Grumet: Many Texans must work for food stamps. But no work required for $92,000 payout.

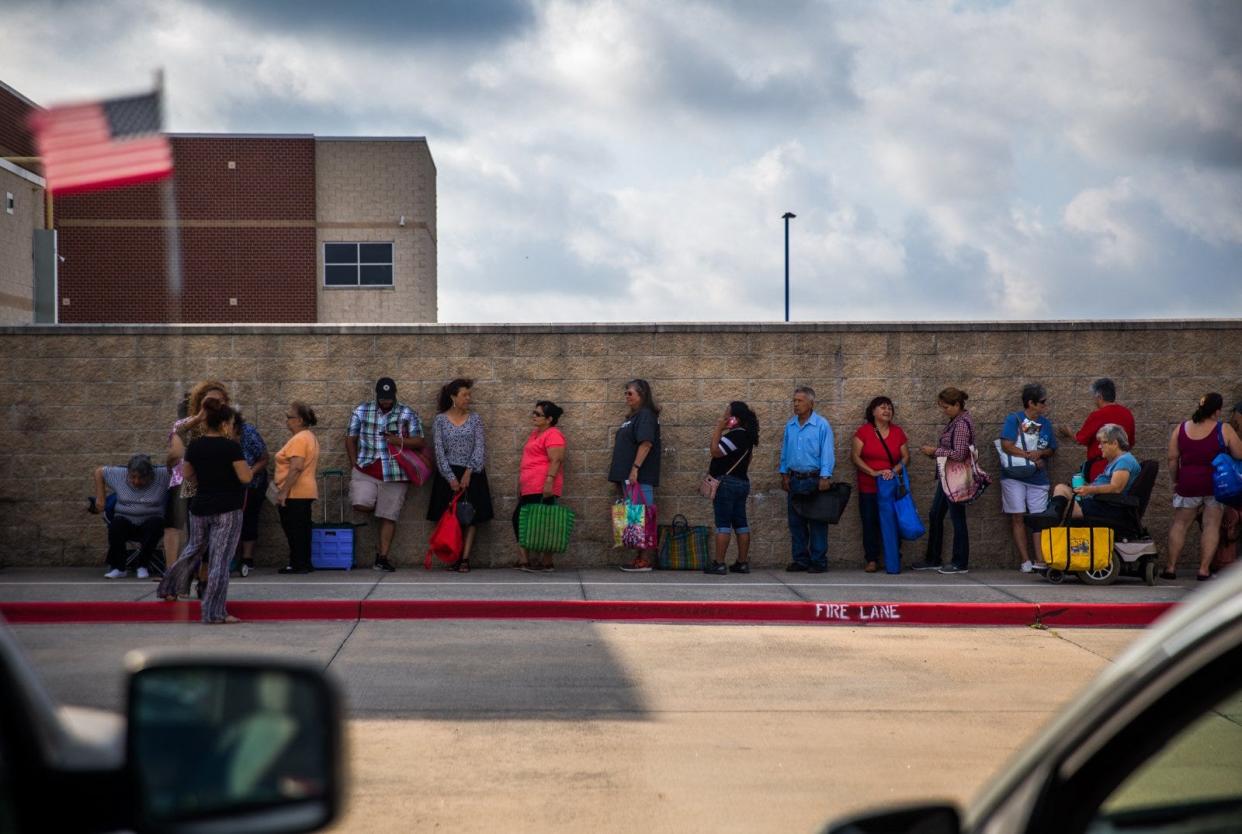

If you’re on food stamps, you can be sure the state of Texas will check up on you. Every six months, in fact.

You have to fill out new forms proving that you’re still poor and working at least 30 hours a week (unless you’re over 60 or physically unable to work). You have to demonstrate that your car isn’t worth too much, and, in some cases, show your housing and health care costs.

Every six months.

Just to get help to buy food — up to $939 a month for a family of four.

I kept thinking about that as I read a stunning story last week about government spending on the other end of the spectrum. As my colleague Tony Plohetski reported, Victor Vandergriff resigned from his post as a Texas Department of Transportation commissioner in 2018 — but the state continued to pay him for five years, in payments totaling nearly $92,000.

