Helping others recover from errors is how he kept vow to not let mom down again | Opinion

Ten years. That’s how long in prison Ruben Gaona received for his role in a drug ring that transported cocaine and marijuana from Texas to Milwaukee in March 2010.

Gaona grew up in El Paso to a single mom and five siblings. His father was both mentally and physically abusive to his mother. One time, his father broke into his bedroom window with a gun and threatened to kill the entire family.

“We called 9-1-1 on him. After that, my mom knew she had to leave him,” Gaona said.

His mother, Maria Reyes, relocated the family to Milwaukee’s south side in June 1996, making the trek on a Greyhound bus. Gaona was 15.

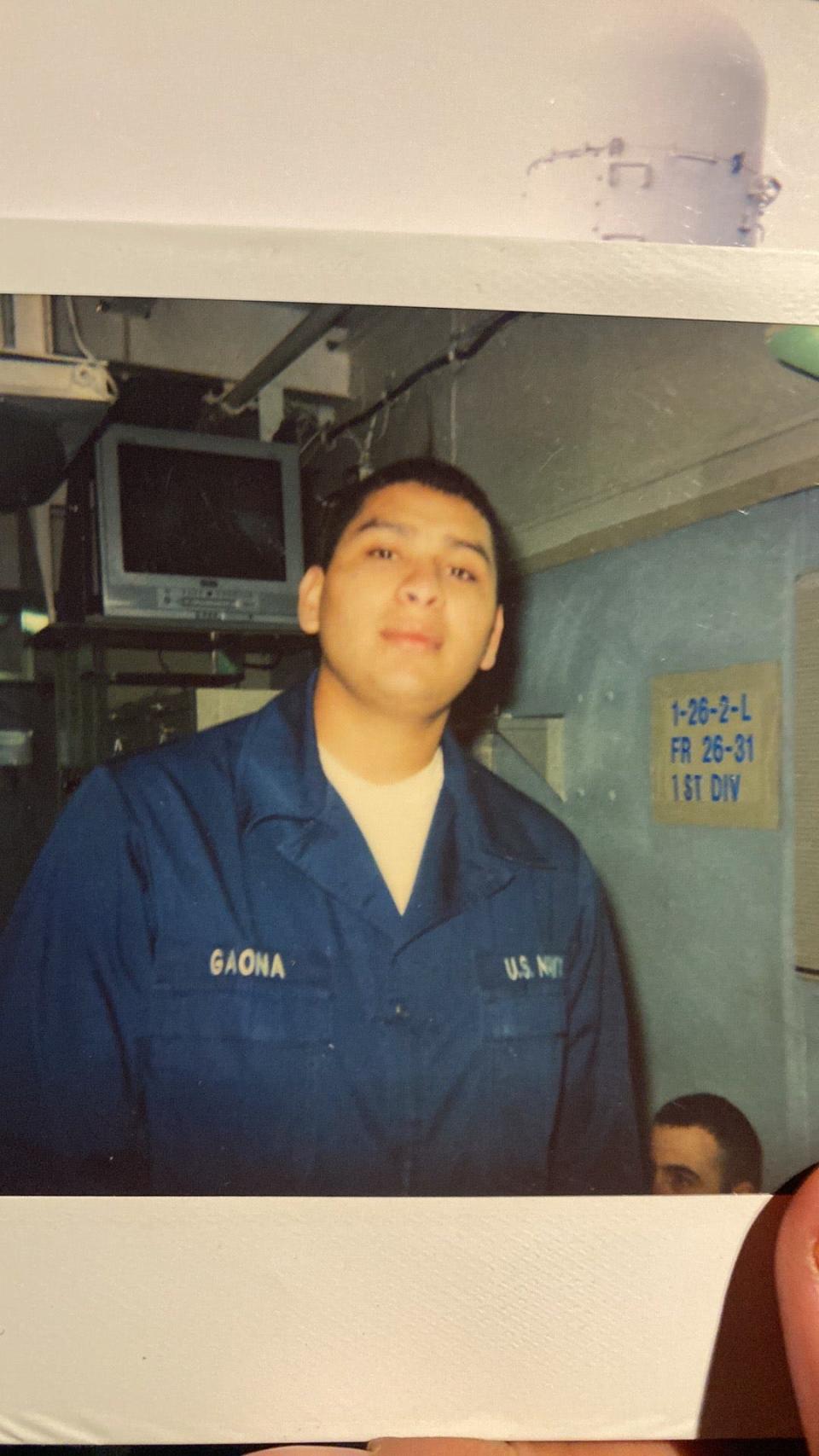

During his senior year at Pulaski High School 1999, Gaona received life-changing news: he would be a father. Faced with limited job options, Gaona decided to join the U.S. Navy for the direction he needed.

At first, everything seemed to be going well. The Navy provided a meaningful alternative to what he’d seen growing up. He quickly developed a passion for it, but 45 days before he was set to reenlist, he was told he couldn't because of a back injury.

