He grew up in West Africa. He never heard of MS-13. Then he fled to the U.S. — and ICE accused him of being a gang member.

The first time Youmbi Roberto Nfor heard of MS-13, it was from Donald Trump.

A native of the remote Grassfields region of Cameroon, Nfor spent the majority of his life more than 8,000 miles from Los Angeles, the birthplace of Trump’s favorite bogeyman, La Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, the notoriously violent street gang whose international presence is largely confined to the Northern Triangle countries of Central America (Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador) as well as Canada and a few cities in the United States.

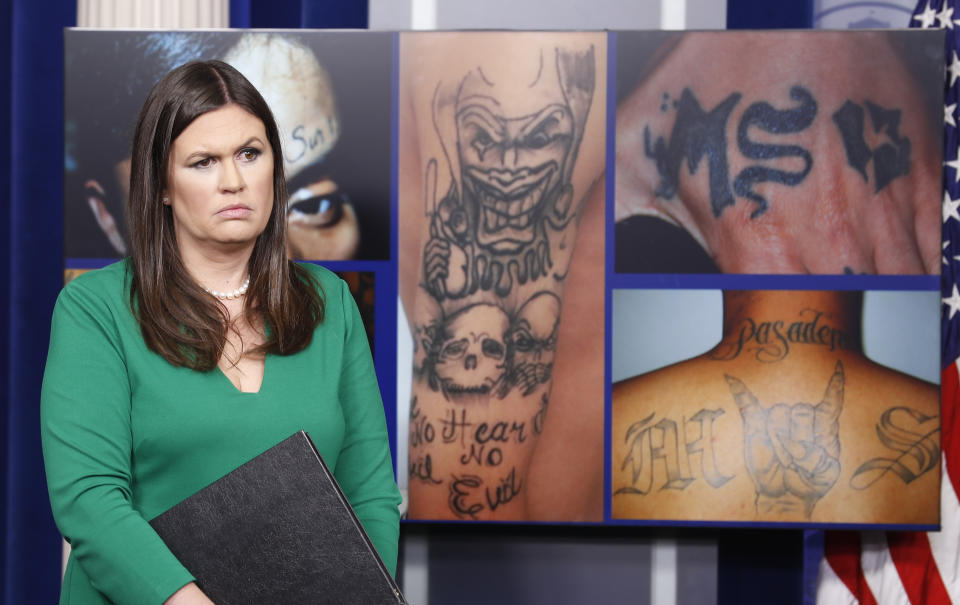

However, none of that seemed to matter last year when, in a bid to prevent Nfor from obtaining asylum in the United States, attorneys with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement accused him of being an MS-13 member. Their evidence was that Nfor, who’d been a tattoo artist in Cameroon, has several tattoos on his legs and chest.

An expert on gang symbology says his tattoos have nothing to do with MS-13.

Far from an isolated incident, the charges made against Nfor provide an extreme example of what many immigration attorneys say is a significant increase in the number of gang allegations raised against immigrants in all types of proceedings, from bond hearings to asylum requests to applications for green cards or citizenship. This trend, attorneys believe, reflects the influence of President Trump’s rhetoric on immigration enforcement and on MS-13 in particular, a frequent subject of speeches and tweets in which he has described the violent gang’s members as “animals” and an “infestation” in American communities.

It also shows how the immigration court system, with loose evidentiary standards, limited access to legal representation and overall lack of transparency, can be used by officials to keep out immigrants by arbitrarily designating them as a “gang member” or “gang associate.”

In 2016, Nfor, then 22, was forced to flee his home in West Africa under threats of death after he was caught having sex with a man. Not only is homosexuality a crime in Cameroon, punishable by up to five years in prison, but LGBT citizens are often subject to vigilante violence, including murder. With the help of a friend, Nfor was able to get a plane ticket from Nigeria to Ecuador, where he embarked on a grueling and dangerous journey to the United States, where he planned to request asylum.

After traveling by land for about a month and a half, Nfor said he finally reached the border between Tijuana and San Diego only to be turned away at the Otay Mesa port of entry. He ultimately entered the United States through the San Ysidro port of entry in early June 2016 and landed in immigration detention — for the next two years.

