'Halt and Catch Fire' Should Have Failed. Instead, It's an Unlikely Success of the Peak TV Era.

"You've come on a funny day."

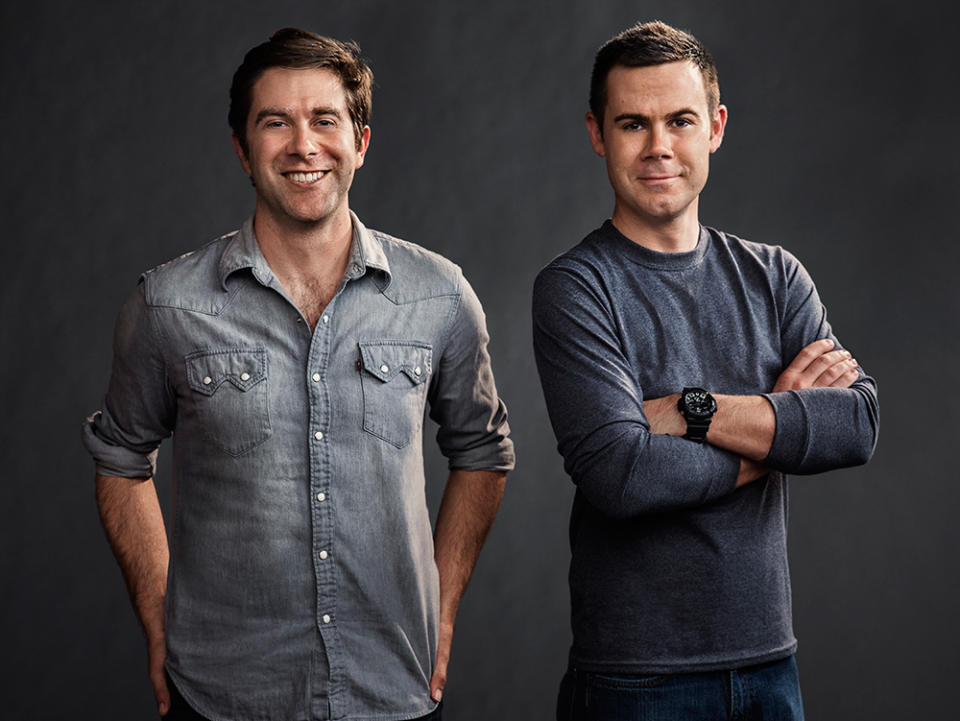

Chris Cantwell, the co-creator and, as of this season, co-showrunner of Halt and Catch Fire, sits in the director's chair between set-ups on the Atlanta soundstage where the series is shot. It's not a chair he's used to occupying: This is his first day ever directing the show.

"I spent months freaking the fuck out, for lack of a better word," he says. Clear-eyed and clean cut beneath a baseball cap, he's in his early 30s but looks every bit the rookie he worries he is. "But I've prepped as much as I can, and I've known the actors for so long, so it feels good."

