What Happened to La Biennale Paris?

At the 29th edition of La Biennale Paris, formerly La Biennale des Antiquaires, which ended its eight-day run on September 17, the art and antiques enticed as always. The setting for the august French fair, the Belle Époque soufflé of glass and iron that is the Grand Palais, dazzled. Selections from Geneva's family-owned Musée Barbier-Mueller were displayed in a special exhibition that defined connoisseurship at its most thrillingly catholic. (Imagine a Bertoia chair, a Fang mask, a Papua New Guinea shield, an Edwardian portrait, and a Boulle commode, all in the same vignette.) But La Biennale still felt oddly enervating. Attendance figures could have been much better, too; this year’s La Biennale attracted 32,878 visitors, a far cry from the 60,000 to 80,000 of a decade ago.

Call it Paris when it fizzles.

Once upon a time, La Biennale was likened to "falling down a hole into Wonderland" for its palatial displays, museum-quality wares, and imperial swagger. It was a sparkling, impossibly elegant biannual celebration that kicked off la rentrée, that culturally crucial moment when France’s summer holidays give way to a daily grind—i.e. real life, from school to pony clubs to yoga classes—that lasts until les vacances begin in July.

In recent years, though, La Biennale has become a bit tired. Hence a major reboot driven by Paris gallerist Mathias Ary Jan, who was elected last October to be the president of the Syndicat National des Antiquaires, a group of some 400 dealers that owns the fair. Ary Jan has coaxed American billionaire Kip Forbes (connoisseur of Second Empire art and objects, owner of Normandy’s Château de Balleroy) to become La Biennale’s new president and the head of its Biennale Committee. Forbes’s job, no easy task given that antiques are far from fashionable these days, is to mobilize new collectors to become La Biennale fans. He is joined in this effort by a committee that includes eight powerful and passionate aesthetes, among them Prince Amyn Aga Khan, AD100 decorator Jacques Garcia, filmmaker Jean-Louis Remilleux, and Gary Tinterow, director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

The SNA also reduced the number of participating dealers, 95 to last year’s 124, and regularized booth sizes and positioning, edits that are intended to emphasize egalité in a world that jealously guards its hierarchy. But the organization could do nothing about the mood at La Biennale. (The name illogically clings to the every-two-years appellation of old, though it is now an annual event, arguably to hold its own with the international competition.) It seemed hushed, a quality that made the event seem out of step in an age when TEFAF, Frieze, Masterpiece London, et al., have become electrifying destinations.

Part of the problem is that La Biennale is just one of many too-closely-scheduled fairs trying to pry open some of the same wallets. It also needs a strong identity, one that should position it as the undisputed queen of la rentrée and not just a duchess. Especially so during a breathless week that, in addition to masses of gallery events across the city, featured Parcours des Mondes (a salute to tribal art in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, with 60 participating dealers and multiple venues), major exhibition openings at the Petit Palais and Musée Marmottan Monet, a bracing interior design showcase organized by AD France, a splashy soirée at Sotheby’s, and the gargantuan Maison&Objet products exposition.

Mind you, the first annual edition of La Biennale was most emphatically not a flop, and, as always, I coveted more things than I could possibly afford. The press office trumpeted more than a dozen dealers’ post-show claims that sales had been "encouraging," one touting a visit from actress Eva Longoria. Top decorators were out in force, including Garcia, Jacques Grange, and Studio Peregalli’s partners Laura Sartori Rimini and Roberto Peregalli. That said, there was a fair amount of complaining, especially among les Gaulois. "Remember," one regular attendee told me, "the French always see the dark side."

Some visitors sniffed that the jewelry dealers, overrepresented in previous years but which have been pared back to a handful, were not popular household names. (One hears that the big guns, namely Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Boucheron, and Chaumet, may reappear in 2018, two years after a square footage–related contretemps with the SNA.) A recently installed independent vetting committee that SNA president Ary Jan calls “the most rigorous in the world” discovered at the last possible minute that Galerie Lumière’s chandeliers “did not meet the new international standards of excellence required for the Biennale.” Which explained the dark curtains that were hastily, haphazardly hung to conceal the offending lusters.

Traditionalists questioned why the gala dinner was held on Saturday, considering that the old guard, who season the opening party with ancient titles, don't leave their country houses on weekends. ("One never goes out on a Saturday night," I was informed.) Couture gowns were plentiful, though, and worn with fetching nonchalance, as if, one Frenchwoman explained, “We are just going out to the bakery.” An unexplained glitch left some diners, including a museum director and at least one committee member, without table assignments. (Full disclosure: I and a handful of other journalists attended the black-tie event, at which some 820 guests dined on Potel & Chabot’s [poteletchabot.com/en/home.html] menu of roasted sea bass and lime pavlova.) Some of the rich Americans normally seen swanning about the gala and the Sunday-morning VIP vernissage reportedly chose to bypass La Biennale’s opening weekend so they could party just a bit longer in Venice, where the 74th annual film festival and its related shindigs were winding down.

"This is the only opening that matters this week,” a local nabob cattily whispered in my ear at Galerie J. Kügel’s cocktail party in its luxurious quai Anatole-France premises, the day after La Biennale officially opened. It was seriously impressive. Dealers Nicolas and Alexis Kügel recently snapped up the next-door hôtel particulier to create exhibition rooms for old-master paintings and sculpture and wanted to trumpet the expansion. (If the antiques market has softened, the Kügel frères and their clients haven’t noticed.) The hours-long soirée was smart, effervescent, crowded, and posh, the grandest title belonging to Princess Maria Pia of Bourbon-Parma, daughter of Italy's last monarch. What the party lacked, though, was youth, the elusive fresh-faced audience that every fair and shop chase nowadays. "Everything here is antique," a decorator quipped as silvery trays of hors d’oeuvre floated past. "Even the guests."

