Here's what the stock market did during Watergate — and why

Everyone these days seems to have one word on the tip of their tongues: Watergate.

In the 1970s, the U.S. stock market endured one of the longest and most brutal bear markets in its history. After the Dow nearly topped 1,000 — topping out at 990 — for the first time in 1966, it would not regain this level on a closing basis until 1982. It would never trade below that level again.

In 1979, BusinessWeek famously published its cover declaring the “Death of Equities.” Inflation was running in double-digits while unemployment rose as “stagflation” riddled the economy.

In the months around Watergate, there was certainly political turmoil for investors to worry about, but the economic headwinds were far more problematic for the stock market, which endured one of its worst stretches in history.

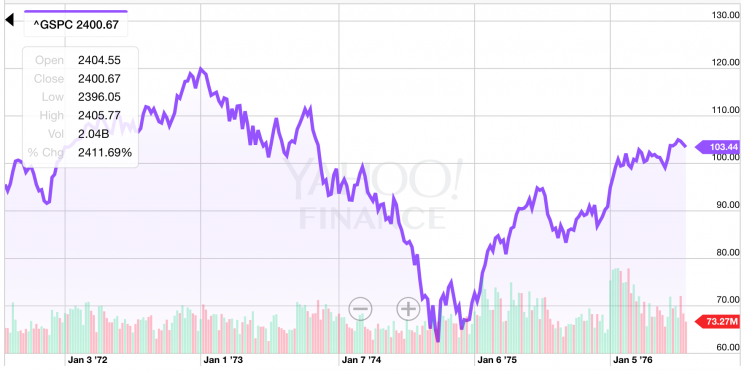

From the start of 1973 through Nixon’s resignation in August 1974, the S&P 500 fell about 50%.

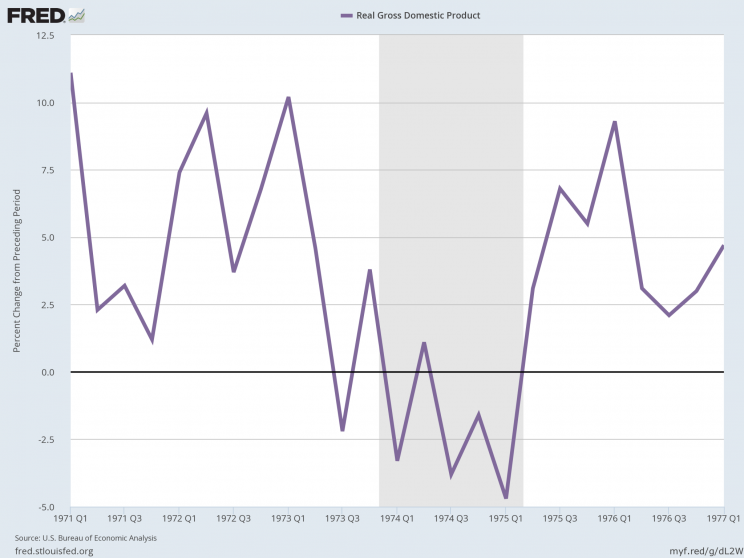

During this period, the economy was on its way into recession. After economic growth hit an annualized rate of 10.2% in the first quarter of 1973, economic growth rates hit -3.3% in the first quarter of 1974 as the economy entered a recession from which it did not emerge until the second quarter of 1975.

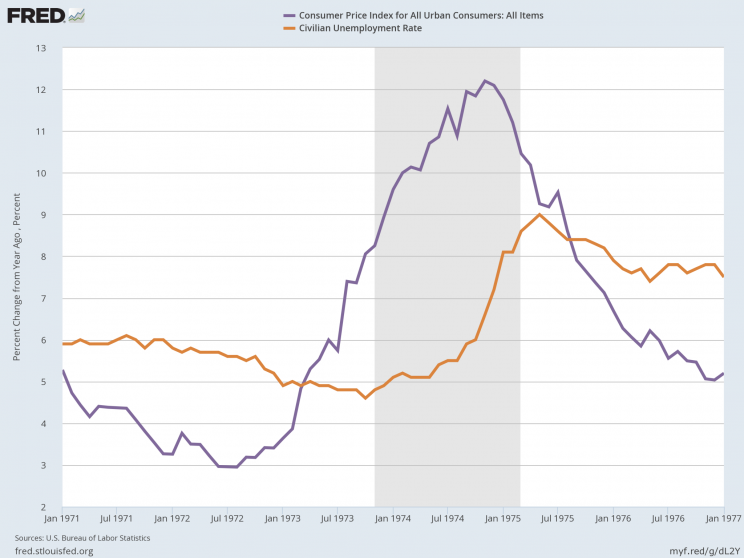

Inflation, meanwhile, was running in the double-digits. Consumer prices rose 3.6% from the prior year in January 1973. One year later, inflation was running at 9.6% year-on-year; by November 1974, inflation was up 12% year-on-year. Unemployment, meanwhile rose throughout 1974, eventually hitting 9% by May 1975.

Oil prices, meanwhile, rose from $3.56 a gallon in January 1973 to $10.11 a year later as OPEC members imposed an oil embargo against the U.S. in response to U.S. involvement in the Arab-Israeli War. Adjusted for inflation, this sent oil prices from about $20 a barrel to north of $50.

Following The New York Times’ Tuesday evening report that President Donald Trump asked former FBI director James Comey to end an inquiry into ties former national security advisor Michael Flynn had to Russia, investors are wondering when the chaotic headlines coming from the White House will stop.

And this report comes just a day after The Washington Post reported Trump revealed “highly classified” information to Russia’s foreign minister. On Wednesday morning, The Wall Street Journal editorial board wrote an op-ed criticizing Trump for this latest series of reports, which puts his actual agenda on things like tax reform and infrastructure in danger of never coming to fruition.

And all this has investors looking back at history to figure out what might happen next for a stock market that has hardly reacted to any of the latest turmoil in Washington, D.C. In the early days of the Trump era, the stock market’s reaction to chaos in Washington, D.C. has been defined by one thing: indifference.

Volatility has been low. Stock prices are at record highs. And while investors see U.S. stocks as overvalued, the reaction to headlines that seem politically perilous has been non-existent.

On Tuesday evening, U.S. stock futures did sell off modestly, with S&P 500 futures falling about 0.4% and Dow futures losing 100 points.

As analysts at Bespoke Investment Group pointed out in a note on Wednesday, “That’s not a big move, but is relative to recent moves, and is a departure from recent Trump administration dust-ups that were summarily ignored by the market.”

In its note, Bespoke also makes a really important point about how political risk, if it does come to markets at all, is likely to make itself felt: slowly, and then all at once.

“We would also like to make the point that for US markets, the awareness that political risks exist will be slow to build then take place all at once, if it ever does,” the firm writes. “That’s the template for how most human beings adapt to big changes in ‘established fact.'”

But as Bespoke notes, just because stocks may eventually sell-off in reaction to a series of Trump-related headlines this doesn’t mean an outright bet against the U.S. stock market is a good risk-reward because “predicting when and if [a sell-off comes] is not easy work.”

—

Myles Udland is a writer at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter @MylesUdland

Read more from Myles here: