeff Van Drew.

But the Trump administration is still moving in the other direction.

On Jan. 9, Trump nominated former coal lobbyist Andrew Wheeler to become the permanent EPA administrator. He has been the acting administrator since Pruitt resigned amid ethics scandals in July. He will need to be confirmed by the Senate again to be the agency’s official leader.

Although Republicans control the Senate, the Democrats on the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee used Wheeler’s confirmation hearing on Wednesday to highlight the discrepancy between the recommendations of scientists concerning fossil fuel reduction and his policies. For the rest of the Senate, the vote on Wheeler’s confirmation could signify a commitment — or lack of one — to climate policy.

Wheeler’s tenure so far has demonstrated that he’s continuing Pruitt’s deregulatory policy — albeit with more tact. He proposed a rule to soften fuel-efficiency and tailpipe pollution standards for automobiles and revoke California’s right to set its own stricter standards. He also proposed replacing the Clean Power Plan so states could decide whether to restrict pollution from power plants at all. (The agency’s own analysis concluded that this could result in up to 1,400 premature deaths each year by 2030.) And in December he proposed drastically cutting Clean Water Act protections, which critics say would allow industry to dump toxic waste and other pollutants in America’s waterways.

So far, climate policy has been made according to the norms of politics as usual: checks and balances, impassioned speeches, ill-fated though principled bills. However, as temperatures continue to rise, extreme weather events become more disastrous and pleas from scientists become more frequent, there are signs the public is losing patience with politics as usual.

The Environmental Entrepreneurs (E2) advocacy group organized a letter to every member of the new Congress imploring them to “take immediate and ambitious action” to address the economic threats of climate change. It was signed by more than 500 business leaders and other professionals and was released on Jan. 8.

“Congress has not only the power, but the obligation, to act to prevent the worst effects of climate change as soon as possible,” the letter reads. “Congress has debated this topic for decades, including examining the human influence of climate change in high profile hearings held in 1988. The 116th Congress can wait no longer to act.”

Many lawmakers have taken up this challenge — none more conspicuously than Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y. She adopted the concept of a “Green New Deal” as central to her campaign and pushed it into the mainstream by joining a protest last November in Pelosi’s office where demonstrators held signs reading “green jobs for all.”

The phrase Green New Deal was coined by New York Times columnist Thomas L. Friedman in 2007. He was inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, a response to the Great Depression of the 1930s, which combined banking reforms and public works projects. Friedman was advocating tax incentives, research funding and government loan guarantees rather than large-scale federally funded projects.

But the idea took on a life of its own among democratic socialist circles. Green Party candidates such as Jill Stein started to champion the idea of transitioning the nation to 100 percent clean, renewable energy for electricity by the 2030s. According to its supporters, this would provide “jobs for all” and cut the nation’s carbon footprint.

Ocasio-Cortez’s bold actions have made her a superstar to the left and a villain to the right. Conservatives pounced on her “60 Minutes” appearance, in which she struggled to explain to Anderson Cooper how it would be possible for America to transition to zero carbon emissions within 12 years.

Rather than spell out precisely how America could do that, she said, “It’s going to require a lot of rapid change that we don’t even conceive as possible right now.”

And therein lies a major divide among the left between experienced, moderate Democrats willing to work within the normal channels and fresh, radical Democrats who think it’s better to shoot for the moon than try to compromise with climate deniers.

The Green New Deal has since been embraced by Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass.; Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J.; and Democratic presidential candidate Julián Castro. Ocasio-Cortez is planning to introduce Green New Deal legislation.

Scientists say that climate change is already here and that enormous systemic changes are needed to avoid the worst impacts in the years to come. But America’s separation of powers makes change slow and laborious — protecting the nation from overhasty action but also creating the opportunity for gridlock.

With these conversations brewing on Capitol Hill, is it probable that House Democrats can effect change through oversight, public hearings and proposals? Maybe, maybe not. But these are the strategies available to them until Republican politicians recognize the reality of climate change as much as their constituents do or until Democrats win the Senate and White House.

According to Chieffo, “This is really a freshman class for the history books but also, from where we sit, an unprecedented number of candidates who ran because they cared about the climate specifically and came with a commitment and background in these issues.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

2020 prospect Sen. Klobuchar: It’s ‘difficult to imagine’ voting for Trump AG pick

Despite denials, documents reveal U.S. training UAE forces for combat in Yemen

Ted Kennedy, Jimmy Carter and a lesson from history for President Trump

Mayor Pete to President Pete? It’s crazy, but he thinks his ideas aren’t.