Here’s how you can help dolphins off South Carolina’s coast - and learn more about them

For one day each year, hundreds of people are purposely stationed around Charleston’s peninsula.

Every person’s unwavering gaze scans the horizon. They’re all watching with one goal in mind: to tally the number of dolphins cruising local waters. It’s the annual dolphin count, and this year’s will be held on April 20.

Five years ago, the North Charleston-based nonprofit Lowcountry Marine Mammal Network held its first count, thinking it’d be a novel way to teach the community about Lowcountry dolphins, their health, their behaviors and the overall status of the mammals.

In 2023, weather dampened the event, which Lauren Rust, the nonprofit’s founder and executive director, said made the count lower than normal. Seventy-four dolphins were spotted. Typically, over 100 dolphins are recorded by participants, or what Rust calls “community scientists.”

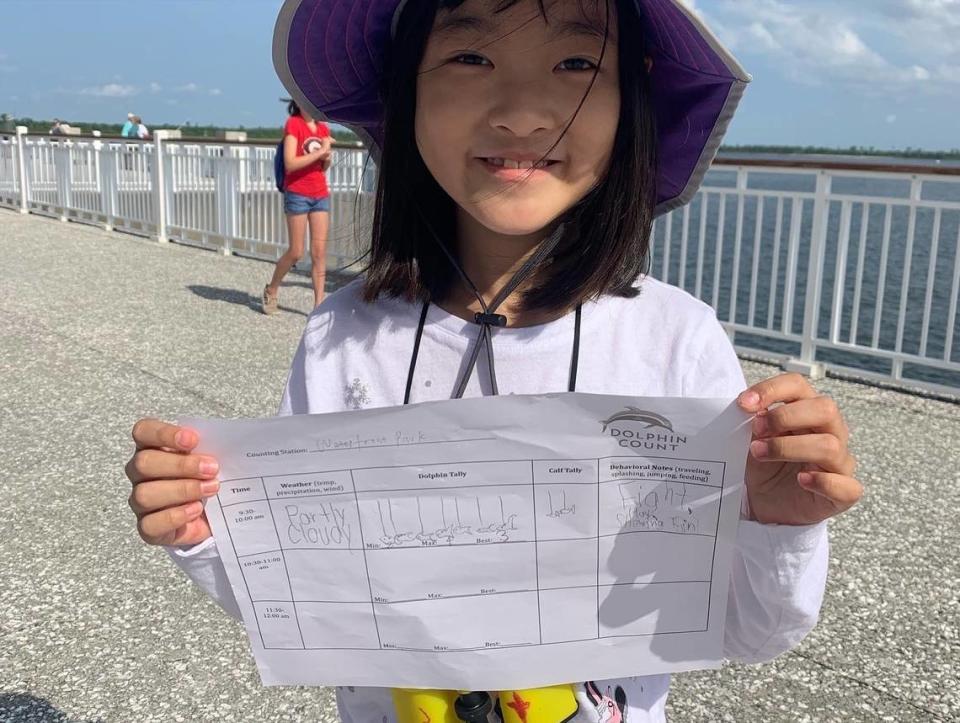

Spread across 13 sites around Charleston’s peninsula, the count is done three times at each site in 30-minute watching intervals. In total, between 450 and 500 participants will fill out a single piece of paper with four simple questions: Dolphin tally? Calf count? Behavioral notes? Weather conditions?

What about dolphin double-counting? Because the sites are a mile away from each other and with 30 minutes lapsing from the first count to the second, a dolphin would have to be hauling it pretty fast to be counted at another site. It’s not unlikely, Rust said, but the distance and the 30-minute interval decreases the chances of double-counting.

Albeit straightforward and on a single day each year, the accumulated information from over 400 people provided the network with a crucial snapshot of the dolphin population and the community with a data-collecting opportunity.

While it’s not an exact science, Rust says the count reveals information about the dolphins in Charleston’s waters that the network wouldn’t have without the help of hundreds of watchful eyes.

From site to site and hour to hour, the dolphins’ routines become more evident. They seem to fancy the Sullivan’s Island site for feeding. And they’ll travel through Mount Pleasant as a gateway to other locations. Two years ago, a more grim site came into focus during the count — a mother pushing around its dead calf. The network was able to pull the calf from the water and collect samples for deeper data points, like cause of death.

The story is the harsh reality of what dolphins face while swimming around a port city. The sleek mammals can get entangled or caught in crab pots, a threat that Rust said has been increasing in South Carolina over the past few years. Human interaction, water contaminants like microplastics, and disease are also common causes of death.

There are about 300 dolphins in Charleston, a number Rust said has stayed relatively stable. About 50 to 60 marine mammals, 80% of which are bottlenose dolphins, wash up on South Carolina beaches each year. About 98% of those stranded dolphins are found dead, Rust said.

In order to think on a macro level about how to protect dolphins in the Southeast, it has to start at a micro level. And the Charleston dolphin count is just that.

The network relies on the public to notify authorities “if they see a dolphin in distress or entangled,” Rust said. The dolphin count is one way to educate people on steps to take if they come across a sick, injured or dead dolphin. The dolphin count also reinforces the importance of decreasing single-use plastic bags and participating in litter sweeps to keep local waters clean.

Lowcountry Marine Mammal Network’s next dolphin count is from 9 a.m. to noon on Saturday, April 20. Sign-up is coming soon and can be accessed at https://www.lowcountrymarinemammalnetwork.org/.

For those who can’t make it out, a free app “Dolphin Count” allows for real-time dolphin spotting. The network maps the data quarterly and shares it to the nonprofit’s website.

To report a stranded marine mammal call 800-922-5431