Happy Birthday, Alan Greenspan: The Housing Bubble Wasn't Your Fault

The legendary Fed chair turns 86 this week, which gives us a moment to reflect on the most misunderstood piece of his legacy: Maestro's roll in the real estate bubble

There's one unassailable rule when it comes to writing about the housing bubble: you must criticize Alan Greenspan for keeping interest rates "too low for too long." Once you get past this ritual invocation, you can talk about whatever else you'd like, whether it's securitization, too lax regulation, or even Fannie Mae. But first: toolowfortoolong!

But what if the unassailable rule is wrong?

The conventional wisdom goes something like this. In 2003, Greenspan cut the benchmark interest rate to 1 percent, and was too slow to begin hiking. Lulled by historically low mortgage rates, home-buyers took on way more house than they could afford. Prices, of course, went into the stratosphere. By the time Greenspan belatedly raised rates to 5.25 percent in 2006, the damage was already done.

So it seems clear that we can blame the artist-formerly-known-as-the-Maestro, right? Well, wait a second. While it's undeniable that rock-bottom mortgage rates -- at least rock-bottom for the pre-2009 world -- helped fuel the subprime frenzy, it's not true that these low rates meant monetary policy was excessively loose. That's a common fallacy when it comes to the Fed: low rates do not necessarily mean policy is easy, nor do high rates necessarily mean that it is hard.

Nobody thinks the Fed ran a tight policy in the 1970s. And with good reason. Inflation spiraled out of control throughout the decade, despite interest rates that would qualify as exorbitant today. Compare that to our situation now. Rates are currently barely hovering above zero, yet inflation remains subdued. (No, really). As Ben Bernanke would tell you, looking at interest rates alone can be a misleading guide to the Fed's stance.

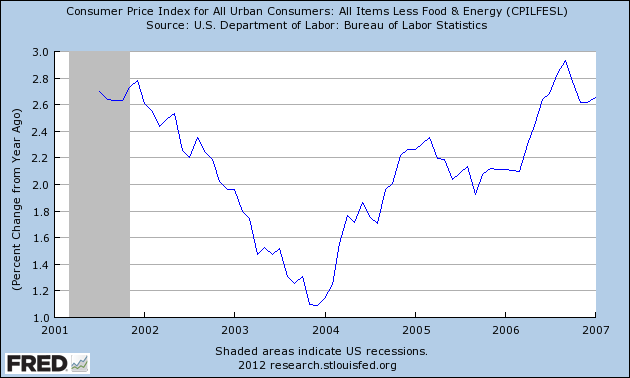

Bernanke said this back in 2003. The future Fed governor explained that inflation and nominal GDP -- which just refers to the total size of the economy -- are the best indicators for monetary policy. And looking at them totally vindicates Greenspan's low-interest rates in the 2000s. Here's a look at core inflation from that period. (Remember: the point of excluding food and energy costs from inflation measures is that those prices are set in world markets, and are highly volatile).

If Greenspan's policy had been wildly inappropriate, inflation should have shot up like a rocket. Instead, after flirting with deflation in 2003, prices settled within shouting distance of the Fed's then-unofficial 2 percent inflation target. Nominal GDP tells the same story. The Fed basically had interest rates where they belonged, even though -- huge caveat -- housing prices went up by an epic amount.

Wait. If Greenspan isn't to blame for the housing bubble, then who is? Don't worry, I won't blame Time's 2006 Person of the Year. Alan Greenspan is still to blame. Just not for the reason most people think.

Where the Fed really failed was as a regulator. It could have gone after the predatory lending in the subprime world, if it had wanted to. At least one Fed governor suggested doing so. Greenspan rebuffed him. Counter-factuals are always tricky, but if the Fed had clamped down on the endemic fraud in the mortgage market, it's not difficult to imagine the run-up in housing prices being much more muted. After all, if the problem had been low interest rates, prices should have skyrocketed across the board. That prices only skyrocketed for housing tells us that something peculiar was going on there, namely an abdication of any regulatory oversight.

On that note, I think we owe Greenspan a happy (belated) birthday. He's gotten a bad rap the past few years for his failings as a central banker, and that's just unfair. It should be about his failings as a regulator.

Source: Reuters

More From The Atlantic