Hackers hit University of Miami, posted patients’ private info. School won’t discuss details

Hackers targeted the University of Miami in a massive and brazen “ransomware” scheme that at the very least has compromised the personal information of an unknown number of medical patients.

The university is just one of a string of businesses, government agencies and schools hit in recent months through Accellion file-sharing software. They include the oil and gas giant Shell, law firm Jones Day (whose clients include former President Donald Trump), the supermarket chain Kroger and the Washington State Auditor’s Office, where it impacted more than 1.6 million people.

The scope of the data breach at UM isn’t clear. The university disclosed the attack in a web posting Tuesday — weeks after several other universities — but refused to provide details. The post downplayed impact: “Accellion had been used by a small number of individuals at UM to transfer files too large for email. The University has since discontinued use of Accellion file transfer services.”

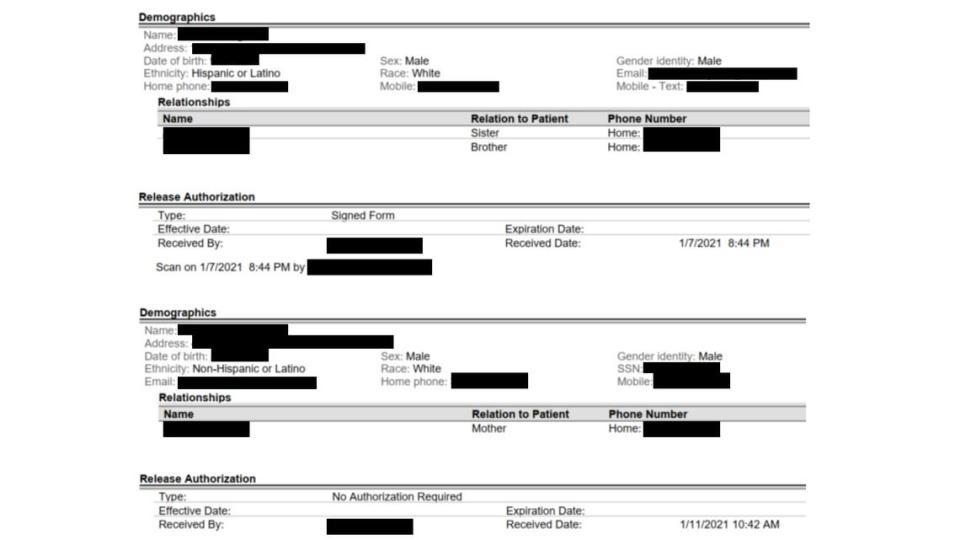

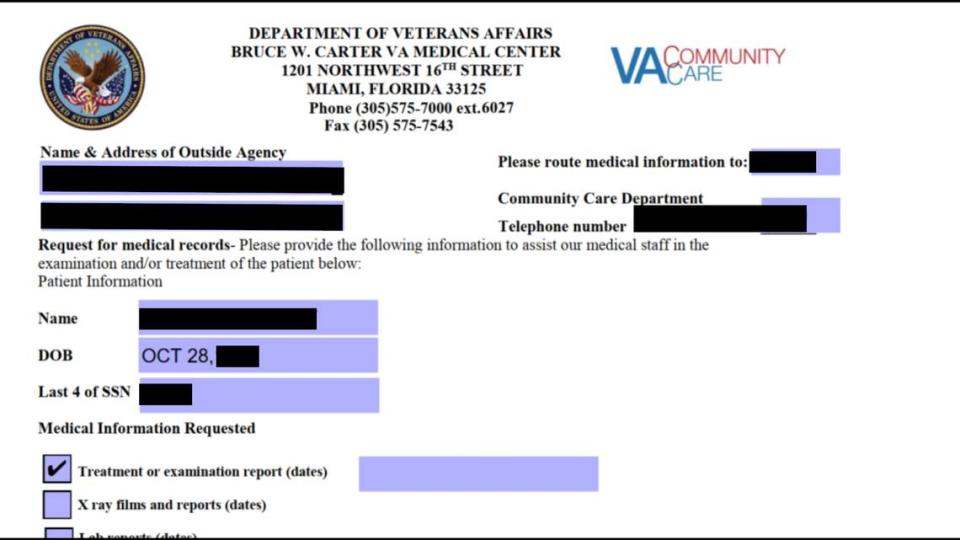

But cyber criminals posted a few dozen patients’ personal information, including their Social Security numbers and physical addresses in some cases, on the internet in the so-called “dark web” often used by digital crooks. Brett Callow, a cybersecurity expert based in Canada, said that amounts to an extortion threat — pay up or we’ll expose more of your protected data.

