Hillary wades into impeachment in Watergate interview

Hillary Clinton has a message for lawmakers contemplating impeachment: Steer clear of politics, don’t hold press conferences and avoid leaks.

The former secretary of state’s advice came in a little-noticed interview conducted last July as part of an oral history project tied to the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, and quietly published earlier this summer. The interview amounts to some of her most extensive public comments on impeachment, and a fascinating window into her current thinking on the subject as House Democrats contemplate ousting yet another Republican president.

Related Video: Hillary Clinton Slammed Trump’s Racist Attacks on Dem. Congresswomen

While President Donald Trump’s name didn’t come up during the hour-long sit-down, the man who bested Clinton in the 2016 general election looms over her answers as she opined from a perspective no one else in American history can claim: First as a young law-school graduate working for the Democrat-led committee that voted to remove Nixon and then more than two decades later as first lady when Republicans tried without success in the late 1990s to oust her husband, President Bill Clinton.

“I think that it's such a serious undertaking. Do not pursue it for trivial partisan political purposes. If it does fall to you while you're in the House to examine abuses of power by the president, be as circumspect and careful as John Doar was,” Clinton said of the Judiciary Committee’s lead impeachment staffer, a Republican who served as a civil rights chief during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

“Restrain yourself from grandstanding and holding news conferences and playing to your base,” Clinton added. “This goes way beyond whose side...you’re on or who's on your side. And try to be faithful purveyors of the history and the solemnity of the process.”

Hillary Rodham, as she was known when she started as a 26-year old staffer on the House Judiciary Committee — she had not yet passed the bar exam in Washington, D.C. — described in the interview working 16 or 18-hour days without weekends conducting research on the basic tenets of impeachment.

It was January 1974, and one of her first assignments involved learning about the basic procedures for removing a president in both the House and Senate, as well as the history involved in the unsuccessful 1868 attempt to remove President Andrew Johnson over his handling of reconstruction after the Civil War, as well as earlier English common law precedents that inspired the removal section in the Constitution.

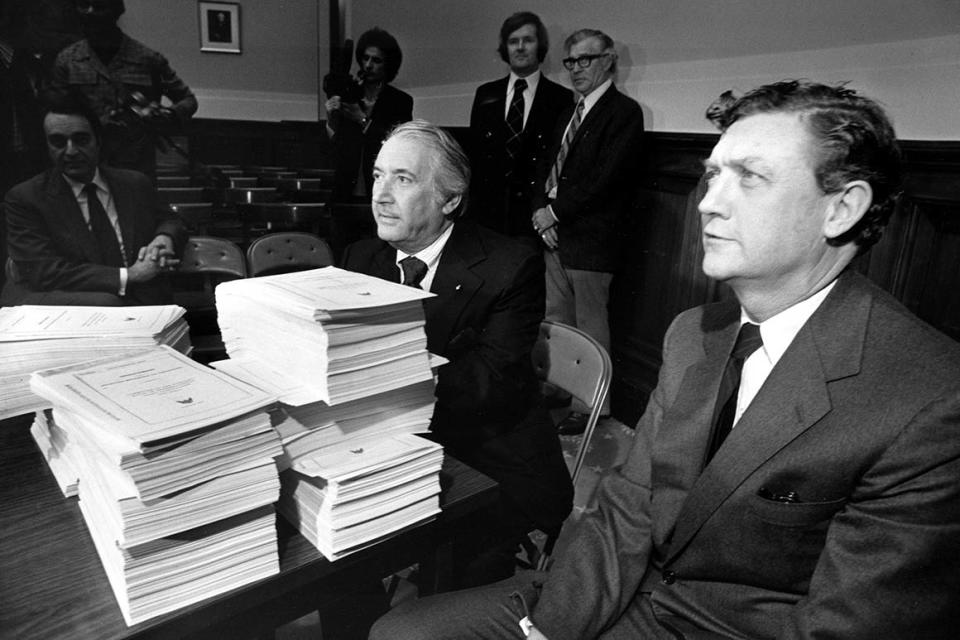

Rodham and her colleague on the committee staff, future Massachusetts governor Bill Weld, were assigned the task on a Friday and asked to have the memo on Doar’s desk by the following Tuesday. With so little to go on, she said, the process assumed an ad hoc quality.

“We were trying to impose an understanding of the law and the history combined with a process that would be viewed as fair, providing due process to the president if articles of impeachment were decided,” she said. “So we were trying to rely on precedents as much as we could, but we were kind of making it up based on our best understanding of the law as we researched it.”

Clinton also played a role in helping the committee identify the facts for an impeachment investigation of Nixon surrounding Watergate, the 1972 break-in of the Democratic National Committee headquarters and the Nixon administration’s attempts to cover up its involvement in that effort.

One of the jobs she talked about involved transcribing a White House audio tape of Nixon listening to other tapes — committee aides called it the “tape of tapes” — that he’d been secretly recording of his conversations and phone calls with aides and advisers.

“So, we would sit there with the headphones on, just exhaustingly listening, trying to make out words,” she said. “Some of the transcription already occurred, but some of it was garbled, it was not at all clear. But the tape of tapes was a big revelation to me. I had no idea that he would be taping himself listening to tapes and then coming up with rationalizations. So, he would call somebody into the room, and he would say, ‘I want to play this for you. Now when I said that, here's what I meant.’ So, it was really a shocking experience.”