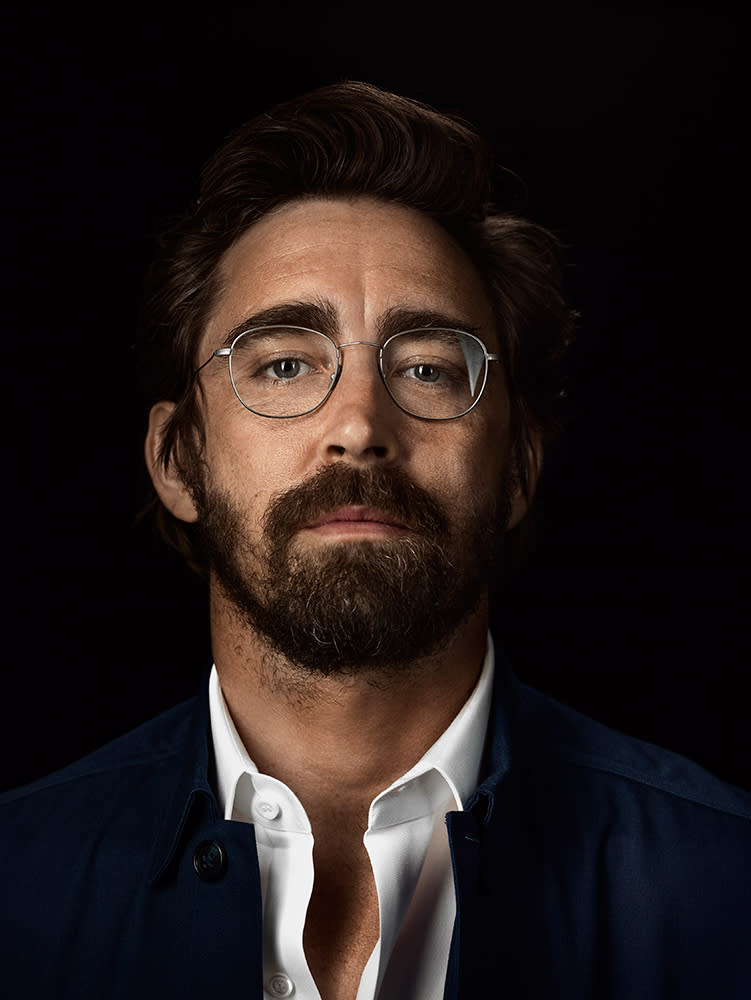

On deck today: a scene in the California home of programmer Gordon Clark (Scoot McNairy). After spending the first two seasons in the Dallas-area Silicon Prairie, Gordon and the rest of Halt's mercurial characters-his equally intelligent but business-savvier wife Donna (Kerry Bishé), her wunderkind punk partner Cameron (Mackenzie Davis), their genial Texan major domo John Bosworth (Toby Huss), and their strange, possibly sociopathic yuppie frienemy Joe McMillan (Lee Pace)-have packed up stakes and put down roots in Silicon Valley. Their move takes place in 1986, at a time when the money and power of tech had begun reshaping San Francisco, and the rest of the world, in a major way. Gordon's changed circumstances indicate that they've reshaped the lives of Halt's heroes as well.

Indeed, Halt seems to reboot itself with each new season. It began as a familiarly anti-heroic drama about Joe's hostile takeover of a tiny Texas electronics company in a quixotic quest to design a next-generation personal computer, but by Season Two the focus was on Cameron and Donna's joint venture Mutiny, a video game company turned early Internet service provider and proto-social network. From the new setting to the new showrunners (Jonathan Lisco, who was at the helm for the series' first two seasons, departed for TNT's Animal Kingdom), the leap from Season Two to Season Three is equally dramatic. "We almost err on the side of so much reinvention that it's frustrating," Cantwell says. "But the technology industry is like that. Having to keep up with that constant change allows us to reinvent characters, to do some really cool stuff."

The technology industry is like that. Having to keep up with that constant change allows us to reinvent characters, to do some really cool stuff.

It's also helped the show itself catch fire-critically, if not commercially. After early growing pains driven by antihero fatigue (not helped by AMC's decision to plop Joe and company right into the time slot recently vacated by the network's previous period piece Mad Men), the show slowly evolved into a story about its passionate core quartet of tech whizzes struggling to work together, rather than to tear each other apart. By the time the women took center stage in the second season, critics were fully on board, making Halt one of 2015's most acclaimed shows. Audiences, however, had yet to follow suit, and the series' low ratings made its renewal an iffy proposition for months before the network finally gave the go-ahead.

"What I was told was that the journalists were the one who championed this thing," McNairy confides during a break in shooting. "Like, 'Please come back, please come back, please come back.' I think the network was like, 'Well, they definitely liked the show.'"

So does the network itself. "The guys from New York talk about it like fans," Cantwell says. "Yes, they factor in all of the analytics and data in determining our future, but so far a big portion of [their decision-making process] has been, 'Do we like this show? Yes, we like it a lot. Just go do your thing.' Like the saga of the Internet upstarts it chronicles, Halt itself is, as cast and crew frequently call it, an underdog story-albeit one with an unusual amount of leeway to do things its own way.