Though the way Nfor sought asylum is often referred to by Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen and others as “the right way,” immigrants who present themselves at an official port of entry and express a fear of returning to their home country are still sent directly to immigration detention, where they must wait to receive a “credible fear interview,” the first step in the asylum process. If they pass, they can request to be released from detention on parole or bond while they await a hearing before an immigration judge — which can take years. As of 2016, the year Nfor began his asylum process, the national average grant rate for parole requests from immigration detention was 5.6 percent. At the Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Ga., where Nfor spent the majority of his time in custody, the average grant rate for parole requests was zero.

Despite passing his credible fear interview, Nfor’s requests for release — which he drafted himself because, like the majority of people in immigration detention, he had no lawyer — were repeatedly denied.

During the course of Nfor’s detention at Stewart, one of the country’s largest privately run immigrant prisons, Donald Trump was nominated for president, won the 2016 election and took office.

Nfor recalls watching constant coverage of Trump’s campaign on CNN and describes how he and the other detainees “were scared that we are all going to be deported.”

It was during one of Trump’s televised speeches that Nfor says he first became aware of MS-13’s existence. Still, his knowledge of the gang never extended much beyond the fact that most of its members spoke Spanish, a language he barely understood.

In July 2018, more than two years after he first entered the U.S. in search of asylum, freedom finally felt imminent. An immigration judge granted his request for asylum, but instead of being released, Nfor was taken back to the Stewart detention facility in Lumpkin.

That day, Nfor recalls, two unusual things occurred. First, an officer at the detention center took pictures of his tattoos.

“That was the first time they ever did that,” Nfor told Yahoo News, noting that while he believes the officers who first detained him in California were aware that he had tattoos, no one had asked to photograph them before. Even as pictures were being taken, the interest in his tattoos was not clear. “They didn’t really ask what they meant,” he said.

At Stewart, like other large, privately owned prisons that contract with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, detainees are required to wear jumpsuits whose color signifies their status: red for those with a criminal record, blue for those whose only infraction was immigration-related.

For the duration of his asylum proceedings, Nfor had been in the second category. But when he was sent back to Stewart he was handed a red jumpsuit and directed to the section of the facility reserved for high-security detainees. Convinced this must be some kind of mistake, Nfor sought answers from a friendly guard who showed him a form and asked, “Are you … MS-13?”

Nfor was stunned. “In a way, it was funny,” he said. But his next thought was, “Are these people really trying to get rid of me? Do they hate me personally?”

For the entire time he’d been in the U.S., he’d been in custody, and every request for release on parole or bond had been denied or ignored. With this gang allegation, Nfor wondered if the U.S. officials were simply trying to make him so frustrated that he would give up and accept deportation. He’d seen it happen to others at Stewart, worn down by the miserable conditions compounded by seemingly insurmountable hurdles to asylum or other forms of relief. “Just, like, two to three weeks before I left the detention, a guy killed himself because he was facing deportation,” Nfor recalled.

Nfor said the guard who informed him of his alleged gang membership asked to see his tattoos, but when Nfor removed his clothes, the guard told him “there’s nothing that symbolizes MS-13.” Nevertheless, he was told he had to put on the red jumpsuit.

“How can I do that? I am not a gang member,” he protested. But the guard told him that Immigration and Customs Enforcement had the power to make that decision. “ICE is the one that has classified me like that.”

On July 30, 2018, attorneys with the ICE Office of Chief Counsel submitted a motion to reconsider the immigration judge’s July 18 decision to grant Nfor’s request for asylum, arguing that his “membership and/or affiliation with the MS-13 street gang” made him not only ineligible for such relief but provided reasonable grounds for Nfor to be considered “a danger to the United States.”

This was the first official allegation of gang membership against Nfor, and to back it up, the ICE attorneys submitted a written declaration from a deportation officer at the Stewart Detention Center who, unlike the guard who examined Nfor’s tattoos upon his return, claimed to find MS-13 symbolism all over his body. The officer even purported to detect signs of Nfor’s alleged gang membership from his hair, writing that upon his initial intake into ICE custody, Nfor “displayed three lighter colored braids which appear to form the letter “M” directly over his left eye.” It’s unclear what happened to the pictures Nfor said were taken the day he was transferred back to detention, but they were not included in ICE’s motion to reconsider, which relied solely on the deportation officer’s description of Nfor’s tattoos.