That specific experience, Clinton said, helped convince her that Nixon had obstructed justice.

“I think for me it was listening to the tapes, and particularly the so called tape of tapes because it was almost a textbook example of someone trying to get stories straight and getting other people to get their stories straight,” she said.

Doar tried to enforce strict rules that included requiring all aides to maintain their poker faces in hearings and meetings with lawmakers, Clinton said.

“He said, ‘Don't talk to anybody. Don't make facial expressions. Don't portray any opinion. We were there just to make a presentation to the members of the committee.’ So, it was a matter of honor that we would maintain the secrecy that was so critical for this, for this whole investigation,” she said.

Doar’s mandate, Clinton said, also meant ignoring reporters who were staked out in the House office building where the Judiciary Committee worked – and who would pepper aides with questions when they went out for lunch.

“I particularly remember Sam Donaldson who had a really loud yell and he got to know the names of the lawyers, so he would yell, ‘Hillary, Hillary, come over here and talk to me.’ We would just walk by,” she recalled.

The no-leaking rule also went a long way, Clinton said, toward giving credibility to the House proceedings, which resulted in the Judiciary Committee’s passage of three articles of impeachment and Nixon’s resignation before the Senate could hold a trial.

“We did not know where this was going to end up. I certainly didn't. I didn't come into it with any preconceived notion that, OK, this is going to be easy. We're going to lay out all this stuff then the House will impeach and then he'll be convicted in the Senate. I certainly didn't do that. I don't know anybody who did. And because it was such a historic experience, we all felt the weight of that responsibility,” Clinton said. “And John made very clear that we would be betraying our duty as lawyers and our historic obligation if we talked.”

It’s a very different story in 2019, where both Democratic and GOP committee aides coming from their respective partisan silos provide reporters with background updates about the status of the Trump impeachment debate. At the same time, panel leaders including Judiciary Chairman Jerry Nadler and Intelligence Chair Adam Schiff, as well as rank-and-file lawmakers, frequently talk about the process on cable TV and social media.

During Watergate, Clinton said she made up her own mind while working on the House panel that there were some rough guidelines that lawmakers could follow as to what constitutes an impeachable offense.

“Once I had done the research it seemed clear to me that the president was not above the law,” she said. “The president did have certain authorities, certain standing. So it didn't require that there be a crime charged in order for there to be an impeachable offense. But what that impeachable offense was often keyed to what we think of as criminal behavior.”

“So obstruction of justice is a crime,” she added. “And whether a president is ever charged with obstruction of justice or not, the obstruction of an investigation can represent abuse of power that rises to the level of high crimes and misdemeanors and therefore be the basis of an article of impeachment.”

Clinton also acknowledged a debate in Congress during Watergate among fence-sitting House members who were skeptical of voting to impeach Nixon without a guarantee the Senate would back them up with a trial that convicted the president -- a point House Democratic leaders have emphasized this year about Trump, in an echo of the Nixon-era history, as they’ve sought to tamp-down pro-impeachment momentum within their own caucus.

“Well, I think that that's one way of looking at it and it certainly is defensible,” Clinton said. “But I think another way of looking at it is that if you are persuaded that the president has abused power, committed a high crime or misdemeanor then it's up to the proof that has to be presented in a trial to determine whether two-thirds of the Senate agrees with that. And remember the senators could bring whatever assessment they wanted to this determination. And you couldn't second guess that, you couldn't preempt that. It had to be left to them.”

Clinton said she wasn’t surprised by the House votes to impeach Nixon, noting the Judiciary panel chairman and staff “had a pretty fair idea of who was going to vote for it by then.” But she said she didn’t celebrate how the Nixon presidency came to its end.

“I was not at all happy or jubilant about him resigning,” Clinton said. “I thought it was a very sad chapter in our history. I thought the actual departure was a really poignant, painful moment for him and his family as well as for the country. So, I watched it on TV, like I guess everybody else did. And it was a really very unfortunate, sad outcome.”

All of that history, Clinton argued, got lost on House Republicans in 1998 when they advanced two counts of impeachment against her husband – for obstructing justice and lying under oath to a grand jury about his affair with the White House intern, Monica Lewinsky -- but then the Senate acquitted him.

“That lesson was not learned,” Clinton said. “And that's why I think it's important to keep talking about how serious this is. It should not be done for political partisan purposes. So, those who did it in the late 90s, those who talk about it now, should go back and study the painstaking approach that the [Watergate] impeachment inquiry staff took. And it was bipartisan. You had a bipartisan staff and you had both Democratic and Republican members of the committee reaching the same conclusions that there were grounds for impeachment.”

Clinton’s relatively minor role on the House Judiciary Committee has been the subject of fierce speculation for years -- including the debunked internet rumor that she was fired -- but she denied playing a role in the panel’s debate that Nixon was not entitled to his lawyer, James St. Clair, during the impeachment proceedings.

“I was not involved in that,” Clinton replied. “I knew about it. That was really among the senior lawyers led by Doar and the House members. And my memory is that they were very expansive in permitting St. Clair to be privy to information to be part of the process. But I don’t know any more details."