If Haiti falls to the gangs, who could rise to power? The list includes some alarming names

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The prime minister is stranded abroad and under pressure to resign. At home, political and civil leaders are unable to reach consensus to build a new government. Armed gangs have taken over most of the capital and continue to gain ground. An armed international force that might help is stuck half a world away.

That is the situation on the ground in Haiti, which remains mired in such chaos and near-anarchy that the United States fears any semblance left of government may collapse at any moment.

It’s raising a disturbing question: In the middle of the violence and the vacuum of power, who is going to end up running the country?

One alarming prospect: The situation is ripe for Haitians — victimized by the growing wave of unending violence, killings, kidnappings and rapes since the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in 2021 — to welcome a ruthless authoritarian leader who promises to put an end to the bloodshed.

History is full of men who rose to power because panicked populations turned to anyone who could end the chaos. Haiti could soon find itself in a similar situation, said veteran diplomat and experienced Haiti hand Thomas Shannon, a former under secretary of state who spent nearly 35 years in the U.S. foreign service.

“If we’re not careful we’re going to have another brigand claiming to be the rightful leader of Haiti,” Shannon said. “It’s very distressing.”

The gangs, Shannon added, are the only ones “working with completely alienated and disaffected people to address the immediacy of their concerns in a way that neither the government nor the international community can.”

Said Haiti-born political scientist Robert Fatton: “The gangs might well emerge as the arbiter of Haiti’s immediate future.”

Events over the past few days have hastened the maneuvering for power — Prime Minister Ariel Henry remains in Puerto Rico, facing U.S. pressure to step down. A multinational force to be led by Kenya to help Haiti appears far from deploying.

There is no shortage of candidates in Haiti who covet leadership. Some can make a case to a degree of legitimacy — former politicians, respected members of civic society, previous government officials. And some are essentially warlords with violent histories who have amassed a large armed following and are already laying a claim to leadership.

Here’s a look at some of the key figures jostling for power.

▪ Guy Philippe, a former coup leader who led the paramilitary overthrow of President Jean Bertrand Aristide in 2004. Philippe, 56, recently finished serving a six-year prison sentence in the U.S. on drug trafficking-related charges and was deported to Haiti in November. Since his return, he has been calling for Prime Minister Henry’s ouster, joining forces with members of an armed government environmental agency that has emerged as a paramilitary group.

While rallying the public to follow his revolution, he has also sought support from gangs and established politicians. Earlier this year, Philippe, who also enjoys the tacit backing of some members of Haiti’s private sector, extended a hand to Jimmy Chérizier, the influential gang leader who declared last week that the gangs are now one and called on gang members to take down Henry’s government “by any means necessary.”

While pleading with gangs to stop killing people, Philippe, a former police chief of Delmas in the capital and the northern city of Cap-Haïtien, also told the armed groups to listen to Chérizier. This week, as Henry struggled to return to Haiti, Philippe made a grab for the presidency as head of the Réveil National political party and as part of an alliance with one of Haiti’s most well-known leftist leaders, Jean-Charles Moïse. The latter proposed a three-person presidential council that would include Philippe, a member of the judiciary and a representative of the religious community.

Philippe’s National Awakening party has proposed that he lead the council despite Haiti’s constitutional ban on convicted felons holding office, and even announced on Tuesday his pending installation in the National Palace as transitional president under the proposed council, which has issued a five-point plan for governance. The installation didn’t happen but all eyes remain on the convicted felon who has been gathering crowds.

Philippe walks with a politician’s swagger as he works crowds. His ability to rally them, coupled with the Robin Hood reputation he developed as he evaded capture by U.S. drug agents for nearly a dozen years, has only helped increase his popularity. Fluent in English and Spanish, he’s taken his opposition to any foreign intervention directly to the Kenyan people, releasing a video in English warning that “imperialism is trying to use African and Africans again to stop our movement to free our country.”

Philippe is among a group of Haitian police officers who were trained at the police academy in Ecuador. That has further helped his popularity despite his well-known reputation within the ranks for helping turn Haiti into a narco state by accepting bribes to protect drug smugglers who used the island to ship Colombian cocaine to the U.S.

In a video address that circulated on Thursday,Philippe saluted the population for their “peaceful revolution,” and called on them to remain mobilized and vigilant.

“We are advancing and we will get to where we promised,” he said. “It’s the only way we can find a Haiti that is more just, with more equality.”

