Can the Government simply print money forever?

Getting hold of £300bn is not easy at the best of times. Even for the Government, which may need to borrow that much this year to keep on spending in the coronavirus-ravaged economy, it could present some serious challenges.

Yet so far investors seem desperate to hand their cash to the Treasury.

Last month it borrowed a record amount in financial markets, selling bonds to investors who get their money back plus interest when the bond matures.

In May and June it expects to hoover up another £180bn. This is a pace of borrowing never seen before, as tax revenues slump and demands on the public purse soar. At the same time it needs to refinance old borrowing, as bonds issued in years gone by mature and are replaced with new debt.

Despite this furious pace, HM Treasury has had no difficulty in drumming up interest in its loans.

Just today the Debt Management Office borrowed £3.25bn in a five-year bond.

Anyone buying it can expect an interest rate of around 0.04pc – less than half than the Bank of England’s 0.1pc base rate, and far below inflation’s 1.5pc. Yet investors flooded in. More than £8bn was offered to the Government.

'Safe haven' appeal

Why are they so keen to buy these bonds that pay negative real returns? Partly it is the lack of alternatives. The UK and the world are in a recession, so "safe haven" assets are in demand.

Low returns and high risks elsewhere, such as in the choppy stock market, make bonds appealing.

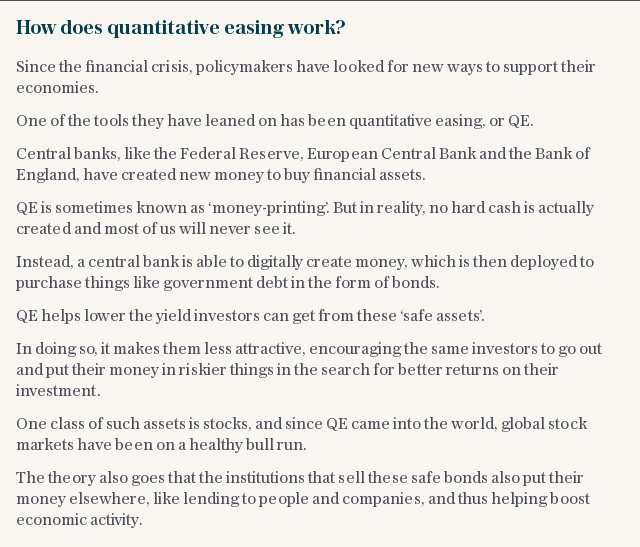

On top of that, the Bank of England is buying another £200bn of Government bonds from investors in the form of quantitative easing (QE). It does not buy directly from the Government, but the net effect is that it is printing money equivalent to a large chunk of this new debt.

That means the financial markets do not have to bear much of the extra debt, supporting the Treasury’s ability to keep borrowing.

Economists expect another £100bn of QE to be forthcoming at next month’s meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee.

Andrew Bailey, the Bank of England’s Governor, has indicated this is a sensible approach.

“One of the reasons that the Bank of England is obviously acquiring a much larger stock of government debt… is that we can help to spread over time the cost of this thing to society and that to me is important. We have choices there and we need to exercise those choices,” he said in an interview with ITV.

Money isn't free

None of this makes borrowing "free". Debt interest payments cost the Government around £50bn per year. However, it is still cheap in relative terms.

The debt-interest ratio measures the share of Government revenues spent on servicing its debt - that is, paying the interest on its loans.

Back in 1947, when the UK was labouring under vast war debts, almost one-sixth of all receipts went straight back out the door to pay interest.

Between the 1950s and the 1980s this fluctuated between around 6pc and 11pc.

The national debt fell as a share of GDP over the decades, and combined with lower interest rates that took payments down to below 5pc of revenues by the eve of the financial crisis.

Debt exploded in the credit crunch, booming from just over 30pc of GDP to around 80pc now. Yet a funny thing happened to the cost of maintaining that enormous mountain of debt.

After a brief rise, it plunged to record lows. Last year the debt-interest ratio fell to below 4pc for the first time ever.

Ever-lower interest rates make higher debts sustainable, for now at least.

Most City economists expect the Bank of England to hold interest rates at 0.1pc until at least the end of next year, while financial markets are trading on the assumption the base rate could go negative later this year.

The UK has also successfully locked in low costs by issuing unusually long-dated bonds, reducing the risk that any short-term spike in market interest rates will derail the national finances.

But can it go on forever?

QE has downsides too. It has not led to surging consumer price inflation as feared when it was launched in the financial crisis, but it can push up asset prices.

Nor is it the same as "monetising" debt – printing money to pay the bills – because it can, in theory at least, be reversed by selling the Bank of England’s bond holdings later, and is determined by independent central bankers who use QE, in large part, to target inflation and keep markets steady.

It still seems unfeasible to keep on printing money to fund ever-greater levels of borrowing year after year, as the newly created funds would lose any link with real economic activity. Bailey has noted that central banks will have to think hard about the way they manage their rapidly growing balance sheets in future.

What is possible in a crisis is not sustainable in "normal" times. What seems more plausible is that a few years of high borrowing can be supported by QE, low rates and keen investors.

The national debt could plateau at a level somewhere a little above 100pc of GDP quite comfortably.

Over time it could eventually come down as a revived economy pushes up GDP and so lowers the burden of debt. This should avoid the ratchet effect where debt rises in every recession but never falls in the good years.

Alternatives such as tax hikes have already provoked a fierce reaction from economists and business groups warning it could cut off any post-pandemic recovery and so trash the public finances in spectacularly counter-productive capacity.

The key for the Chancellor will be to convince markets that borrowing like mad now will protect the economy and give it a long-term boost, and in doing so will ultimately keep a lid on the debt burden over the next five to 10 years.