Nfor, who was able to rattle off the names of specific deportation officers he dealt with at Stewart, said he never met the officer who authored the analysis of his tattoos. “Where did she come from?” he wondered.

By the time he was accused of being a part of MS-13, Nfor’s case had been taken on by Martin High, a lawyer from South Carolina and volunteer with the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Southeast Immigrant Freedom Initiative (SIFI), which provides pro bono legal representation to detained immigrants at the five largest immigration detention facilities in the south, including Stewart.

To High, the notion that this young, soft-spoken tattoo artist from West Africa, who understood only a handful of Spanish words, could be part of a notoriously violent Latino street gang was “ludicrous.” The allegation, he said, amounted to ICE “just throwing mud at the wall.”

“Basically what they were trying to do was scare the immigration judge out of possibly releasing someone from MS-13, [which] in the current political climate would of course be problematic,” said High.

With a limited window to respond, High scrambled to locate experts who could help disprove ICE’s claim. He came across the LinkedIn profile of Darell Dones, a retired FBI special agent with expertise in decoding criminal insignia.

It just so happened that Dones, who now works as a consultant, had his own personal connection to the Southern Poverty Law Center — decades earlier, at the start of his FBI career, Dones had been stationed in Mobile, Ala., and his supervisor assigned him to protection detail for SPLC founder Morris Dees, who was being targeted by the KKK. Since then, he said, he’s been a member of the SPLC. “I believe in their cause; they do a lot of good work.”

When High told Dones he was representing Nfor’s case pro bono for the SPLC, “I immediately jumped on it,” Dones said, agreeing to waive his typically high consulting fee. Still, he says he made clear to High that he would be impartial, basing his analysis on his expertise and the facts available.

“I’m not a political investigator,” Dones said at the outset of an interview with Yahoo News. “I don’t really care one way or another what the political ramifications are. I’m just for right.”

After reviewing the documents in the case, Dones interviewed Nfor by telephone, questioning him closely about the context and significance of his tattoos and any interactions he may have had with gang members during his journey to the U.S., including potential offers for protection in exchange for sexual favors.

Nfor firmly denied having any such encounters, insisting, as he would later do in an interview with Yahoo News, that he had been completely unfamiliar with MS-13 until he heard Trump speak about it.

In a detailed affidavit submitted to the court, Dones not only disputed the existence of any MS-13 symbolism in Nfor’s tattoos — a crown, a Cameroonian symbol of determination and power; a clock, meaning “no time to waste;” and several miscellaneous music symbols — he highlighted the prominence of the color red in most of Nfor’s body art. Nfor said he used the color not because of any personal meaning but simply because it’s what was available. Members of MS-13, whose color is blue, are forbidden from wearing clothes or getting tattoos with the color red and, Dones wrote, “MS-13 Gangs have been known to severely assault, even kill” outsiders who display that color.

Based on the amount of red displayed in his tattoos, Dones assessed that if Nfor had, in fact, had any association with MS-13, he would’ve likely been “severely beaten and maimed, with his original tattoos brutally removed.” He added that homosexuality is also “severely frowned upon” among MS-13’s members and that, while there have been some exceptions, generally “Latino gangs do not recruit members out of their culture and race.”

Dones told Yahoo News that he couldn’t speculate on the qualifications or expertise of the deportation officer who submitted the declaration about Nfor’s tattoos or why the attorneys chose not to submit photographs or any other evidence to help make their case.

“It was kind of odd,” he said. “But my job was just to debunk what they presented, which was really nothing. They basically made my job easy. None of those tattoos were MS-13 tattoos.”

High also enlisted the expertise of Charlotte Walker-Said, an assistant professor in Africana Studies at John Jay College of Criminal Justice with a PhD in African History from Yale and specialized knowledge of Cameroonian politics, culture and society.

