Hope Hicks tells hush-money jury of Trump’s control over 2016 campaign

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

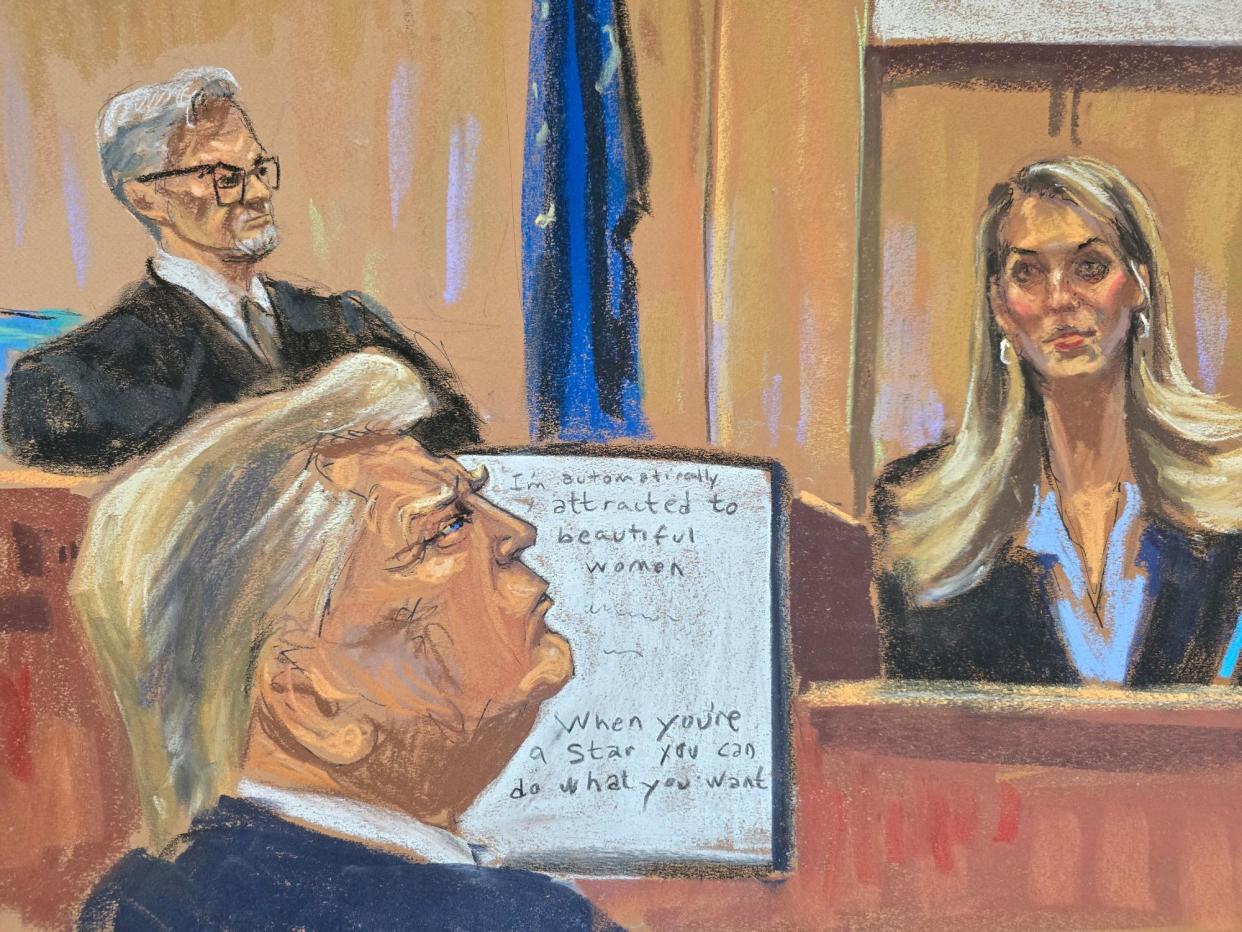

Hope Hicks, Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign press secretary, broke into tears on Friday while testifying in the ex-president’s New York criminal hush-money trial, hours after she described his complete control over the campaign.

Hicks, who cut a skittish figure in Judge Juan Merchan’s courtroom, is a key prosecution witness. She described Trump campaign staffers’ panic when a recording emerged in which Trump bragged about groping women. “This was a crisis” for his presidential bid, she said, describing the sentiment among the campaign staff.

