Heroin Killed My Parents

In September, a photo of an Ohio couple who’d overdosed on heroin with a little boy in the backseat of their car went viral. Americans shuddered at the image of the driver and woman in the passenger seat - the boy's grandmother, who had custody of him - unconscious, heads lolled back, while the boy sat in his car seat behind them. The off-duty police officer who found the couple called an ambulance when the grandmother started turning blue. Authorities later placed the boy with other relatives.

According to the Partnership for Drug-Free Kids, the nation’s heroin epidemic has led to a drastic rise in the number of kids placed in foster care over the last few years. The Public Children Services Association of Ohio found that 70 percent of children less than a year old who were placed in foster care in that state in 2013 had parents using heroin or cocaine.

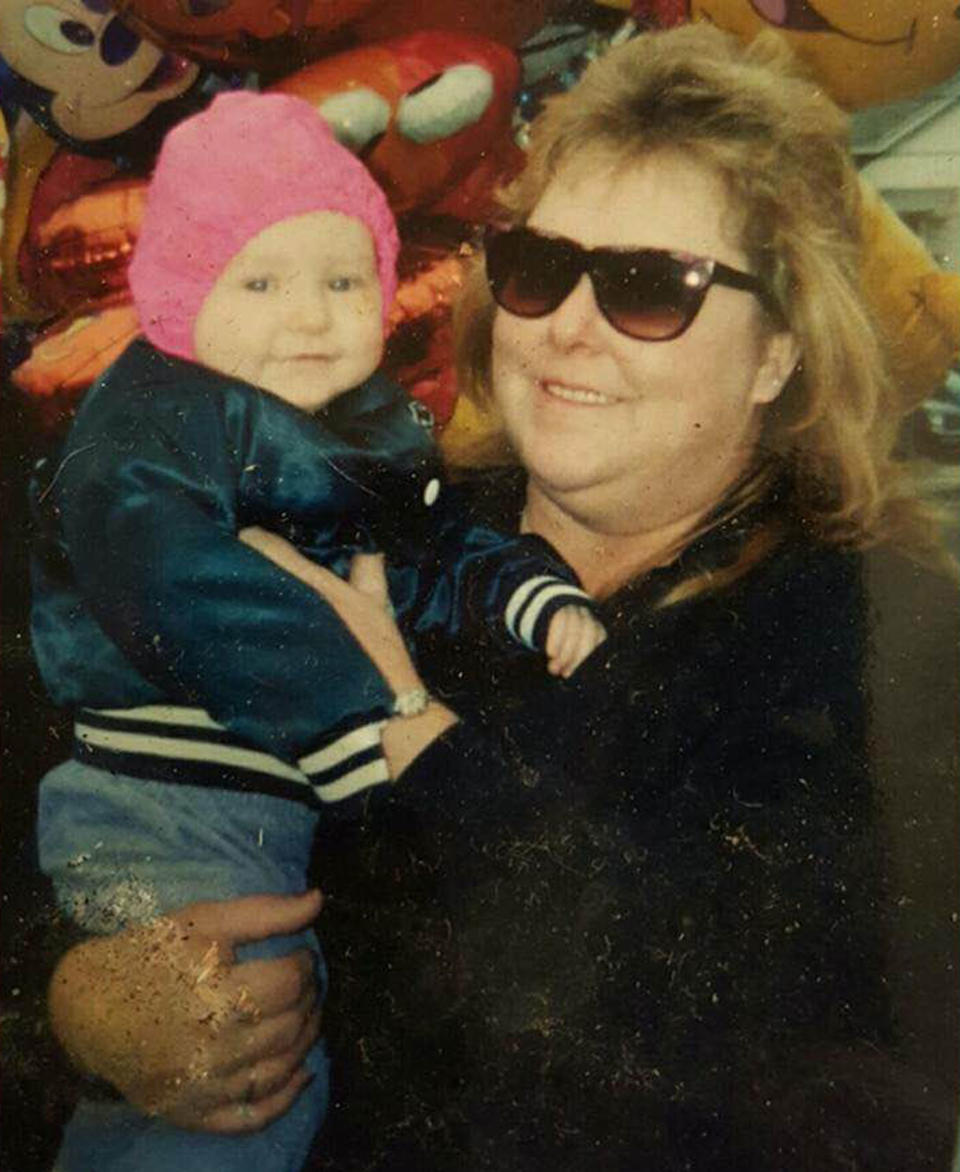

Kellie Myers, 20, a nursing assistant from Quakertown, Pennsylvania, grew up with a mother addicted to heroin. This is her story.