In addition to pointing out that MS-13 has no known presence in West Africa, Walker-Said explained that, as part of the Wimbum people — a “very small and insular community” from Cameroon’s remote and isolated Grassfields region — it would have been nearly impossible for Nfor to have had contact with anyone in El Salvador, Honduras or Guatemala, “as I have never heard of a Cameroonian from the Grassfields region immigrating to Central America.”

Walker-Said has been lending her expertise to immigration cases involving Cameroonian asylum seekers for about nine years, but she told Yahoo News that she’s recently observed a “dramatic shift” in the way such cases are handled, pointing to an increased emphasis on “credibility.” This likely reflects various policy and procedural changes implemented under the guidance of former Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who often claimed that the U.S. asylum system was overrun by fraud. Immigration advocates dispute this.

“Now you have an extremely hostile environment [where], basically, everyone is a liar until proven credible,” she said. “They’ll find any reason to cast doubt on the person’s credibility, allegiances, personal character. They are literally accusing people from West Africa with tribal tattoos of being part of MS-13.” She called the accusations made in Nfor’s case “utterly astonishing.”

On Sept. 13, 2018, the immigration judge officially denied the government’s motion to reconsider, finding that ICE’s previously unreported evidence of Nfor’s supposed gang membership was unconvincing in the face of the expert testimony disputing it. More than two years after he first crossed the border, Nfor was finally released into the United States. He’s now living in Plymouth, Minn., with an old friend from Cameroon, eagerly awaiting approval of a work permit.

Reflecting on all the obstacles he has had to overcome to get to this point, Nfor says, “I think it was worth it, definitely. At least I can be in peace and I can live without being afraid.”

High, Nfor’s lawyer, notes that the government had a 30-day window to appeal the judge’s final ruling if they did, in fact, believe he was a violent gang member, yet the deadline for that came and went without a word. “That kind of tells you something,” said High.

Peter Isbister, a lead attorney with the SPLC’s Southeast Immigrant Freedom Initiative, said he believes that the significance of Nfor’s case is twofold: First, “I think it really demonstrates how important it is for people to have counsel,” he said. While programs like SIFI and others have recently been expanding their pool of volunteer attorneys to provide pro bono counsel to more detained immigrations, Isbister emphasized that the vast majority of those who end up in immigration proceedings are forced to navigate the complicated system without a lawyer.

Isbister said Nfor’s case is also “very illustrative of the administration’s criminalization and demonization of the immigrant population in general. This particular case shows that the government is capable of doing that really to absurd levels.”

Fortunately for Nfor, with the help of a committed lawyer and knowledgeable experts, the accusations against him were relatively easy to dispel. But more commonly, such charges are being made against people from countries or communities where gangs like MS-13 actually exist, who have likely had some kind of encounter with their members, been witness to their crimes or have even been victims of their violence.

“Once the government tosses around gang allegations, they stick, and they’re hard to get rid of,” said Kate Melloy Goettel, an attorney with the National Immigrant Justice Center’s federal litigation unit.

Goettel, who previously spent seven years at the Justice Department’s Office of Immigration Litigation, is one of the attorneys involved in a federal lawsuit on behalf of a Salvadoran woman and her 4-year-old son who were separated by U.S. border officials in March 2018 after entering the U.S. to seek asylum.

The woman, referred to in the case as Ms. Q, was among more than 2,000 parents, including many asylum-seekers, separated from their children under the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance policy at the southwest border. However, months after the court-ordered deadline for the government to reunify parents with children under age 5, Ms. Q remained inside an ICE detention center in Laredo, Texas, 1,400 miles from her son, who was being held at a government shelter for unaccompanied immigrant children in Chicago.

The government had apparently deemed Ms. Q “ineligible” for reunification based on an arrest warrant from El Salvador that, they said, proved she had a criminal history — an allegation she only became aware of once attorneys with the Chicago-based NIJC began working on her case. Nearly two weeks after the reunification deadline came and went, the Department of Homeland Security finally produced the arrest warrant in question under pressure from Ms. Q’s attorneys. The warrant, which Ms. Q has contended she never knew existed, accused her of being involved in one of El Salvador’s violent street gangs — which the country’s Supreme Court had deemed “terrorist organizations.” The charge was apparently tied to an incident in 2016 involving a gang-related shooting outside a house in a small town on El Salvador’s west coast, where she’d been renting a room with her son, then an infant.

