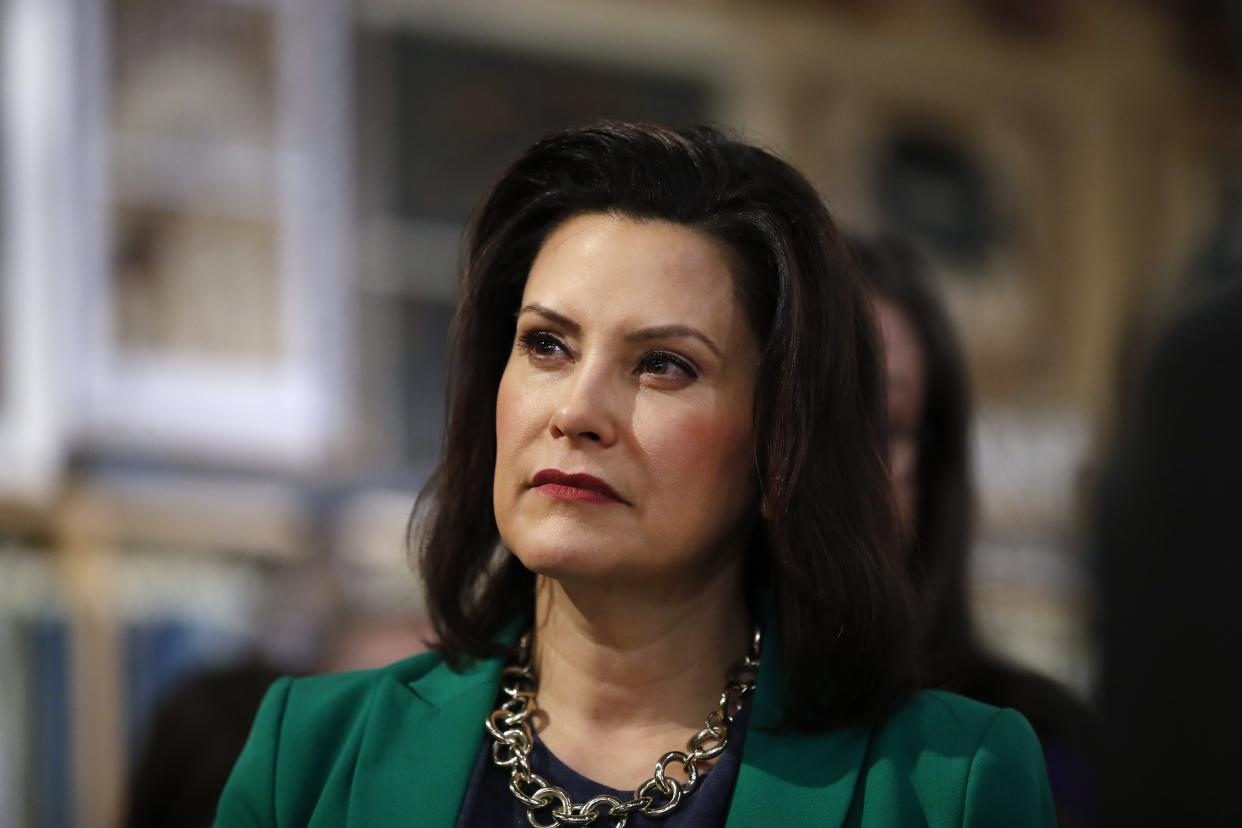

This Michigan Political Fight Should Matter To Democrats Everywhere

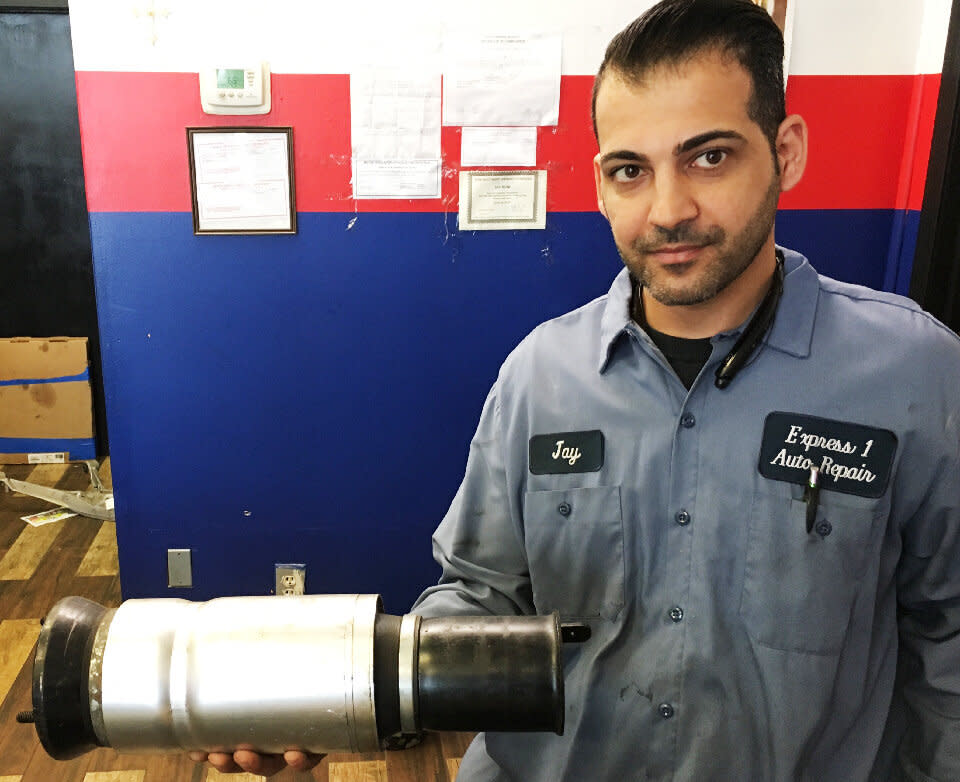

WARREN, Mich. ― Mechanic Jay Buni knows all about the “damn roads” that his state’s new Democratic governor, Gretchen Whitmer, has vowed to fix.

Buni is co-owner and operator of Express 1 Auto Repair, which sits near a pair of rutted streets that are among the five most dilapidated in southeast Michigan, according to a Detroit television viewer survey. His shop’s specialty is engine work, but he ends up handling emergency wheel and suspension repairs whenever bad weather means drivers don’t see the big potholes in time to swerve around them.

A customer’s Ford Taurus once fell into a gulley so hard that the impact propelled a strut up through the fender and into the hood, Buni said. He’d never seen anything like it in nearly a decade of being a mechanic. “Her car was totaled,” Buni remembered. “The roads here… they are the worst.”

Buni wasn’t exaggerating ― about the exploding strut story, which the shop’s co-owner confirmed, or the sad state of Michigan roads, which a series of independent studies has documented. The latest came in January, when a company that produces high-definition maps for self-driving cars issued a report on 5 million miles of roads across the country. It ranked Michigan’s dead last.

As a candidate last year, Whitmer tapped into frustration over those conditions, promising in every speech and media appearance to “fix the damn roads.” It was more than a specific policy pledge. It was a signal about the kind of governor she would be: a savvy, pragmatic leader who would get things done.