“It’s the equivalent of a kidnapper sending a pinky finger,” he said.

As of Wednesday, UM had not yet alerted affected patients but said it intended to do so. “Once our investigation and data analysis are complete, we will notify affected individuals under applicable laws,” the university said in the Tuesday posting.

UM didn’t issue a press release about the breach. Instead, it published an email message on a web page it uses for “key institutional emails that are sent out to various UM constituencies.” It was unclear who received the Tuesday email message about the cyberattack. At least two UM employees confirmed to the Herald they got the correspondence, but none of the three patients interviewed reported getting it.

William Budd, who has been a patient at UHealth since 1999 and is fighting cancer, said the first time he heard his information had been compromised was when a Herald reporter called him Wednesday. Hackers posted his email address and phone number online, but could potentially have more of his personal details and release them in the future.

“Let me sit down,” he told the reporter on the phone. “I feel like I should be sitting down to hear what you have to say.”

Budd said he hadn’t received any emails, phone calls, text messages or letters warning him that hackers had stolen his data. He said that if he had, he would’ve notified credit bureaus about it and taken other precautions weeks or even months earlier.

“What bothers me most is nobody from UHealth has contacted me,” he said. “That’s serious. It’s disturbing.”

Lisa Worley, a spokeswoman for UHealth, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

What we know about how UM handled the hack

The cyberattack was targeted through software produced by Accellion. The California-based company said in a Feb. 1 statement it “promptly notified” all of its customers about the “sophisticated cyberattack” on Dec. 23.

A university spokeswoman would not say when the school discovered the attack. It is unclear why UM waited until this week to disclose the breach. The University of Colorado, which got student grades and copies of checks stolen, put out information about the incident on Feb. 12. The Southern Illinois University School of Medicine divulged it March 4.

UM’s web posting said that based on its ongoing investigation, “the incident was limited to the Accellion server used for secure file transfers and did not compromise other University of Miami systems or affect outside systems linked to the University of Miami’s network.”

The university did not provide information on how many UHealth patients’ data may have been compromised or whether other university departments or students records were impacted. It is unclear whether UM received a ransom message or if it paid or was planning to pay the hackers.

Responding to questions, Megan Ondrizek, the executive director of communications and public relations at UM, emailed a short written statement that included some of the text in the Tuesday web posting and read in part:

“As soon as we became aware of the incident, we took immediate action to investigate and contain it. We also retained leading cybersecurity experts to assist with our investigation. We have reported the incident to law enforcement and are cooperating with their investigation.”

What was the massive cyberattack to Accellion like?

Accellion, a global cloud provider in Silicon Valley, suffered the hacking attack late last year that bled into the start of 2021. In some ways, the public and private entities affected are still dealing with the fallout.

It wasn’t a “conventional” attack, said Callow, who works as a threat analyst for Emsisoft, a cybersecurity firm.

Usually, hackers get access to information and lock it down or encrypt it. Then they ask for money to give it back, he said. In this case, the attackers stole sensitive information through Accellion to blackmail the organizations.

That put victims between a rock and a hard place: They either pay, trusting that cyber crooks will destroy data as promised, or let the data get online. Callow said there’s “ample evidence” they retain stolen data and then come back to ask for more money.

The method used wasn’t the only reason that made the attack unusual. The number of parties affected contributed too.

“I can’t think of any previous incident at this scale,” Callow said.

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, a federal U.S. agency under the Department of Homeland Security, issued an alert about the attack on Feb. 24 jointly with authorities in New Zealand, Australia, Singapore and the United Kingdom.

“Worldwide, actors have exploited the vulnerabilities to attack multiple federal and state, local, tribal, and territorial government organizations as well as private industry organizations including those in the medical, legal, telecommunications, finance, and energy sectors,” the statement read.

“In some instances observed, the attacker has subsequently extorted money from victim organizations to prevent public release of information exfiltrated from the Accellion appliance.”

Who are the cyber criminals behind the UM hack?

To investigate the cyberattack, Accellion hired FireEye Mandiant, a leading cybersecurity forensics firm, which shared the final findings in an 11-page report on March 1.

However, “it isn’t entirely clear who is responsible for the attacks,” Callow, the cybersecurity expert, said.

The researchers didn’t identify any hackers by name, but said they used a dark website known as “CL0P^_- LEAKS” .onion to release the stolen data.

Not much is known about the Clop ransomware gang, other than that they are probably based somewhere in Eastern Europe because they use the Russian language, Callow said. In this Accellion case, an outside group of hackers could have stolen the data and then provided it to Clop.

“That could’ve been the work of a third party, and they simply brought Clop on board because Clop has the expertise and infrastructure to run extortion campaigns,” Callow said.