The Navy determined Gaona was unfit for sea. He received an honorable discharge and was back on Milwaukee’s south side. That’s when he made the dumbest decision of his life. On March 17, 2010, Gaona was one of 17 defendants charged in a drug conspiracy and money laundering case. Several of his siblings were also involved.

Despite receiving monthly visits from his family and communicating with them through letters and phone calls, the absence of their physical presence was deeply felt. Nonetheless, his mother remained a stalwart source of support.

Twice a month, Reyes drove Gaona's wife and kids nearly six hours to visit him in prison. Their unwavering support was crucial for Gaona, as it helped him get through tough times. However, not all prisoners are fortunate enough to have someone to support them, leading many to re-offend once they are released.

Gaona made a promise to his mother that he would never let her down again. Nearly 13 years later, he has dedicated himself to helping people who were once in prison. His non-profit organization, My Way Out, has been successful in keeping more than 600 people out of prison by providing essential services such as housing, employment, and transportation. The program has a 90% success rate.

Some leave prison with only the clothes on their backs

The effort began as thousands of prisoners were being released early from state and federal prisons to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Many were released with just the clothing they came with and without a solid reintegration plan to avoid going back to prison.

My Way Out offers support for things that may not be apparent to most of us. For instance, when a client needed a winter coat, Gaona's team purchased a new one for the man. When another landed a job but needed reliable transportation, the team bought the man a 10-speed bike.

Gaona, 42, said since his team doesn’t have office space, they can meet the client where they are.

“If someone calls me right now, I ask them where they are and go to them to make it easier. We do a lot of meetings in coffee shops and the library,” he said. “It’s hard enough for them; we don’t want to make it more difficult.”

Watch: For more on the program, see James Causey's interview of Ruben Gaona on Black Nouveau

If they cannot provide needed services, they collaborate with other reentry programs to ensure clients receive what they need. The program operates on donations from organizations such as the United Way, Greater Milwaukee Foundation, Bader Philanthropies, Milwaukee Bucks Foundation, Roots & Wings, and others.

More than 70% of the clients served are African American or Hispanic. Anthony Dodd, assistant superintendent at County Community Reintegration Center, called the program a valuable safety net. Addressing stable housing and employment are critical to the success of men and women, and Gaona has helped hundreds in this area.

Dodd said after a person has served their time, there needs to be a higher level of forgiveness and second chances. Approximately 95% of state prisoners will be released at some point, with 80% placed under parole supervision.

Many people don't consider public safety in terms of ensuring that formerly incarcerated individuals have access to stable housing, good jobs, and transportation. However, Dodd said these factors are crucial in reducing recidivism rates.

It is more cost-effective to invest resources to support individuals in becoming productive members of society rather than spending approximately $40,000 per year to incarcerate them again. Milwaukee County Chief Judge Carl Ashley agreed.

There are still many individuals in our society who hold the belief that if someone makes a mistake, they do not deserve a second chance, even after they have paid their debt to society. This kind of thinking makes it even more challenging for people to secure housing and employment opportunities, Ashley said.

“My Way Out is an opportunity for those who know when you get out of your time. There are people here who will lift you. We need more programs like this,” he said.

Brewers tickets create lasting memories for father and son

My Way Out stands out from other reentry organizations because all its employees have been incarcerated. Frank Harris Sr., 63, felt out of touch with technology after serving 26 years in prison for homicide. My Way Out employees helped him overcome his fears.

“They truly understand what you are going through and don’t hold your hands," Harris said, "They know how to talk to you because they have been in the same place."

When Harris was incarcerated, his son was only 14 years old. One thing he always wanted to do was take him to a Brewers’ baseball game.

My Way Out gave him that opportunity once he was released by providing him with two tickets to see the Brewers play at American Family Field. Frank Harris Jr., 44, said it was an experience he would never forget.

“I’ve been to a baseball game before. I’ve just never been with my dad. It was a perfect day. I don’t even remember who won the game. I know that I enjoyed that time with my dad,” Harris Jr. said.

Since the game, Harris Jr. also treated his dad to a first-round Milwaukee Bucks playoff game at the Fiserv.

"It's tough of people after they are released. It's harder when you don't have a stable support system. That's why so many people end up going back. Programs like My Way Out gives people hope so they can get back on track," Harris Jr. said.

At an event held at Bader Philanthropies in January, Harris Sr. and other individuals shared their positive experiences with the organization.

One man spoke about how the organization provided him and his son with safe housing, while another thanked Gaona for always being available to provide assistance, regardless of the time of day. Another shared how the staff helped him find employment, which ultimately led to him landing a better job as a barber.

During his speech, Gaona shared a quote he had written down five years into his sentence that changed his life. He now lives by theses words, "I can't does not exist, as it is merely an excuse, we tell ourselves to avoid reaching our full potential."

Gaona’s story mirrors that of many clients he serves today, but he wants them to know that they have the power to create a new reflection.

Reach James E. Causey at jcausey@jrn.com; follow him on X@jecausey.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Program helps former prisoners overcome barriers when sentences over