Now Whitmer has her chance to make good on her promise, and she has put forward a plan to increase annual road funding by more than $2 billion. But less than a year after literally mocking suggestions that such an initiative would require a big tax hike, she is calling for precisely that ― specifically, a three-stage increase in the gas levy that would raise it by 45 cents a gallon.

Michigan would end up with the nation’s highest fuel taxes and, so far, the public does not seem thrilled about the prospect. In a public poll from mid-April, 75 percent of Michiganders said they oppose the idea. Republican leaders in the state, who control the legislature, have been just as hostile.

“The proposal that she put forward is a nonstarter for our caucus,” said Lee Chatfield, the Republican speaker of the state House. “The people in our district cannot afford it.”

Whitmer’s tax proposal is just the opening bid in what everybody understands will be a long negotiation. But money to fix the roads would have to come from somewhere and that can’t happen unless some of the skeptics change their minds ― as Whitmer is urging them to do.

“This is not easy, but if it was, someone else would have done it already,” the governor said at an appearance earlier this year. “I was not elected to tell people what they want to hear. I was elected to solve problems.”

Michigan residents have a direct stake in how this debate ends and so does Whitmer, a rising political star who more than one pundit has said could run for national office someday. But even people outside of Michigan may want to pay attention, especially if they have a rooting interest in the Democratic Party’s agenda.