Hence the series' latest reinvention, and its third chance to snag an audience commensurate with the show's quality: Halt and Catch Fire Season Three, which begins tonight. That fact alone makes Halt something of a success story-or what passes for one in the era of Peak TV, in which hundreds of scripted shows struggle for a share of the public's attention, an uphill battle for any series without dragons or zombies in its arsenal. Getting that third season is a rare case of a show being rewarded simply for being well made rather than pulling in ratings or tapping the Twitter-trend zeitgeist. It's a struggle that'd feel familiar to the characters themselves.

"There's an intrinsic metaphor to what we're doing here," Kerry Bishé tells me before shooting that afternoon. "We're making a TV show and the characters are making their technology, but the big goal is making a beautiful, perfect product that can go to market and succeed. It'd be nice if more people watched our show, but I'm doing work I love and value. We define ourselves so much by success in our jobs that I think it's worth investigating what success is. What counts. What matters."

We're making a TV show and the characters are making their technology, but the big goal is making a beautiful, perfect product that can go to market and succeed.

At first, "What matters?" was a question the show's creators themselves couldn't answer. When Cantwell and Chris Rogers wrote the pilot for Halt and Catch Fire, they had little in mind but jumping on board one of the shows they already liked. "We're both in our early 30s, so the shows that made us wanna do this were the great 'difficult men' shows: The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, The Wire," Rogers says. "We wrote the pilot in a way that was set up to ape them: Joe McMillan is a traditional antihero, and the world is organized around him in that way." But when the pilot was bought by AMC for production, rather than simply used as a staffing script to land "The Chrises" (as Halt's cast and crew universally call them) in a writers' room for a preexisting series, things changed. "As we got in there and started doing it, we had a writers' groove. We figured out what was our voice, as opposed to the voice that felt like it was emulating the shows we liked."