I never thought that I’d be 20 years old and parentless. Some of my friends think it’s cool that I can do whatever I want, but it’s not. My parents left so much behind. When I see these videos and photos of parents getting high with their kids around, I get livid. I’d love to ask these parents if it’s worth it. That’s what I’d ask my mother, if I could: “Was it worth it?”

My mom had a troubled past. She dropped out of high school, ran away from home, drank and partied pretty heavily with cocaine. But when she found out she was pregnant with me, she stopped. She wanted me more than anything. When I was born, she said, I was the light of her life.

Things started to change around the time I was 6 or 7 years old. My mom was a certified nursing assistant and she hurt her back while moving a patient on the job, got surgery, and became addicted to painkillers. I got used to her nodding out, or sliding off chairs and onto the floor, lifeless. My father used to explain her behavior away: “Mom doesn’t feel good,” he said. But I worried about what was wrong with her; I was confused and scared.

By the time I was 10 years old, I knew what was going on. Other kids’ parents didn’t act that way. She skipped my school events, and I started acting out, hitting other students and pretending to be dumb in class, so I could spend more time with my teachers. She wrecked 10 cars over the years when she was driving under the influence - one time with me in the passenger seat. She told my dad later that I had been trying to show her my Happy Meal toy and distracted her. I hurt my leg in the wreck and had to spend the night in the hospital. But instead of worrying over me, my mom played it down. “It wasn’t that bad, Kellie,” she said. “Stop making such a big deal of it.” I took it to heart. I really believed I’d caused the accident.

My mom started shooting heroin when I was in high school. She was diabetic and used needles for her insulin, and then started using them to shoot up. I could tell when my mom was on heroin because her highs seemed more intense. When I was 11th grade, she was in the bathroom one day for a long time, supposedly showering. When she wouldn’t come out, my dad threatened to kick in the door. I picked the lock with a pin and found my mother naked, folded in a ball, with a needle in her arm. Heroin baggies were floating in the toilet water. That’s one of those images I’ll never be able to get out of my head

Sometimes she embarrassed me. When I was about 14, I had a friend from my softball team over for dinner and my mom got so high, she fell asleep at the table with one hand holding the newspaper, the other holding a forkful of sausage. My friend was scared, and I was so angry. I worried my friend would tell her parents and I’d never see her again, or that she’d tell our teammates. She and I never talked about it, and she never came over again.

Like lots of addicts, my mom was in denial. She didn’t think I understood what she was doing. But I saw things. I found her once with blue lips, barely breathing, and had to call 911. She ended up on life support for a week - but when she woke up, she pretended nothing was wrong. “I didn’t OD,” she said, dismissing me and my father. I knew she was trying to manipulate me again. What I still didn’t realize, though, for some reason, was that she might die from her addiction.

My mother hurt me and my father. She’d say she did drugs because I drove her crazy, which devastated me. Sometimes I’d lock myself in my room and cry or spend the day calling my dad, saying, “Please, I need you.” He did his very best to shield me. He wanted to give me the best life possible and he tried so hard. He surprised me with my first car, came to all of my softball games, helped me pick out my prom dresses. As I got older, he’d tell me how much he loved my mom. When they met, she was full of life, funny, with a big laugh. She took care of his children from his first marriage as if they were her own. He always hoped that she’d turn back into the person he’d fallen in love with. He did so much for her - took her where she needed to go, made sure she had money, groceries. She loved him too, I think. Although I could never be sure if she loved him for him or loved him for what he did for her.

In 2014, my dad grew deeply depressed. The first time I realized how sick he was in October that year, before my senior night [of high school], when the seniors and their parents go out onto the field at halftime during the football game to be recognized by the school. I was in the marching band and the color guard, and my dad always went to my Friday night games. We’d sent invitations out to a bunch of my relatives. But when the day arrived, my dad said he didn’t feel good. “Dad,” I pleaded, “come on. It’s my senior night.” He ended up going, but in photos from that night, you can tell he’s off. It’s like he’s looking through the camera, through the photographer, into the distance.

