Hillary Clinton’s darkest days detailed in new book about White House staff

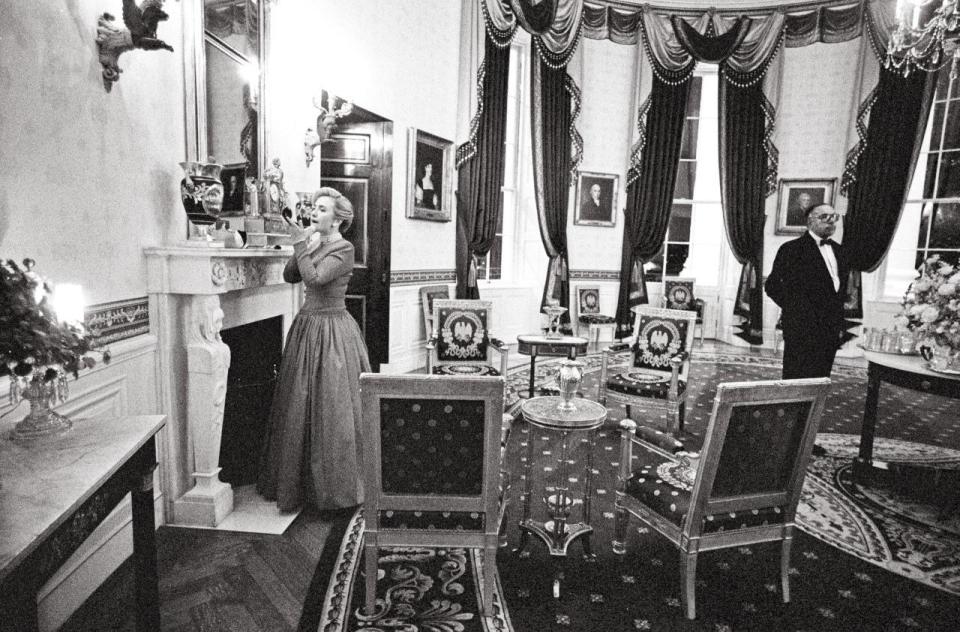

Hillary Clinton does a last-minute touchup in the Blue Room before the 1996 National Governors Association dinner as longtime butler James Jeffries stands nearby. (Photo: Barbara Kinney/White House, courtesy of William J. Clinton Presidential Library and Museum)

WASHINGTON — There is a recurring theme about the lives of presidents and their families in a new book about the things that White House residence staff have seen inside the most exclusive home in America over the past few decades.

Those living inside the White House live under such a microscope that during their lowest moments, it has been hard for them to find privacy inside their own home.

After returning from Dallas on the day John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, first lady Jackie Kennedy broke down crying only when in the confines of the elevator. There were two people with her: Bobby Kennedy, the president’s brother, and doorman Preston Bruce. The three of them clung to each other and wept.

It’s one of many stories in Kate Andersen Brower’s The Residence: Inside the Private World of the White House. Brower, a former White House correspondent for Bloomberg News with earlier stints at CBS News and Fox News, interviewed about three dozen former members of the most prestigious house staff in the world: the maids, chefs, florists and butlers who staffed the first family, going back to the Kennedys.

Eleven years after JFK’s tragic death, Richard Nixon broke down in tears on his last day in the White House, after resigning over the Watergate scandal. He was in the same elevator that Jackie Kennedy had wept in a decade earlier, gripping the arm of the same doorman, Bruce, who had grieved with Jackie and Bobby.

Brower’s book is a portrait of these men and women who have been background characters and firsthand observers to history. It’s also an intimate look at the private lives of the first families, with a lot of material about likely 2016 presidential candidate and former first lady Hillary Clinton.

Just as Jackie Kennedy was linked with Nixon by her brief, private moment of grief inside the White House elevator, Clinton is linked to him in the book by the vivid retelling of very similar lonely, forlorn walks that both of them took in their darkest days.

Moments after he resigned the presidency live on national television from the Oval Office, Nixon saw Bill Cliber, the chief White House electrician, walking along the outdoor colonnade that runs along the Rose Garden.

“Where you heading, Bill?” Nixon said.

“Back to the residence,” the electrician said.

“Walk with me,” Nixon said. Cliber recalled that he said a few words of encouragement and that Nixon’s eyes were “glassy” and he was on the verge of tears. They parted ways in the residence without speaking.

President Richard Nixon bids farewell to his Cabinet, aides, and staff on Aug. 9, 1974. (Photo: AP)

One August day 24 years later, in the summer of 1998, Worthington White, a residence usher, was approached by Hillary Clinton. It was the weekend, a few days before Bill Clinton would admit to the nation that he had lied about having sexual relations with intern Monica Lewinsky.