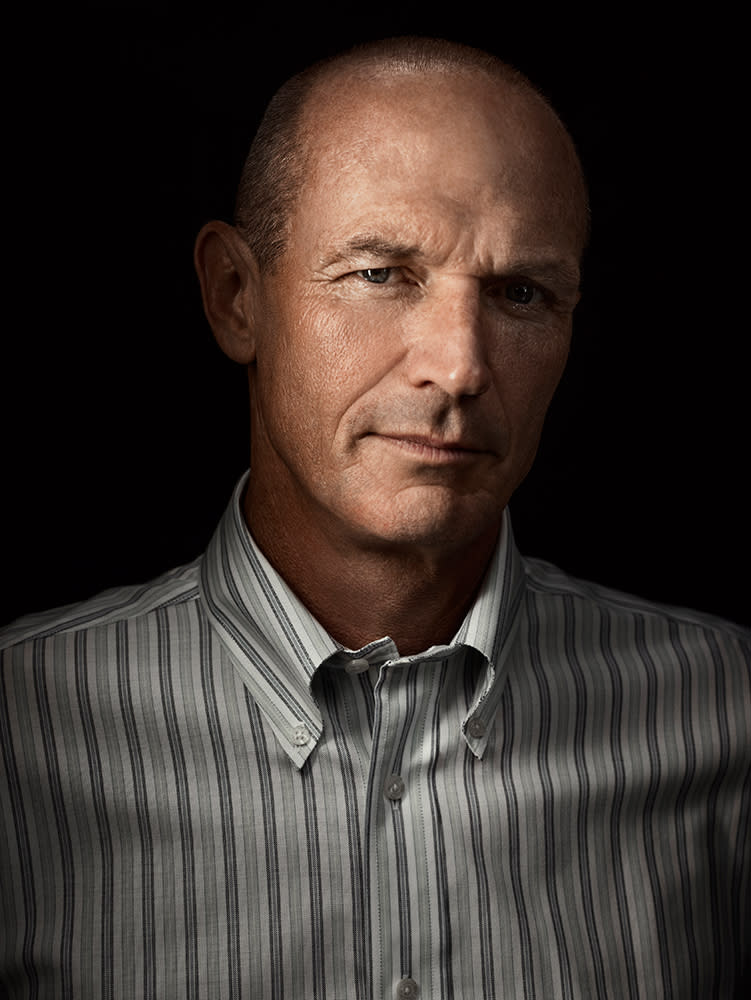

For a while there, it was rough going. While the pilot wowed many viewers with its impeccable period-accurate '80s soundtrack and design (to this day, it puts Stranger Things to shame), subsequent episodes felt like one protracted shouting match between the show's main characters, fueled by Joe McMillan's distinctly Don Draper-esque narcissism. The tall, dark, and handsome master of the universe; the harried brainiac husband; the overworked and underappreciated wife; the brash young rebel: Joe, Gordon, Donna, and Cameron were, for a while, little more than the sum of their parts. "For me, Season One wasn't the easiest thing in the world to watch," says Toby Huss, whose character John Bosworth was the man Joe duped into allowing him to take over the business. "It was hard to watch these jangly people beat on each other."

Season One wasn't the easiest thing in the world to watch. It was hard to watch these jangly people beat on each other.

One of the earliest signs that Halt had potential came from an unlikely source: Bosworth himself. At first, the old-school, back-slapping salesman was the younger characters' primary obstacle to making something new and exciting. On any other show, that's where he might have stayed: a conservative Texas shitkicker designed as an antagonist for the main players to surmount. "We had a similar image of John when we wrote the pilot," says Cantwell. "We didn't know how long he would last."

Then something happened: Huss, the veteran actor-comedian whose resume includes stints on material as disparate as Carnivale and Reno 911!. "Toby came in and did an audition that was 180 degrees from what we were thinking," Cantwell says. "We thought Bosworth would be this grounded, slow-talking Texan, and Toby is so wiry and full of energy that the casting director couldn't keep him in frame. We were like, 'This is insane.'" Once the character started doing scenes with the much younger Cameron-his cultural and temperamental opposite in many ways-the paradoxical chemistry between Huss and Davis was too much to ignore. "We saw him do scenes with Mackenzie and went, 'Oh my God, we gotta see more of that.,'" Cantwell continues. "Credit to Toby for making that such an option," says Rogers. "He showed up and did what he did, and we felt we'd be fools not to use other colors for him."

So Boz, as he's known to the show's small army of young coders, slowly jettisoned his old ways to become a key component of Cameron's upstart business. "Chris and I's rule of thumb was no matter what, we've gotta keep an open mind, because we're gonna be surrounded by people who are extremely talented and have done this longer than us," Cantwell says. "I feel like that's served us well, because that's what's given us John Bosworth."

"That's very kind of them," Huss says of his writers' praise, "but I see it as all the writing, you know? This guy really shouldn't exist. He's really an outlier. He realized that to open up to this new thing was the only way to learn and grow as a man. It was a vivisection, but it was necessary, and it's a great credit to the writers to make this arc for this guy."

Before long, similarly unpredictable role reversals and nuances became the norm. Cameron went from a perpetually angry middle finger in human form to a dedicated, ambitious visionary. Gordon came out of his middle-management shell, but his genius was tempered by slowly mounting mental difficulties brought on by exposure to toxic chemicals in the computers he engineered. Donna, perhaps the biggest revelation, went from supporting character to main player, the one character who best balanced the needs of creativity and commerce in the workplace. The role suits Kerry Bishé, who even in a cast that's clearly thought a whole lot about what they're doing stands out as something of a philosopher-king in conversation. "They laid in really heavily to a lot of stereotypes about TV moms, and it was nerve-wracking to put your trust in people like that," she says. "But it's turned out to be a wonderful trip: all of the steps along the way to waking up to your ambition, stepping into yourself, becoming a confident actor in the world."

Even Joe, the American psycho who is the Chrises' most admittedly derivative creation, became an engaging enigma rather than an off-putting one. His history of severe abuse and his AIDS-era paranoia about love (McMillan is bisexual) made him a kind of palimpsest, constantly rewriting himself to suit the needs of the moment. "I see someone who's trying to be someone he's not," says Pace, whose beatifically beautiful face gives McMillain the vibe of an ecstatic saint in a Renaissance fresco even when he's smashing the scenery. "The car, the sunglasses, his whole way of being-it's like a mask he's been wearing since he was a child, a persona he could maneuver with." By the time he shows up this season, with a fortune earned from anti-virus software he stole from Gordon backing him up and a new-age guru vibe swiped from Steve Jobs, his inscrutability has gone from infuriating to fascinating.

