Homelessness, up in 2017, doesn't take a break for Christmas

Every year around Christmas, a section of Union Square Park in New York City is blocked off for a holiday market of winding aisles lined with sales booths. Right across 14th Street, outside trendy stores, people huddled under blankets are asking for change from passersby on their way to buy knickknacks and stocking stuffers.

Income inequality is stark throughout the United States. New York City is among the places where it’s particularly acute, especially around Christmastime — a season of paradoxical compassion and materialism.

New York is experiencing its greatest homelessness crisis since the Great Depression — we just can’t see it. This fact may elicit cognitive dissonance for New Yorkers who lived through the urban decay of the ’70s and ’80s. That’s largely because New York has a “right to shelter law” on the books. A survey on one night in January found 76,501 homeless, an increase of 4.1 percent from 2016, and a little less than the 1 percent of the city’s population. But only 3,936 were sleeping on the streets — 72,565 were in shelters.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) annual assessment report to Congress for 2017 found that total homelessness in the U.S. increased for the first time since 2010. The one-night survey, involving tens of thousands of volunteers in some 3,000 cities and counties, counted 553,742 homeless people, an increase of 0.7 percent since the 2016 count. Overall, 360,867 people were located in transitional housing and emergency shelters while 192,875 were in unsheltered locations.

Homelessness actually declined in 30 states and the District of Columbia between 2016 and 2017, but that was offset by increases in major cities. A combination of rapidly rising rents and stagnant wages in high-cost cities like Los Angeles and New York has driven low-income people out of their homes. In Los Angeles alone, overall homelessness increased nearly 26 percent to 55,188 since last year, mostly on the streets.

Advocates for the homeless say poor Americans are facing one of the worst crises in affordable housing in U.S. history. Year after year, rents have been rising faster than the rate of inflation and average hourly earnings in 89 of the country’s 100 largest cities, according to the December 2017 Apartment List National Report.

“New York is seeing a substantial increase in the number of sheltered families with kids. Meanwhile, you go to the West Coast and the story is largely unsheltered, individual men. So you have a street problem on the West Coast and a shelter problem in New York,” HUD spokesman Brian Sullivan told Yahoo News.

The results of the January count were analyzed during the year, and the HUD report was released on Dec. 6. There will be another count in January 2018. Sullivan said this data is extremely helpful for local planners but is not without its limitations.

“It is comprehensive in that it includes both people in shelters and unsheltered, but it’s only over one night, so it’s like taking a picture of homelessness. As time has gone on, that picture has become clearer and clearer,” Sullivan said. “But it’s still just like a picture and like any picture, if you’re not in it, you don’t appear to be there.”

The Coalition for the Homeless, a nonprofit advocacy group, said demand for shelter in New York City increased 79 percent in the last decade. As people moved to larger cities, rents went up but earnings did not. This gap is particularly acute for people on the lowest end of the income spectrum and is considered the main cause of homelessness at this point.

Giselle Routhier, the policy director for the NYC-based Coalition for the Homeless, told Yahoo News that the city hit a new record in October 2017 for the most people living in shelters operated by the Department of Homeless Services each night: 62,963. The HUD numbers from January are higher because they also count people staying in shelters for runaway youth (operated by the Department of Youth and Community Development) and for victims of domestic violence.

She said that former New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg exacerbated the problem by ending a program that paid rent subsidies to homeless families moving out of shelters; Bloomberg said the program had the unintended consequence of drawing people into the shelter system in order to qualify for the benefits, an example of the Catch-22 phenomenon that makes this such an intractable problem.

According to Routhier, New York is still dealing with the aftermath of Bloomberg’s decision. She said that despite some positive steps — investing in homelessness prevention, legal services, etc. — Mayor Bill de Blasio has not done anything to meaningfully reduce the shelter census. The escalating homelessness rates are arguably among the biggest failures of de Blasio’s administration.

“We’re facing homelessness now at a level that it’s never existed before, and the solution needs to match that scale. We’ve been pushing the city to double the affordable housing resources that it has and thinking about its new Housing New York plan,” she said.