Pretty much everything Democrats talk about doing nowadays, from simple, relatively uncontroversial increases in school funding to sweeping, polarizing plans for single-payer health insurance, would require raising new revenue. The essential argument on behalf of these ideas is the same as Whitmer’s pitch on the roads: that the benefits people would see are worth the higher taxes they would pay.

There was a time in American history when this case wasn’t so difficult to make, because voters had more faith in government and Republicans were more open to taxes. But that was long ago. The country now seems stuck in a self-destructive cycle ― one in which funding shortfalls make public goods and services inadequate, fueling yet more cynicism about government’s ability to solve problems and making it harder to get the funding that these programs need.

It’s a cycle that has plagued Democrats for decades, especially in states like Michigan that frequently hold the key in national elections. Can Whitmer break it?

A Legacy Of Neglect From Washington To Lansing

Nobody disputes that Michigan has skimped on road repair spending. By 2015, the state was spending $171 per person on roads, according to a report from the nonpartisan Citizens Research Council of Michigan. That was barely half the spending level in Wisconsin, a state where the roads are subject to similar strains from climate and vehicle wear.

“It really doesn’t make sense, because our geography, our climate, our economy would all beg for an over-investment in roads,” said Eric Lupher, the council’s president.

State and local transportation agencies have reacted to this situation predictably, increasingly relying on patchy, temporary fixes and prioritizing emergency repairs over ongoing upkeep. Maintenance has fallen further and further behind, and the roads are constantly deteriorating.

The backdrop to all of this has been stagnant funding at the national level, where the gas tax, which pays for the U.S. Highway Trust Fund, has remained stuck at 18.4 cents a gallon since 1993. It would now be 31 cents if it had simply risen risen with inflation, as journalist Michael Tomasky notes in his new book, “If We Can Keep It.” But like all other efforts to increase revenue, raising the gas tax has become “undiscussable” in Washington, as Tomasky puts it.

The same goes for other efforts to finance infrastructure more generally. Major plans have been staples of Democratic agendas, going back to the proposals Barack Obama made when he was president, but after the one-time infusion of the Recovery Act ― passed in the first days of the Obama administration, in the midst of an economic crisis ― every one of them run into fatal GOP opposition.

And although infrastructure has been a fixture in the rhetoric of President Donald Trump, it has never been a serious priority. It’s been nonstarter with his putative GOP allies in Congress to the point that regular mentions of “infrastructure week” have become a running joke on Twitter.

The neglect has gotten so severe, and the road conditions so dire, that many states have reluctantly acted on their own. Frequently it’s been at the behest of business groups like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, whose members depend on good roads for supplies and shipping and which have enough sway with state Republicans to overcome the party’s ideological opposition to taxes.

It happened that way in Michigan, where in 2015 the GOP legislature begrudgingly approved a modest gas tax increase proposed by then-Gov. Rick Snyder, an old-school, business-oriented Republican.

Snyder had been trying to get road funding for a while. His first bid was a complicated package that included a sales tax increase, which voters overwhelmingly rejected when it appeared as a ballot measure. That diminished his leverage, and when Snyder finally got the legislature to go along with a different road funding package, it was well short of what the state needed.

Since then, several independent experts and panels, including a bipartisan commission Snyder appointed before leaving office, have concluded that properly maintaining the roads would require additional spending of at least $2 billion a year. That is right in line with what Whitmer is seeking.

Michigan’s Roads And Legislature, By The Numbers

Whitmer has done her best to quantify the price of inaction, citing a study from TRIP, an independent think tank that focuses on surface transportation, showing that poor road conditions cost a typical Michigan driver $646 a year. Whitmer’s plan wouldn’t eliminate that cost, but it could reduce it by a few hundred dollars. That is more than what the typical consumer would end up paying in new gas taxes, according to estimates from the Whitmer administration and some independent analysts.

And the $646 figure may actually understate how much poor roads cost Michiganders because it doesn’t take into account the expense of more accidents and greater congestion. Nor does it capture the economic benefits the state gives up because officials don’t have the money to update roads in ways that would boost growth.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

“The striking thing about Michigan, the thing that’s different, is that right now they are focused almost entirely on preservation, fixing things already there,” said Rocky Moretti, TRIP’s director of policy and research. “When you go to other states, they are also talking about new interchanges, improving traffic flows, new things they are building to encourage economic development.”