To hear both creators and cast tell it, much of this evolution is a direct result of the extraordinary lengths to which the actors have gone to dig into their roles. "We feel proprietary about this," says Huss. "This is our show."

That sense of ownership begins at Pace's home, where the cast gathers on their own time and own dime to discuss their material. "We get together and read the scripts on weekends, just to see what we might find, and we have a few bottles of wine and talk about it," says Pace. "We make dinner, we hang out for four or five hours, and we go through the script, just the actors-because we all like each other," Huss elaborates. "It's funny, the way they cast it, because we're all sort of weirdos, for lack of a better term. We all have a bit of an iconoclastic edge, I think. That's our nature. So all these disparate elements came together to make a thing we all really care about it."

"There was this sense of us being a scrappy little startup," says Mackenzie Davis, whose startup-founding character Cameron Howe is the scrappiest of all. "The Chrises weren't jaded industry vets when they started the show, and speaking exclusively for myself, it was my first big job. And the show has continued with this sort of small family feeling. The five of us move to Atlanta each year, shoot in an old dog-food factory for four months, and just work really hard, as a company, to make something we think is cool and beautiful. I don't know what the show would be like if we didn't work so collaboratively, and so far outside the normal working hours. It would be a totally different beast."

New to the family and to the weekly wine-fueled get-togethers this year is actor Matthew Lillard, the Scream and Scooby-Doo vet who convincingly inhabits Ken Diebold, a venture-capital robber baron who invests in Joe's latest venture. Along with Annabeth Gish as rival VC hard-charger Diane Gould and Manish Dayal as wide-eyed young coder Ryan Ray, he's one of several key additions to the cast, and his enthusiasm for the project is so overwhelming that he jokes the network should be notified as proof of his loyalty. "I found it incredibly refreshing to come on set and be with people that were only concerned about the work," Lillard says. "That's a hard thing to do on television. It's fast, you're doing lots of pages, you have long hours-you know, it's a grind. But it goes back to the actors, sitting around a table, drinking a glass of wine, talking about scenes, talking about relationships, talking about what happens. These guys are out there the day before, working on next week's scenes. Ratings be damned, what they're trying to do is great work."

It goes back to the actors, sitting around a table, drinking a glass of wine, talking about scenes, talking about relationships, talking about what happens. Ratings be damned, what they're trying to do is great work.

Consciously or not, Lillard's description echoes the cast's take on the characters they play. "Something I discovered at the beginning of this season is that none of these characters care about money," says McNairy, though he's incongruously ensconced on the set of a luxury hotel at the time. "They're so focused on innovation that they're so quick to just"-he snaps his fingers for emphasis-"give away their salaries, because the vision is so much more important. Their overall mission is to change the world."

"Don't think it doesn't bleed into us!" he continues, leaning forward in his chair. "Lee and me will get into it about something, and I'll be like, 'Lee, that's the character saying that, not you.' We have to be like, 'Stop, stop, everybody-this was what was written on the show. Let's not let our own personal feelings get involved.'"

"Mackenzie and Scoot and Kerry and Toby get so sick of hearing me defend Joe McMillan," Pace agrees with a laugh. Sure enough, he launches into a multi-minute revisionist-history version of the first season's climactic act of industrial espionage, recasting Joe as a scapegoat unfairly blamed for the mistakes of his colleagues.

This is the kind of conviction that can't help but show up on screen, making each side of any given argument over the direction of the group's joint ventures feel equally persuasive. This, ultimately, is Halt and Catch Fire's killer app. When Gordon and Cameron clash in Season One over whether her warm, advanced, Apple-esque user interface should be scrapped to make their computer lighter and cheaper, or when Cameron and Donna argue in Season Two over whether Mutiny should abandon its gaming focus in favor of chat rooms and community, or when new hires and attempts to close old wounds come up in Season Three, viewers genuinely don't know which is the correct side to take. Good, even great, dramas frequently telegraph who's right and wrong in any given dispute; Halt leaves it tantalizingly, gorgeously uncertain.