The de Blasio administration plans to phase out the 17-year-old cluster site program: The city pays big bucks to rent out often-shabby private apartments to house homeless people. Critics say this program created harmful incentives for landlords.

On Dec. 12, de Blasio announced that the city would instead help nonprofit developers purchase controversial “cluster site” buildings and convert them into permanent affordable housing. As a last resort, the city will take the properties by eminent domain.

According to the mayor’s office, the city has identified up to 30 buildings that qualify for purchase and conversion, where 50 percent or more of the apartments are cluster apartments. About 800 families and 300 others seek shelter in these buildings, so their conversion would hypothetically create around 1,100 affordable homes. The new owners would enter into regulatory agreements with the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development to keep the properties affordable.

New York’s reliance on cluster units peaked at about 3,600 in January 2016, but that figure dropped to 2,272 by December 2017.

“We’re not facing the same problems that they are in L.A. and Seattle, where there are massive tent camps under freeways and families are living on the street or in vans,” Routhier said. “We should be proud of that, but it’s all the more reason for us to get the word out there and let people know that it’s a dire situation.”

Despite New York’s “right to shelter” law, some people experiencing homelessness have their own reasons for avoiding the shelters.

Total homelessness in Los Angeles went from 43,854 in 2016 to 55,188 in 2017, according to the HUD report. Los Angelenos would be hard-pressed not to see the 41,216 people living on the streets, as only 13,972 people were in shelters.

Nan Roman, the president and CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness, said Los Angeles County has never had a lot of shelter beds relative to its large population of over 10 million.

“In Los Angeles, the feeling that there’s a lot of unsheltered people is growing as people are getting pushed out of the Skid Row area by development there and spreading across the city,” Roman told Yahoo News.

She pointed out that some other warm cities, such as Miami, don’t have the same high unsheltered homelessness rates. The other West Coast cities that share L.A.’s high homelessness rates also have high housing costs.

The National Alliance to End Homelessness, which has been around since the early ’80s, collects data from local communities to determine the most effective strategies for combating homelessness. The organization works with multiple levels of government to put these policies into action. They have recently been working on supporting rapid rehousing programs that connect individuals and families experiencing homelessness with permanent housing.

Roman said it’s important to keep in mind that homelessness has been going down recently, but the fact that it’s picked up a little this year is a disappointment — even if the increase is less than 1 percent and driven mostly by increases in Los Angeles.

“That’s a disappointment, and it’s something for us to worry about. I think we were making progress,” she said. “It’s distressing that for the first time in seven years it didn’t go down.”

HUD Secretary Ben Carson said eliminating homelessness is within reach but that it will take the private and public sectors working together. “Increasing homelessness, long waiting lists for people get into affordable housing is not just the federal government’s problem. It’s all of our problem. It’s a societal problem,” Carson told reporters on a conference call announcing the HUD data. “And the solutions occur when we are willing to work together, recognizing that if we create the right kinds of environments for our people, it leads to much more development.”

Carson pointed out that despite this year’s recorded increase in people experiencing homelessness, there has been an overall decrease in the past decade and a half. The overall figure of 800,000 people homeless 15 years ago was much higher than this year’s roughly 554,000 people, he said.

On the same press call, Matthew Doherty, the executive director of the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH), pointed out there’s a great deal of local and regional variation within the data. He said there’s a lot of evidence that current strategies and best practices are helping, citing Housing First, the approach of connecting individuals and families facing homelessness to permanent housing without any preconditions, such as sobriety or service participation.

“Housing First works. When we get people into housing as quickly as possible with the right amount of services to make sure they can succeed, we can end homelessness for everyone — regardless of their challenges,” Doherty said. “Housing First practices and programs are driving progress when communities can take those solutions to the scale needed to match the scale of need.”

Government agencies are trying to address homelessness on a massive scale. But smaller groups and organizations are trying to address the problem on a local or community scale.