No one was checking up on Vandergriff. He didn’t have to justify himself every six months. The paychecks kept flowing, even though he stopped doing a job that, in fairness, he had quit.

When it comes to social safety net programs, our state is so worried that people might get something they don’t deserve. Where is that concern when it comes to someone drawing a state paycheck they didn’t earn?

The focus has been on the “holdover” provision in state law that allowed this to happen. To ensure the government keeps operating, original language in the 1876 Texas Constitution says that state officials remain state officials until they are replaced by someone else. So even though Vandergriff resigned, he remained a transportation commissioner on paper — and on the payroll — until Gov. Greg Abbott named a replacement this March.

In such a system, the onus is on the governor’s office to ensure that appointees who resign are replaced in a timely way. Abbott’s office didn’t respond to follow-up questions about why it took five years to name Vandergriff’s successor.

It's worth noting that the governor's office handles more than 1,500 appointments to various boards and commissions during each four-year term, and finding people with the right expertise and willingness to serve in these roles can take time.

Still, it's striking to see that Texas' systems are designed to provide grace periods and continued resources to those in power, while imposing rigid deadlines and an obstacle course of justifications for Texans in need.

The car conundrum

Consider the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, more commonly known as food stamps.

Most food stamp recipients must prove they’re working. Getting to and from a job often requires a car. To get food stamps, though, your car can’t be worth more than $15,000 — a value that hasn’t been updated since 2001 to reflect inflation.

Heaven help you if you’re a two-car household: The second car can’t be worth more than $4,650, a value set in 1973.

“The wrinkle is, through the pandemic, when used car prices accelerated, it meant people's existing vehicles became worth more,” Rachel Cooper, director of Health & Food Justice for Every Texan, told me. “So it also made it harder for (people) to qualify for SNAP.”

And some people actually lost their food stamps in the past couple of years because their used cars grew too much in value, she added.

Last month, the House passed a common-sense bill — House Bill 1287 — to provide a one-time adjustment to the allowable car value for food stamp recipients, and to create a process for considering future adjustments. The measure could be heard by the Senate Finance Committee this week.

Technically, it’s legislation about car values and benefits calculations. But really it’s about whether some Texans on the margins can qualify for the food their families need.

Difficult by design

Food stamps are just one example.

Consider Medicaid: Prior to the pandemic, some of the poorest kids in Texas routinely lost their health care coverage because the state used a flawed system to conduct random spot-checks for eligibility. New moms on Medicaid — nearly half of the women giving birth in Texas — lost their health coverage just two months after the baby arrived.

Federal COVID-era policies provided temporary relief, preventing anyone from losing health coverage during the pandemic. Lawmakers last session shifted Medicaid eligibility checks for kids to once every six months, and lawmakers this session are considering HB 12 to keep uninsured women on Medicaid for 12 months after they’ve given birth.

Meanwhile, as the pandemic-era protections lift, 2.7 million Texas women and children must once again prove to the state that they deserve health care coverage.

Applying for government assistance is notoriously tough. Nonprofits often have staffers dedicated to helping Texans navigate the bureaucratic maze, Cooper said.

The process is difficult by design.

“If you have a mentality that folks who need these programs are taking from everybody else, or somehow they're not working, somehow they're lazy, and now they're abusing the system, then then you build a system to lock people out, to make it so that it's only the desperate or the very well-resourced who make it through the gauntlet to get services,” Cooper said.

Contrast that with the ease with which Victor Vandergriff collected $92,000 from the state without doing a thing.

Vandergriff's case might reflect one extreme example, but it still provides an instructive view. Our state systems are designed to maintain Texas government, to keep officials and their compensation in place.

Imagine if our systems were equally focused on maintaining Texans themselves, ensuring the most vulnerable can get the essentials they need.

Grumet is the Statesman’s Metro columnist. Her column, ATX in Context, contains her opinions. Share yours via email at bgrumet@statesman.com or via Twitter at @bgrumet. Find her previous work at statesman.com/news/columns.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Work required for food stamps in Texas, but not for $92,000 payout