The next morning I woke up to find him crying hysterically. “I can’t do this anymore, Kellie,” he said. “I want to drive the car off the bridge.” I was terrified, worried he might hurt himself or both of us. Just then - thank god - my grandparents happened to knock on the door. We rushed him to the hospital together, and he stayed in the psych ward for two weeks. My world felt like it was crashing down.

In December 2014, the day after my parents’ wedding anniversary, my dad nearly died. When he didn’t go to work on time that morning, I ran to his bedroom and found him in a pool of sweat, with vomit everywhere. He’d taken a 90-day supply of multiple medications. I started crying, screaming for my grandparents to call 911. He was in a coma for a week. After he got out of the hospital, he would stay up all night, pacing. “I can’t do this, Kellie,” he would say, over and over. “I can’t.”

The months of his depression were a roller coaster. I bounced between the hope that I’d get my old dad back and feelings of extreme anxiety. My grades began to suffer. Every day I feared my father would go to work and never come home.

In the end, I couldn’t help him. A few weeks after Christmas, in January 2015, my dad killed himself.

I was in class when I got called to the principal’s office at school. My step-grandmother was there, crying silently, holding a box of tissues. “Is he dead?” I asked. She nodded slowly. I lost my shit. “Who’s going to walk me down the aisle?” I was howling, bawling.

The days after that were a blur. His death would play back in my dreams and I’d wake up, screaming. My mom seemed to be grieving too. My family and I believed my dad had done what he had done to wake her up. I think he thought this was the only thing that might convince her.

But within weeks, my mother was hanging out with bad people again. Without my dad to look after her, she spiraled fast. When she was high on heroin, I would take videos of her rocking back and forth, flailing, to show my friends and family that I wasn’t lying, that these episodes weren’t the result of side effects from her pain medication.

One day I gave her an ultimatum: “Mom, I’m going to call 911 and you’re going to get clean, or I’m not going to be in your life anymore,” I said.

She ignored me, nodding out.

“Do you even want me in your life?” I asked.

“No, I don’t,” she said. And that was it. I walked away. It’s hard to admit it, but I’d gotten to the point that I just didn’t care anymore about what happened to her.

Still, I didn't expect to lose her so soon. The very next day, I was out shopping with a friend when my vice principal called out of the blue and asked me to come to school. He wouldn’t say what for. But I had a feeling it was about my mother.

My step-grandmother, vice principal, and guidance counselor were waiting for me when I got there. A few minutes after I arrived, an unfamiliar number popped up on my phone. It was a doctor. My mom had overdosed, been rushed to the hospital, and died.

"It's over, Kellie," my guidance counselor said, wrapping me in his arms as I shook. "It's over."

I couldn't believe it. Four months and three weeks to the day my father passed away, my mom was gone too.

My mother's death certificate says she died of natural causes, which is ridiculous. Her bloodwork showed she had taken four different muscle relaxers, Adderall, Dilaudid, and a medicine usually used for anorexics. They called it a natural death because there wasn’t enough of any one of the drugs in her system to have killed her on its own. That’s crazy. There were 15 different medications in her body. My mother was an addict who overdosed. It should say that.

That was a year and a half ago. I graduated high school and am a nursing assistant now, like my mom was. My goal is to become a trauma nurse or work in the neonatal intensive care unit. I want to devote my life to taking care of people.

To this day, I’ve never touched drugs, and I don’t plan on it. I’ve wanted to see a therapist to get medication for my anxiety and depression. I don’t laugh or smile like I used to, I pick my fingernails until they bleed, and I’ve struggled over the years with my self-image and my relationships. I’ll go from boyfriend to boyfriend, thinking that if a guy loved me, it would change everything. But I’m so worried about medications’ side effects - like, for example, suicidal thoughts - that I haven’t gone to the doctor. I don’t drink much either. I’m terrified of getting addicted.

Do I forgive my mom? Yes and no. Some days, I feel forgiveness, but on the others, when I get flashbacks, I blame her. My mother killed two people with her addiction, herself and my father. I don’t know if I’ll get over that.

People want to know what it’s like to be the child of an addict. All I can say is it’s like feeling helpless, powerless, in every way possible all the time, even when it comes to decisions you think you’re making for yourself. For years, I felt like I was drowning in my life, despite doing everything in my power to change it for the better. I still feel that way sometimes. The choices my parents made still affect me. My friends are going to college, pursuing different opportunities - but I have to work 24/7 to support myself because my parents aren’t here. It’s hard not to resent that.