"I love that," says Davis unequivocally. "We talk about that all the time. Ego comes into these arguments, because of course each side is convinced that their vision is the right one, but still, it feels like the ego is balanced by the belief in something pure. There isn't a right and wrong to each disagreement. There are just constant forks in the road. You hope the fork you choose will lead you to become Steve Jobs, but most of them don't."

McNairy's take is more profane, but ties the story's shades of gray directly to the actors' investment in their roles: "Everybody's got their heads so far up their asses with their characters, which makes the audience watching it think, 'Both ways could work.'"

"The more invested everyone is in what they're doing, the more it impacts your experience," Lillard agrees. "When a show is trying to be great, that's more prominent. Does that make sense? If you're doing a show for the tenth year and you're just making your paycheck, doing 22 episodes of television, and you're burned out, nobody gives a shit."

"It's so funny," Huss laughs. "The show is about a bunch of outsiders who are trying to come together, however flawed they might be, but they're trying to put some of their flaws aside for the greater good. That's what this has all been about."

The show is about a bunch of outsiders who are trying to come together, however flawed they might be, but they're trying to put some of their flaws aside for the greater good. That's what this has all been about.

Touring the set for a final time, the characters' quirks are evident in the environment. Cameron's office has an edgy air, as if you could jam a desktop computer inside the Never Mind the Bollocks cover. Donna's is a projection of professional efficiency. Bosworth's looks like a room where you can exchange hard drinks and handshakes. Joe's apartment is immediately identifiable from its cold, '80s-modernist minimalism and planes of reflective glass, the better to show him the man he wants to be. And the living room and kitchen where Gordon's puttering around are populated by equal parts children's breakfast cereal and grown-up booze. Each feels recognizably human-and that, at least, is an element of the show that has remained constant from the start.

"It was important to us that this would be a story without guns," says Chris Rogers. "When you don't have someone dictating the action of the scene with a firearm or some kind of bodily threat, then you have to keep going back to the characters to figure out what's gonna happen next. I know it sounds kinda writerly, but I think it keeps you honest."

"Any time two people get together and eat a sandwich and they're in danger of being murdered by dragons or eaten by zombies…I dunno, that gets fucking exhausting to me," Huss echoes. "I dig it: People wanna go on a roller coaster and lose their shit. You might go to AMC to watch The Walking Dead, but hopefully you stay to investigate some show like ours." That's the gamble the network has taken, sneak-premiering Halt's third-season premiere right after the zombie spinoff Fear the Walking Dead this past Sunday.

Any time two people get together and eat a sandwich and they're in danger of being murdered by dragons or eaten by zombies...that gets fucking exhausting to me.

But in the Peak TV era, it doesn't necessarily need to do Walking Dead ratings, and its continued existence is living proof. "If it was ten years ago and it was on a network, or even HBO, it would have been yanked by now," Huss says bluntly. "That's the business question around Peak TV," Bishé elaborates. "By many different standards, we should have been cancelled a long time ago. [But] the sheer amount of television is making people reassess how to judge a successful show, what the benchmarks are, what they really want out of making TV. We're lucky that we've got a network that wants to keep giving us chances."

And if it never quite finds an audience, at a time when so many alternatives exist? "I've always liked being part of a small thing that feels exclusive to the people that care about it," Davis says. "There doesn't need to be millions of people weighing in and writing a million think pieces about it. It just matters to the people that it matters to."

"I wish more people saw our show," Bishé laments "It feels a little like we're in a vacuum or bubble, working away in the dark." But then, like seemingly everyone involved in the creation of this show does eventually, she takes on the idealist tone of the underdog tech geniuses whose story they tell. "If you continue to do work you believe in, it means something. Whether a million people watch it or ten people watch it, it means something."

You Might Also Like