Clinton wanted to walk with White to the pool that day, but only with White. Normally a Secret Service agent would have walked ahead of her, but Clinton made it clear to White that she did not want to see anybody’s face but his, and did not want anybody but him to see hers: no security, no groundskeepers or other staff, and certainly no public tours.

“If anybody sees her, or she sees anybody, I’m going to get fired, I know it,” White told Clinton’s lead Secret Service agent. “And you probably will too.”

Clinton walked with White to the pool around noon wearing red reading glasses, without makeup or her hair done, and carrying a few books. “She seemed heartbroken” to White, writes Brower. She spent three and a half hours at the pool, and returned with White to the elevator the very same way she had come: alone and unseen by anyone except for the usher and the agent trailing her. At the elevator, she turned to White, took his hands and squeezed them, looked him in the eye, and thanked him.

But the Clintons come in for mostly rough treatment in the interviews that Brower conducted with staff.

“They were about the most paranoid people I’d ever seen in my life,” said James W.F. “Skip” Allen, an usher from 1979 to 2004.

Cliber, the head electrician, told Brower that he had participated in nine Inauguration Day transitions between presidents, and that moving the Clintons into the White House “was by far the most difficult.” Cliber cited Hillary Clinton’s demand that he rehang seven chandeliers at once as an example of what he said were unreasonable demands.

Allen said, in Brower’s words, that “the Clinton’s preoccupation with secrecy made relations with the staff ‘chaotic’ for their entire eight years in office.” Florist Wendy Elsasser said the Clintons had a “standoffish” relationship with the staff and attributed it, in part, to their concern over their daughter Chelsea’s privacy.

But in a perhaps telling precursor to Hillary’s decision as secretary of state to operate using her own private email system, the Clintons changed the phone system in the White House because they thought, according to Allen, that “too many people could listen in on them” under the old operator-run phone system.

“So they had all the White House phones changed over to interior circuitry so that if the first lady was in the bedroom and the president was in the study, she could ring him from room to room without going through the operator,” Brower writes.

There are also stories of the Clintons up in the middle of the night in the White House, apparently unable to sleep and rearranging furniture to occupy themselves, and complaints from the kitchen staff that the Clintons never told them when they wanted to eat or how many people the staff should cook for. George H.W. Bush’s family, the staff told Brower, always communicated these details to the kitchen.

There are numerous contrasts between how the H.W. Bush family and the Clintons treated the domestic staff that are unflattering to the latter. Bush often played horseshoes with the staff, and one time, he asked someone for bug spray. “The worker had sprayed the president from head to toe before he realized he’d accidentally used a container of industrial strength pesticide,” Brower writes.

Bush’s face quickly turned red, and he had to be rushed to the showers to be washed off. But Bush reportedly took the incident in stride and good humor, and, rather than throwing a tantrum, joked about needing to get back to the horseshoe tournament.

But Hillary and Bill don’t come off as badly in the book as former President Lyndon Baines Johnson and former first lady Nancy Reagan.

Reagan was “spoiled rotten” said florist Ronn Payne.

Many of the staff were terrified of President Ronald Reagan’s wife. “I never wanted to be on the wrong side of her,” said Elsasser.

And LBJ, well, he comes off as a monster. He harassed residence staff for years to construct him a specialized shower to replicate the one he had at his private Washington home, with “water charging out of multiple nozzles in every direction with needlelike intensity and a hugely powerful force.”

“One nozzle was pointed directly at the president’s penis, which he nicknamed ‘Jumbo.’ Another shot right up his rear,” Brower writes. Johnson, who traveled with his own special shower nozzle, wanted the water pressure at the White House to be “the equivalent of a fire hose, and he wanted a simple switch to change the temperature from hot to cold immediately. Never warm.”

Johnson harangued the staff when they explained to him that they would have to lay new pipe, install multiple new pumps and increase the size of the water lines to the White House to create this shower contraption.

“If I can move 10,000 troops in a day, you can certainly fix the bathroom any way I want it!” Johnson yelled at the staff, according to Brower.

Reds Arrington, the plumbing foreman at the White House, spent five years trying to perfect the project, and at one point was hospitalized with a nervous breakdown. The staff went through five different replacement shower models. LBJ eventually got something like what he wanted, sort of. The water temperature was so hot that the steam it emitted “regularly set off the fire alarm,” Brower writes.

Near the end of his presidency, LBJ told Arrington that the shower was his “delight.”

Not long after, Nixon took over the White House. He took one look at LBJ’s elaborate shower setup and muttered, “Get rid of this stuff.”

Kate Andersen Brower, author of The Residence: Inside the Private World of the White House. (Photo: Pete Williams)