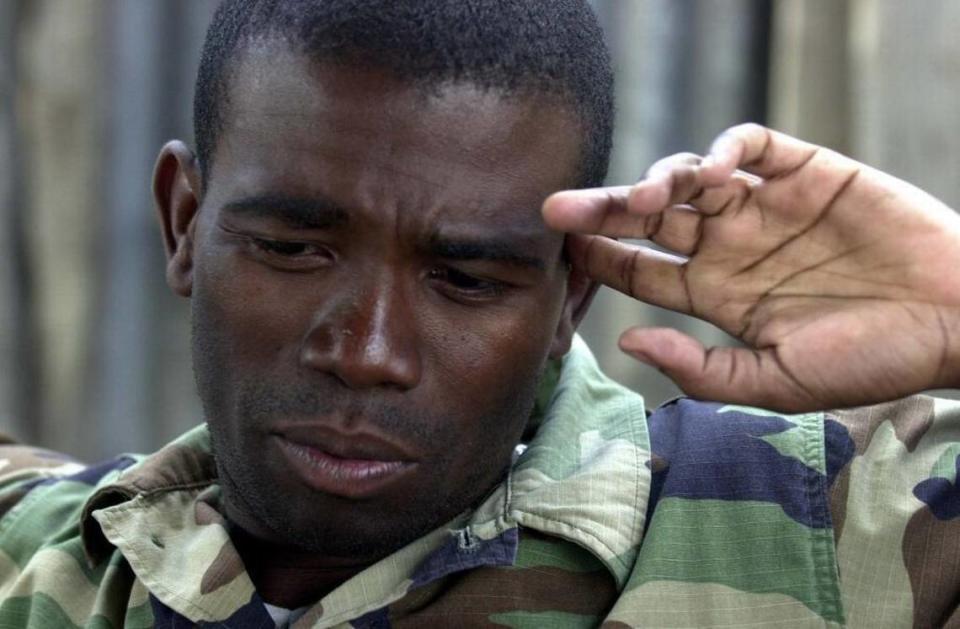

▪ Jimmy Chérizier, the leader of the G9 Family and Allies gang alliance goes by the nickname “Barbecue.” During press conferences he is armed and often dressed in camouflage gear and sporting a beret. Human-rights groups have linked him to a host of violent attacks and massacres, which he has denied. Chérizier, 47, has warned that if Henry doesn’t step down there will be “civil war that will lead to genocide.”

“Today, I am asking you, ‘Drop Ariel Henry,’ “ he said on Feb. 29 when he announced the gangs’ movement to take down the government. “Ariel Henry will fall.”

In 2021, Chérizier catapulted himself on the international stage by blocking the country’s main fuel terminal at the seaport, fanning a humanitarian crisis, and demanding Henry’s ouster. His second blockade a year later amid a deadly cholera outbreak led to Henry to request the world’s help to quell the violence by deploying an armed international force.

A former cop with the Haiti National Police, Chérizier spent 14 years in the force and was still on the payroll when he and two other members of President Jovenel Moïse’s government allegedly carried out a 2018 massacre in Port-au-Prince’s La Saline neighborhood. The incident was cited as among the reasons he was sanctioned by both the U.S. and the United Nations. Well-spoken and media savvy, Chérizier presents himself as a revolutionary fighting the elites and a system that has long victimized the poor and downtrodden.

Attempting to sound more like a statesman than a warlord, he turns his press events into a soapbox about Haiti’s problems, though he sometimes wears a bulletproof vest while speaking. “We are fighting for another society — another Haiti,” he often says. But according to a U.N. report, “Throughout 2018 and 2019, Cherizier led armed groups in coordinated, brutal attacks in Port-au-Prince neighborhoods.”

Chérizier’s critics say he makes his money through extortion and protection rackets that earn him and his gang top dollars. Since the U.N. in October approved the deployment of a Multinational Security Support mission to Haiti, Chérizier has publicly warned against foreign intervention and asked for amnesty for gang members.

He announced last week that all of the gangs have banded together under one umbrella, “Viv Ansanm,” Creole for Live Together.

“Haitian people, please, this is your battle,” he said, encouraging the public to support the movement and to refuse government efforts to stop it. “Today, the moment has arrived for us to do legitimate violence. Take to the streets with everything you have.”

▪ Jean-Charles Moïse, also known as Moïse Jean-Charles. An outspoken leftist leader who recently called on Haitians to “destroy the country” if Henry doesn’t leave power. Jean-Charles, 56, thrives on theatrics — he’s known for riding a horse during protest marches — and promotes his opposition to U.S. involvement in Haiti. His supporters fly the Russian flag as well as the red-and-black flag of the Duvalier dictatorship that ruled Haiti for decades.

He has warned foreign diplomats to stay out of Haiti’s internal affairs or risk being kicked out of the country.

Although Jean-Charles is a backer of the five-point plan, he recently came out in support of appeals court Judge Durin Duret Jr., one of the members of the proposed three-member presidential council.

Like other political figures, Jean-Charles, a former senator and presidential candidate, has his eye on the presidency. Any involvement in a transition would most likely make him ineligible to run if elections are set, and he is seen as more likely to seek to be the power behind the presidency.

In 2022, while transiting through Miami, the ex-lawmaker had his U.S. visa revoked and accused Washington of targeting him.

Jean-Charles has acknowledged the oddity of his alliance with Philippe, the man who led a bloody rebellion against his one-time mentor, Aristide.

▪ Durin Duret, Jr. A judge on Haiti’s Court of Appeals who was appointed in 2014 to lead the investigation into former President-for-life Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier when he made a surprise return to Haiti from exile in France.

In 2021, human-rights activists and lawyers accused Duret of denying justice in Haiti to victims of the brutal regime, noting that he had not submitted his reports on Duvalier’s crimes to the court of appeals. A former president of the National Association of Haitian Magistrates, Duret also sits on the Superior Council of the Judiciary, a judicial oversight body, as the representative for the Court of Appeals.

Duret’s name was first cited by Jean-Charles as the person who should take charge of the transition. The move has led some political observers to believe that he’s a proxy for Jean-Charles. Duret hasn’t made any public declarations about the presidency but a source told the Miami Herald he’s been working the phones in recent days, expressing interest and rallying support for the proposition.