The logic is compelling. But, especially after the last tax hike, many voters don’t believe that another, bigger one will make a difference. Just last week, the secretary of transportation got a chilly response when he pitched the Whitmer package to an audience in Sterling Heights, north of Detroit. “They’re going to have to prove to me that this is going to work,” one attendee told an MLive.com reporter.

Whitmer’s task is even harder because she is operating inside a political system that leaves her and her party at a structural disadvantage. Democrats won every major statewide contest in November and even managed to flip a pair of long-held Republican congressional seats. But Republicans easily held their majorities in the legislature because the districts are so heavily gerrymandered in their favor, giving more conservative, rural districts extra influence.

The days of gerrymandering are finally coming to an end in Michigan, thanks to a successful 2018 ballot initiative and a 2019 federal court ruling. But neither is taking effect right away, which means Whitmer is stuck with this legislature and its Republican majority for at least the next year and a half.

Whitmer has said she’ll consider alternative funding mechanisms if Republicans, who say they are open to new revenue in principle, would just propose one. So far, they haven’t. Susan Demas, a veteran political observer and editor of the new, left-leaning Michigan Advance, said that attitude is indicative of the way the party has changed in Michigan.

“The current philosophy of the Republicans is a lot more hard-line than it used to be,” Demas said. “Republicans have to drive on these roads too, they hear from their constituents. … But they really don’t want to give the governor the win.”

A Test For Democrats ― And For Democracy

Whitmer’s predicament should sound familiar to Democrats around the country. They know first-hand how gerrymandering, the overrepresentation of rural districts, public skepticism of public programs, and extremist Republicans can make passing any major legislation difficult.

None of which is to say Whitmer can’t succeed. GOP proposals to fix the state’s no-fault auto insurance system, which leaves residents with some of the nation’s highest rates, are among the moving political pieces in Lansing right now. Although Whitmer has said she agrees with Republicans on the need for reform, she has very different ideas on how to do it ― which means, just maybe, there’s a deal to be struck.

“I think she would accept some stuff on auto no-fault and the budget that she wouldn’t accept otherwise, in order to get a lot of what she wants on infrastructure,” said Adrian Hemond, a partner and CEO of Lansing-based consulting firm Grassroots Midwest.

But Whitmer has only a few months to close the deal, because budget negotiations have to wrap up in time for the new fiscal year, which starts Oct. 1. The chances of a gas tax passing after that, with the next election approaching, are virtually nil.

And Demas, for one, said Whitmer has reason to hold out for the full funding ― yet another half-measure is likely to leave voters disappointed and exhaust whatever patience they have for more tax increases.

“Doing half a loaf might be worse politically than not doing anything,” Demas said.

“Texas-size pothole” on I-69 causes flat tires and a multi car accident in mid-Michigan https://t.co/7rrhGE6bTH

— Chad Livengood (@ChadLivengood) May 15, 2019

If Republicans won’t go along with full funding, Whitmer could refuse to sign the budget, provoking a showdown and maybe even a shutdown. She could also give up on the legislature and try to have the state borrow the money through a bond measure. But that’d present its own fiscal complications and would require voter approval.

Her other recourse would be to attack Republican legislators for their opposition, in the hopes that voters hold them responsible for letting the roads deteriorate and elect a legislature in 2021 willing to make the investment. Some GOP allies have warned party leaders not to assume they would survive such a fight.

“If the Republicans don’t deliver and are seen as overly obstructionist on fixing the roads, I think they’re going to be in for a tougher road in 2020 — and I think they realize that,” Sandy Baruah, CEO of Detroit’s regional Chamber of Commerce, told Crain’s Detroit Business.

Still, flipping the legislature would likely require a surge in support for Democrats even bigger than the one that got Whitmer elected. That’s asking quite a lot, especially for a governor better known for working the system than rallying activists. Filling potholes may seem like the most straightforward, least controversial thing that government does. But these days, even the easy things in politics are hard.

Related Coverage

House Democrats Kick Off Push To Tackle Infrastructure 'Crisis'

Republicans Say Trump's Infrastructure Plan Should Be Deficit-Neutral

Trump Promises Louisiana A Badly Needed Bridge, But Only If He Gets 4 More Years

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.