Hicks also placed Trump squarely at the center of his campaign media strategy, telling jurors “we were all just following his lead”. The testimony marks a turning point for prosecutors, as she is the first Trump staffer with intimate knowledge of Trump’s campaign to testify about his alleged misconduct.

Prosecutors allege that he tried to use payoffs to bury stories that could harm his candidacy. While her name has come up at various points during the trial, Hicks’s placement of Trump in the middle of this alleged media strategy is a stunning development.

“Who overall was responsible for branding strategy?” prosecutor Matthew Colangelo asked.

“I would say that Mr Trump was responsible,” Hicks said. “He deserves the credit for the different messages that the campaign focused on in terms of the agenda that he put forth.”

Hicks – who reportedly had a close relationship with Trump until her anger about the January 6 insurrection surfaced – was clearly uncomfortable. When Hicks walked to the witness stand on Friday in the ex-president’s New York criminal hush-money trial, he traced her with his eyes as she passed him. Hicks, a willowy figure who crossed into the well with small steps, had a quavering voice as she introduced herself to jurors.

“My name is Hope Charlotte Hicks, and my last name is spelled H-I-C-K-S,” she said. Unsure the mic was picking up her voice, she said: “I’m really nervous.”

Hicks, who was repeatedly interviewed by Robert Mueller due to her longtime proximity to Trump, also served in the White House as his communications director.

When Hicks was questioned about the Access Hollywood tape that leaked in early October 2016 – in which Trump notoriously boasted that when a man is famous, he can “grab [women] by the pussy” – jurors were shown a transcript of the tape.

Asked what her first reaction was to receiving an email from a Washington Post reporter about the tape, Hicks said she was “very concerned” about the contents of the email, and the lack of time to respond.

She says she forwarded the email with the subject line: “URGENT WashPost query” to others in the campaign. “It was a damaging development,” Hicks said. “[The] consensus among us that this was damaging – this was a crisis.”

Former tabloid honcho David Pecker – whom prosecutors said colluded with Trump and Michael Cohen to bury stories that could hurt his campaign – said Hicks was present at the trio’s summer 2015 Trump Tower meeting.

Pecker also testified that Hicks was present on a call in which Trump railed angrily about one of his alleged paramours doing TV interviews. Manhattan prosecutors contend that Cohen bought Daniels’s silence about a claimed sexual liaison with Trump for $130,000.

They say that he coordinated the National Enquirer parent company AMI’s payoff to Karen McDougal, a Playboy model who also alleged a sexual relationship with Trump. They allege that Cohen did so to prevent damaging information from thwarting Trump’s presidential bid.

Trump faces counts for allegedly falsifying business records, by describing repayments to Cohen as legal expenses on his company’s documents. Prosecutors contended that Trump, Cohen and Pecker hatched their catch-and-kill scheme during that summer 2015 meeting at Trump Tower.

Hicks was also asked on Friday about a media inquiry from the Wall Street Journal, which was running a story in early November 2016 about AMI’s purchase of Daniels and McDougals’ stories – and failure to run them. Hicks said that she thought she had spoken with Trump after getting this inquiry.

“He wanted to know the context and he wanted to make sure there was a denial of any kind of relationship,” Hicks said, expressing confusion as to why he wanted to do that. “I felt the point of the story was that National Enquirer paid a woman for her story and never published it.”

Jurors were also shown text messages between Hicks and Cohen in which she repeatedly told him to “pray!” that the 4 November 2016 Wall Street Journal article on AMI’s purchase of Daniels’s and McDougal’s stories would not gain traction.

At this point of her testimony, Hicks seemed to appreciate the absurdity of this situation. When she read aloud Cohen’s text about the article, calling it “poorly written and I don’t see it getting much play”, Hicks chuckled. “A little irony there,” she remarked, and again laughed softly. “I said I agree with that.”

Even though the Journal story did not tank Trump’s campaign, or get all that much attention at the time, Hicks said that he was still worried – including about Melania Trump catching word of the coverage. “He wanted me to make sure that the newspapers were [not] delivered to their residence that morning,” Hicks told jurors.

Whatever humor might have emerged from recalling her exchange with Cohen dissipated shortly thereafter. Right when Trump attorney Emil Bove started his cross-examination of Hicks, as he gently asked about the commencement of her career with Trump, she choked up.

Merchan asked Hicks whether she needed to take a break.

“Uhm, yes, please,” she said.

As Hicks walked out of Merchan’s courtroom, a piece of balled up tissue could be seen in her hand.