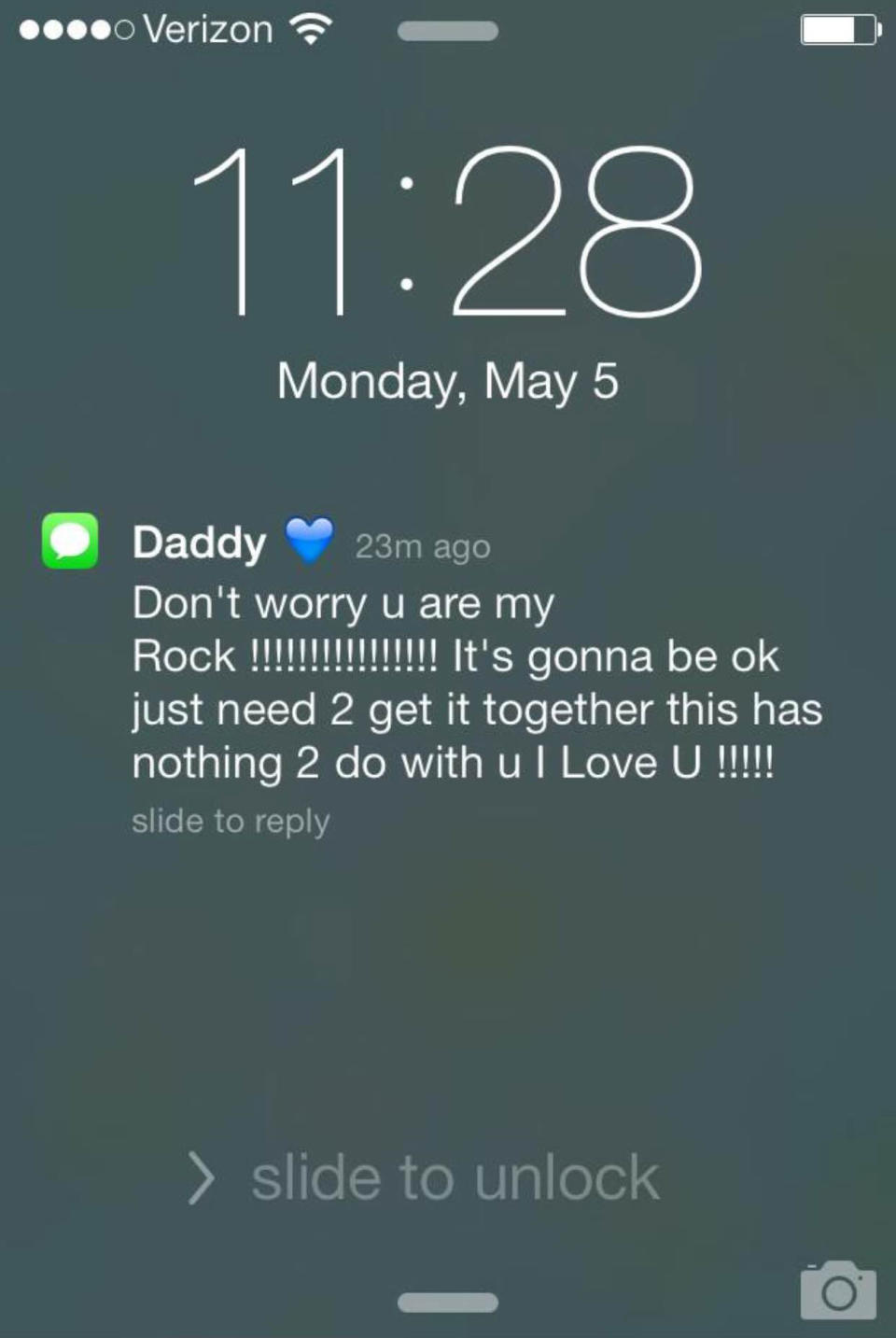

My father was my rock - I miss him so much. I’ll never forget my high school graduation. It happened a week after my mom died. My best friends organized a text that went schoolwide about cheering for me, and when my name was called, I got a standing ovation. I received my diploma onstage with both of my grandmothers. Everyone was crying except for me. I didn’t shed a tear.

I was happy. Because I knew for sure that my dad would’ve been proud.

To read the story of a mother who was addicted to heroin while parenting her two young children, click here.

If you or someone you know needs help for addiction, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) or visit the online treatment locators.

Follow Kristen on Twitter.

You Might Also Like