The Bowery Mission is a Christian shelter in downtown Manhattan that serves the local homeless population. The organization serves breakfast, lunch and dinner every day of the year at its headquarters on the Bowery, preceded by a chapel service. It also offers recovery programs that help homeless people break self-destructive habits, meet their basic needs, find employment and reenter society.

Edward Chavitz, 33, began 2017 sleeping on subway trains to stay out of the cold because he had been evicted from his apartment in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. Over the course of this year, he got involved in the Bowery Mission’s Life Transformation Program. Now he’s living in the program’s East Harlem dormitory with 80 other men, learning about how he can renter the workforce.

“I’m not getting into trouble. I’m not fighting with nobody on the streets for a park bench to sleep on, or making sure nobody tries to rob me while I’m sleeping on the bench. I’m transforming my life,” he said.

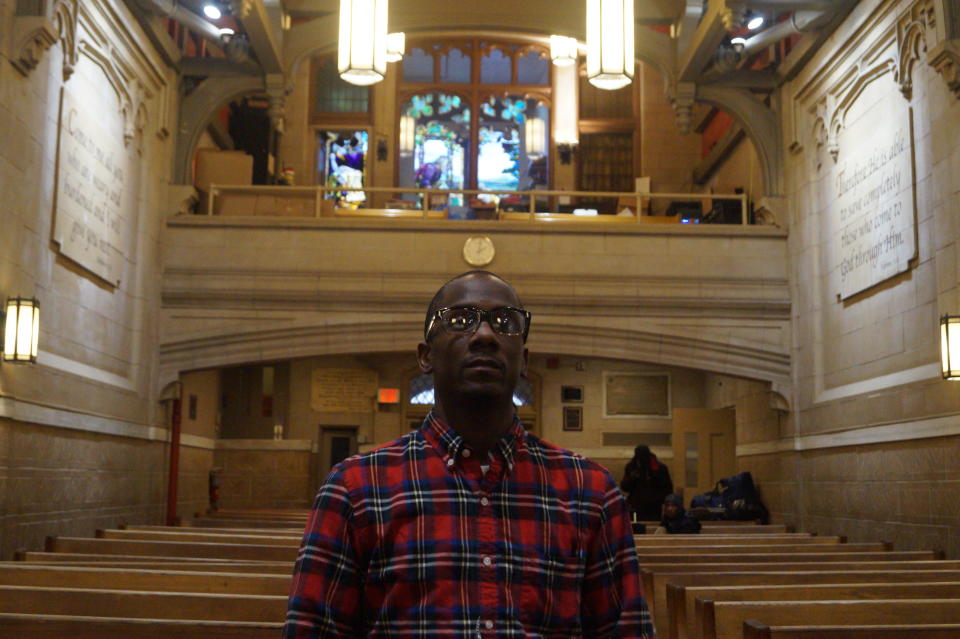

William Barfield, 45, went homeless in New York this year. He doesn’t think the government or society have sufficiently responded to the scope of the crisis.

“People are always looking down on the homeless people like they are a piece of mess. But it’s not like that. You have to be kinder. America needs to reach out more to the homeless people and stop judging them all the time because it could be you the next day,” Barfield told Yahoo News.

Barfield, who was raised in Newark, N.J., also got involved in the Bowery Mission recently. Barfield thinks the group’s spiritual foundation has helped him get through hard times, and he was particularly moved by the outpouring of compassion he saw for the needy and working poor this month.

“It felt so good to see a place giving back to the community. And more places need to do that around Christmas,” he said. “A lot of people don’t have family. They’re lonely. Different places need to give back to the homeless, and let them know they have some place to come to start the New Year fresh.”

James Winans, the chief development officer at the Bowery Mission, is equally touched by the kindheartedness and altruism he sees each year around the holidays. He only wishes that more people carried this Christmas spirit with them into the new year.

“Over the holidays the Bowery Mission sees many more people coming in with donations, wanting to volunteer, wanting to give back,” he told Yahoo News. “The challenge of course is that we’re doing this 365 days a year, so after Christmas is over, we’re hoping that people will remember us, because we need people every single day of the year here.”

Read more from Yahoo News: