Gov. Cox unveils recommendations to create new clinical paths in behavioral health

Utah Gov. Spencer Cox wants changes in the licensing of behavioral health professionals in the state.

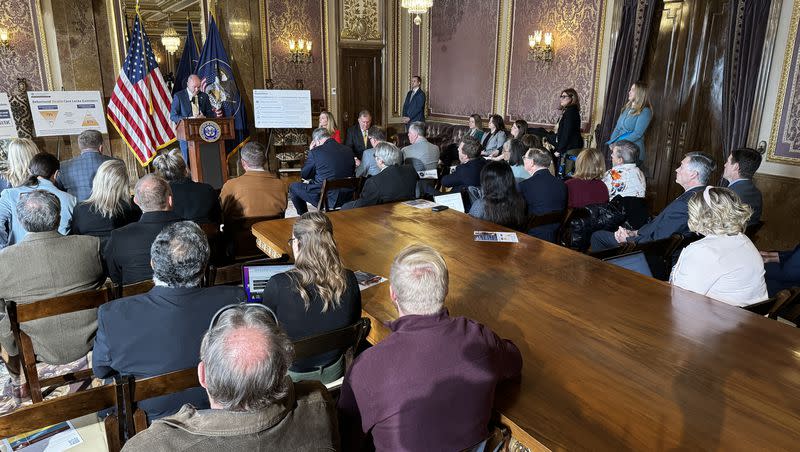

“Unfortunately, far too many Utahns who are trying to access and find mental health services are unable to get the care that they are looking for,” Cox said during a press conference Tuesday at the Capitol

Cox listed long wait times, the out-of-pocket costs and the difficulty to find providers as barriers to mental health care.

The Beehive State is “committed to tackling the mental health crisis from every angle possible,” and licensing is one area where Cox said changes can be made.

Calling it “a big first step in allowing more qualified therapists and behavioral health professional workers to get licensed in our state,” Cox said the goal of the recommended changes around licensing are to address the ongoing behavioral health crisis.

“We are seeing too many of our friends and neighbors, our children and our family members that are being touched by mental concerns,” he indicated. Pointing toward high depression and suicide rates across the country, Cox said the Utah Department of Commerce’s Office of Professional Licensure Review worked closely with the Legislature to find a way to increase access to mental health services.

Margaret Busse, executive director of the Utah Department of Commerce, said that there is a “chasm” between the people who need mental health services and the amount of workers qualified and available to provide these services.

Around 530,000 people in Utah are currently able to receive behavioral health care, she said. There are still anywhere between 200,000 and 500,000 people with diagnosable conditions who do not have access to the health care they need.

Across the medical field workforce, around one-third had a master’s degree or higher and the remaining two-thirds were at the bachelor’s degree level or lower. But that’s different across the behavioral health care workforce, Busse explained. Around three-quarters of that workforce has a master’s degree or higher.

“We don’t have a good career ladder for folks to get into it,” Busse said. After reviewing the licensure regulations, she said they found there were areas where “it imposed a burden that really didn’t have a benefit to consumers.”

To get more people into the workforce, the reviewers recommended the creation of “a new behavior health technician certification based on a one-year academic program.”

Another recommendation the reviewers had is to make it an easier process for a person with a bachelor’s degree to get licensed.

“There are very few of the bachelor’s level licensed professionals in behavioral health — most of them are coming from social work,” Busse said. “But we think we can do better by expanding that.”

Pointing toward the number of people with bachelor’s degrees in psychology, she said that without getting an advanced degree, it can be difficult for that group of people to follow a clinical path.

In lieu of taking national standardized exams, Busse said the reviewers are recommending that therapists train people on the job and that training can act as a substitute.

“We’re also proposing to expand the scope of practice for certain practitioners, broadening their ability to do more things, particular for bachelor’s degree level folks,” Busse explained. “So that they can do things like monitoring treatment plans and providing manualized interventions and keep therapists — the one that are highly trained — doing the things that just they can do: life psychotherapy, life diagnosis, those kinds of things.”

To address potential safety concerns, the reviewers proposed criminal checks to therapists and other safety measures.

Related

Jeff Shumway, director of the Utah Department of Commerce’s Office of Professional Licensure, has pointed out before that Utah ranks above the median number of reports per behavioral health licensee and there may be some already existing issues with supervision.

“So you can think of this as the archetypal safety issue is someone who’s recently licensed in private practice working in isolation. But we think some of what’s going on in safety is we have relatively lax supervision, both in law and rule and by practice in the state of Utah,” Shumway said. “We think we also have a lot of folks early career who are going straight into private practice, which has its own dynamic. That has to do with insurance and other things.”

The final recommendation Busse mentioned is creating a unified board. “Right now within our division of professional licensing, we have several boards and they’re all occupation focused,” listing off different boards like marriage and family therapy as well as a board for social workers. “We’re saying we need all of you to come together in a unified board.”

Sen. Curtis Bramble, R-Provo, also weighed in at the press conference. “Over one-third of our workforce, ladies and gentlemen, has to have some type of a license. And the challenge with licensing is if we overregulate, we prevent access.”

Calling it a “balancing act,” Bramble said Utah is engaging in “a unique experiment” that he believes is promising. “We looked at all the licenses and it’s been an intense study, but it’s been dispassionate. It’s been unbiased. It’s not under the typical political class or lobby class or the advocates.”