“Basically, [she] got swept up in the wrong place at the wrong time,” said Goettel of the incident that prompted the warrant. In fact, Ms. Q, who has consistently denied having any gang affiliation, said she was brutally beaten and threatened with death by a group of men who suspected her of cooperating with the investigation of the shooting, prompting her to flee that town and eventually the country.

And yet, as Goettel and her co-counsel proceeded to accumulate evidence in Ms. Q’s favor, including an affidavit from an attorney in El Salvador who reviewed the details of the case against her and found no actual evidence of gang affiliation or criminal activity, they found it incredibly difficult to escape the label the government had placed on her with a single unsubstantiated document.

For example, after reviewing the arrest warrant and evidence submitted by Ms. Q’s attorneys at a bond hearing in late July, an immigration judge in Laredo concluded that “none of the evidence in the record indicates that [Ms. Q] would pose a threat to national security or a danger to the community at large.” Nonetheless, the judge denied her request for bond, citing a concern that she might be a flight risk. At an asylum hearing in October, Ms. Q again denied that she had any gang affiliation or criminal background. The judge said he found her testimony credible but denied her request for asylum on other grounds.

As ICE continued to “dig in its heels month after month,” Goettel concluded that she needed to take the case outside the immigration court. In September, NIJC and others filed a lawsuit in federal court accusing ICE, DHS and others of violating Ms. Q’s due-process rights and requesting the “secure reunification of mother and child.”

Finally, in late November — eight months after their initial separation — a U.S. district court judge in Washington, D.C., ordered the immediate release and reunification of Ms. Q and her son.

“While we are overjoyed with the result, they should’ve been reunited much sooner,” Goettel told Yahoo News. “We shouldn’t have had to go to federal court in D.C. to get them back together.”

Goettel believes the case illustrates the Trump administration’s “scorched-earth policy when it comes to any gang affiliation.”

Ms. Q’s case is one of a handful in which ICE accusations of gang ties have been successfully challenged in federal court over the past two years, each one revealing a reliance on flimsy, unsubstantiated evidence.

“I think this is a thematic thing on the part of the administration,” said Stephen Kang, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union’s Immigrants’ Rights Project. “It’s been one way in which they’ve tried to justify their harsh enforcement tactics by saying that what they’re doing is going after gang members when, in reality, their efforts are a lot more sweeping and a lot less targeted than that.”

Kang was one of the attorneys involved in a class-action lawsuit on behalf of Central American teens arrested as part of Operation Matador, an ICE initiative launched in May 2017 by ICE to target alleged members of MS-13 and “other transnational criminal gangs” such as MS-13’s rivals, the 18th Street gang, in parts of New York’s Long Island and Hudson Valley regions, where both organizations have become active in recent years.

The operation, which as of March 2018 had resulted in 475 arrests, including 274 alleged members of MS-13, has received significant attention — both from President Trump, who has praised it, and from immigration advocates who argue that many immigrant youth were being wrongly accused of gang ties.

U.S. District Court Judge Andrew Hurwitz issued a preliminary injunction in the ACLU suit, known as Saravia v. Sessions, providing some basic constitutional protections for teenagers detained in the sweep. Kang says the suit disclosed some disturbing facts about the way ICE operated:

“In general, the pattern was that they came to the attention of local law enforcement somehow — either law enforcement directly encountered them or somehow they got information from the school about the kids — and then law enforcement referred them to ICE,” he said. But rather than produce arrest records, the government cited ambiguous evidence ranging from reported associations with known gang members at school to being seen wearing a certain type of sneaker, blue clothing and even rosary beads.

“I think that’s actually part of the issue is that their way of identifying gang members is so problematic and flawed, so even if they do have concrete criteria, they’re not very focused,” said Kang.

Under current U.S. immigration law, gang membership by itself is not grounds for deportation or exclusion. Still, even the slightest whisper of gang affiliation can have devastating consequences for immigrants.