Many of those sipping Kügels’ free-flowing Pol Roger had been stunned to read, on the morning of the gala, “Paris Biennale Out of Breath,” an unexpectedly harsh smack-down written by dependably testy Le Figaro journalist Béatrice de Rochebouët. The aristocrat declared that the fair was “struggling to be reborn,” dismissed its atmosphere as “sad,” and challenged the SNA’s improvements to “be more radical, less cosmetic.” Then, she added with a rapier thrust, “There are too few masterpieces in sight.” La Biennale supporters were shocked as well as resigned (“She hates everything,” one said), but several admitted that the show did feel rather quiet, despite the ancien-régime bling on tap at the boiseried booths of Steinitz, Röbbig München](http://robbig.artsolution.net/), and the like. “There is no reason to put on something so bourgeois,” a woman told me over cocktails at Kügel.

As for the Grand Palais, it won’t be La Biennale’s home for much longer, which creates another headache for Ary Jan and his crew. The immense venue, constructed for the Éxposition Universelle Internationale of 1900, closes again in 2020 for additional renovations, leaving the Biennale searching yet again for a new home. (From 1994 until 2006, during the Grand Palais’s previous bout of restoration, the fair was held at the Carrousel du Louvre’s exhibition hall, a vast subterranean space underneath the palace of the same name.) One solution? “I think we’ll have to construct a contemporary building, a building with distinction,” François Belfort, the SNA’s director general, was overheard saying at a press luncheon. It was a statement that seemed to put the cart before the horse, given La Biennale’s current aches and pains.

So, what is La Biennale Paris to do? I’ve a few suggestions.

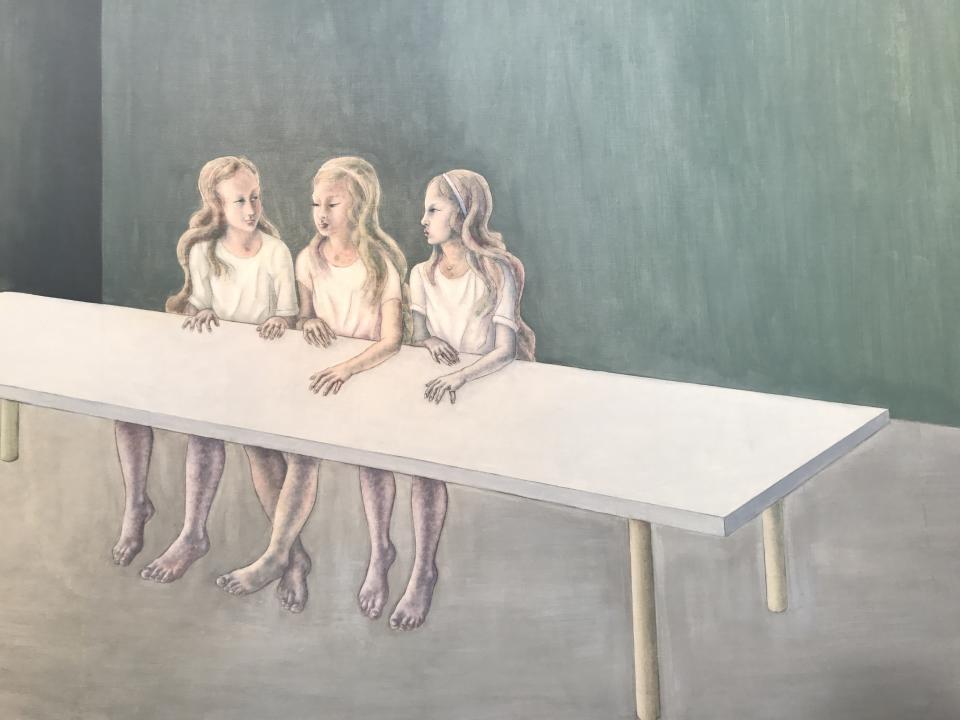

Ask white-hot French decorators like Vincent Darré, an inventive stylist such as Aurore Lameyre of AD France, or a fashion-world mastermind like Alexandre de Betak to advise on the appearance of the booths as well as overall show. Who can forget how fabulous Karl Lagerfeld made the Biennale look for its star-studded 50th-anniversary celebration just five years ago? And please deep-six stage designer Nathalie Crinière’s central bar area installation—its surrealistic mirrors-and-greenery scheme recycled from last year.

Bring into the fold more A-list international dealers, exquisite as well as edgy, to amp up the gravitas and to shake things up. Make the gala a fantastical moment—I’d call on Anne Vitchen, who conjures up meltingly lovely flower arrangements for the Ritz—and schedule it for an evening that makes social sense. (A bit of after-dinner dancing might help, too.) Add some jazzy antiques admirers to Forbes’s Biennale Committee, like artist George Condo, who owns a Pierre Migeon commode made for Madame de Pompadour. And why not invite Brigitte Macron, wife of the French president, to lead the honorary committee? In short, give La Biennale some juice.

The Best of La Biennale Paris