And yet, despite the high stakes involved, a remarkably low standard of evidence is required for immigration to make such allegations. According to the DOJ’s Executive Office of Immigration Review, which oversees U.S. immigration courts, immigration proceedings are generally “not bound by the strict rules of evidence.”

Pretty much anything is admissible, including hearsay, as long as it’s “probative and not fundamentally unfair.”

According to ICE spokesperson Danielle Bennett, ICE classifies individuals as gang members if they admit to membership in a gang, have been convicted of certain gang-related crimes or meet two or more of the following criteria:

Subject has tattoos symbolizing or identifying a specific gang;

Subject frequents an area notorious for gangs and/or associates with known gang members;

Subject has been seen displaying gang signs/symbols;

Subject has been identified as a gang member by a reliable source;

Subject has been arrested with other gang members on two or more occasions;

Subject has been identified as a gang member by jail or prison authorities;

Subject has been identified as a gang member through seized or otherwise lawfully obtained written or electronic correspondence;

Subject has been seen wearing gang apparel or been found possessing gang paraphernalia.

“That’s the thing that’s so frustrating about gang membership, in particular… they don’t actually have to prove it,” said Marissa Montes, co-director of Loyola Immigrant Justice Clinic (LIJC) in Los Angeles, explaining that, in immigration proceedings, a person can be accused of gang membership or association without having been convicted of a gang-related crime.

“Basically anyone can be categorized as a gang member…. from an actual cholo who is gang- banging to his girlfriend that unfortunately is in the relationship with him to even a grandmother because she lives with him.”

Montes said that much of her work over the last few years has focused on the immigration consequence of gang allegations, whether they’re legitimate or not.

“This is actually not a new trend,” said Montes. “The government has always gone after people that they consider to be gang members or have gang affiliation; it’s that we’re just seeing it now at a higher rate.”

In most of the cases Montes has handled, gang allegations have been at least loosely based on some sort of documentary evidence, such as appearing on a state gang database. But when told about Nfor’s case, she said, “I don’t find it surprising that a [deportation] officer would feel empowered to say [she] can actually testify to someone’s gang membership based on tattoos.”

“It’s just incredibly atrocious,” she said of the allegations made against Nfor. “It just goes to show how ridiculous immigration proceedings can be because anything goes.”

According to the most recent data released by ICE, “During FY2018, ICE ERO removed 5,914 aliens classified as known/suspected gang members (5,872) or known/suspected terrorists (42), which is a 9 percent increase over FY2017.”

That’s just people who were deported by ICE last year. But lawyers have reported seeing a notable uptick in vague, baseless or outright false allegations of gang membership being used against immigrants in all areas of the immigration system. A survey of immigration attorneys in 21 states and the District of Columbia published in May 2018 by the Immigrant Legal Resource Center found gang allegations against adults and juveniles on the rise in immigration proceedings across the country, with officers often relying on vague, unsubstantiated evidence.

Attorneys have also reported, anecdotally, that gang allegations are being made more often outside immigration court, to long-term residents affirmatively applying for things like green cards, DACA renewal, citizenship and various other immigration benefits — an administrative process not involving a judge.

In response to a request for comment about this trend, DHS spokeswoman Katie Waldman said the Trump administration has “prioritized the removal of dangerous gang members, including MS-13, from our nation.”

Neither Bryan Cox, head of public affairs for ICE’s Southern Region, which includes the Georgia detention center and immigration court where Nfor’s case was heard, nor anyone from the agency’s national press office responded to requests for information or comment submitted last month. Since then, more recent attempts to follow up have been met with automatic replies explaining that, due to the government shutdown, all of ICE’s public affairs officers are out of the office and unable to respond to media queries “because we are prohibited by law from working.”

—————

Read more from Yahoo News:

2020 prospect Sen. Klobuchar: It’s ‘difficult to imagine’ voting for Trump AG pick

Someday, Donald Trump will be a former president. The mind boggles.

Despite denials, documents reveal U.S. training UAE forces for combat in Yemen

How the government closure is affecting Americans nationwide

Biden and Warren have a history. If he runs, it may come back to haunt him.

PHOTOS: Partial government shutdown continues as Congress and president fail to reach deal