GOP Board Whipped Up Homeless Hate. Then a Man Was Murdered

In January, the Board of Commissioners in Flathead County, Montana, proclaimed that the homeless had become a big problem in the little town of Kalispell due to charitable efforts to shelter and feed them.

“Providing homeless infrastructure has the predictable consequence of attracting more homeless individuals,” read a preposterous letter signed by the three members, all Republicans. “When a low-barrier shelter opened in our community, we saw a dramatic increase.”

The letter progressed from icy hearted to paranoid.

“Using social media and smartphones, these wanderers are well-networked and eager to share that Kalispell has ‘services’ to serve their lifestyle,” it said. “Make no mistake, it is a lifestyle choice for some. In fact, many of the homeless encountered in our parks, streets, and alleys consist of a progressive networked community who have made the decision to reject help and live unmoored.”

The “low-barrier shelter” in question is the Flathead Warming Center, which opened in October of 2021.

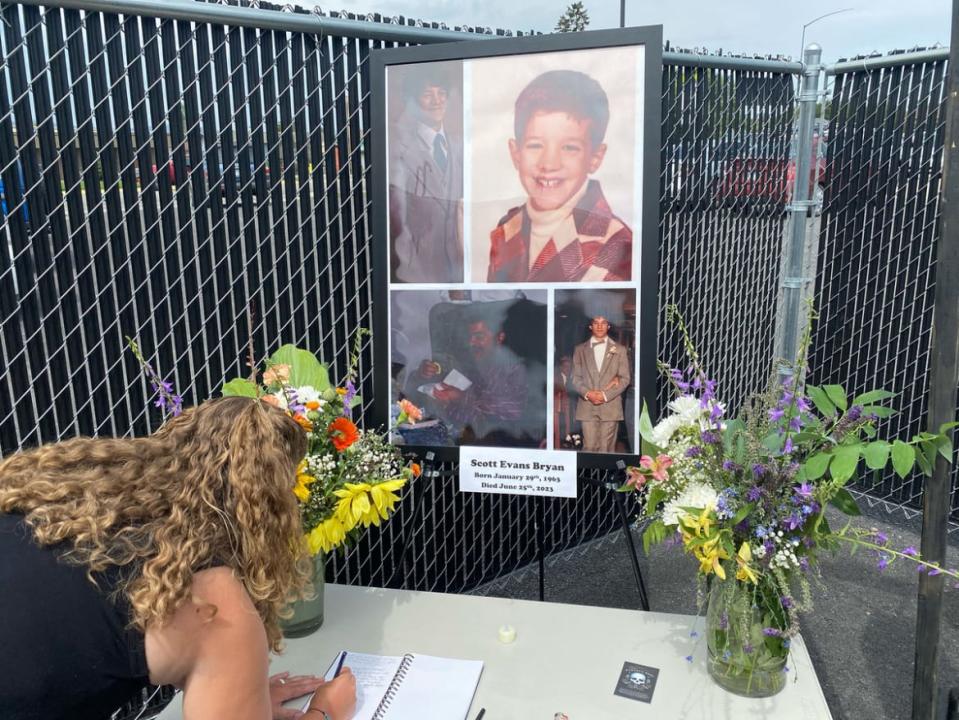

On Monday, the center hosted a memorial for a one-time resident who was beaten to death on June 25, the most serious of recent incidents involving domiciled townspeople and the homeless.

The suspected killer, 19-year-old Kaleb Fleck, is free on bail, thanks in part to a longtime white supremacist who has in the past sought to screen Holocaust-denying movies in the town library. Fleck has pleaded not guilty in the case.

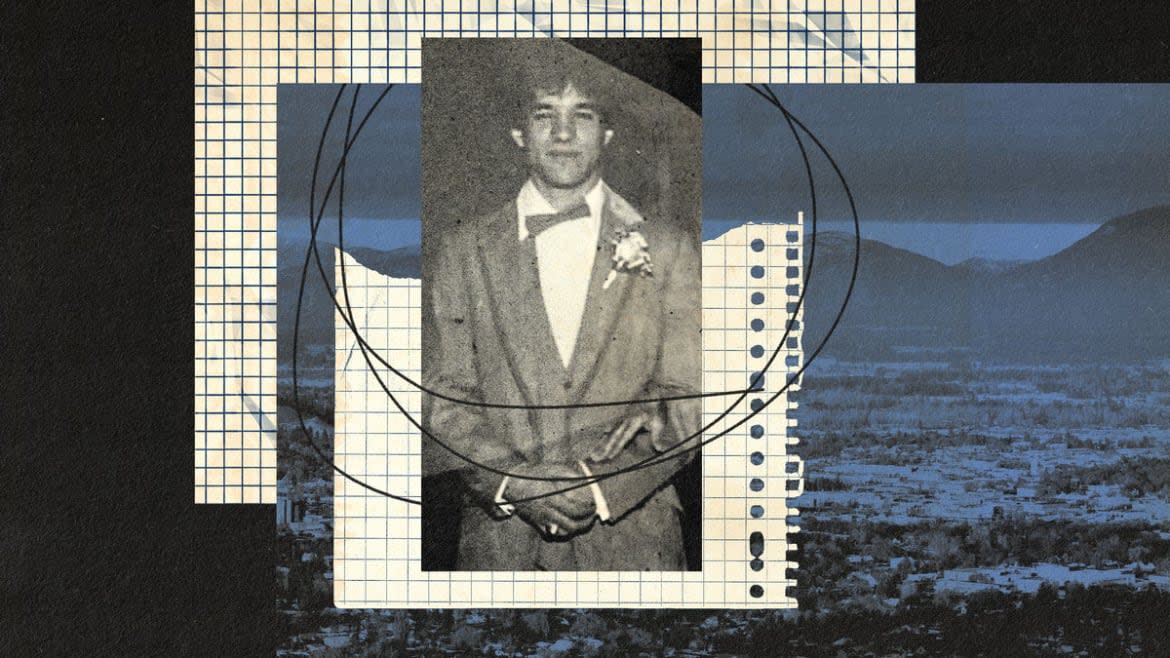

The victim was 60-year-old Scott Bryan, who did not have a cellphone or access to social media.

Bryan was found unconscious in a parking lot at 2 a.m. An affidavit filed with the court says that a female witness showed responding officers a video that recorded an exchange between Fleck and another local teenager named Wiley Meeker at the time of the attack.

“The camera pans between Fleck and Scott’s body lying motionless on the ground,” the affidavit says. “The eight second video depicts Meeker stating ‘You f-cked that guy up, dude,’ and Fleck responding, ‘Step up. Step up b-tch.’”

The memorial for Bryan was supposed to be held in the parking lot where he was killed, but liability concerns forced the service to be moved to the nearby Flathead Warming Center, where Bryan had sought shelter from the cold during his first and last winter as one of the unhoused. Relatives who live out of state were unable to attend, but sent photos of Bryan in better days.

A picture from the memorial service for Scott Bryan.

“There’s a picture of him at prom,” Tonya Horn, the executive director of the center, told The Daily Beast. “I often wonder what it would be like if our homeless population could carry around a picture of themselves before maybe illness took over or before they experienced the trauma that they have in their life. If they carry pictures of what they maybe used to look like before the plight of homelessness, would we treat them differently?”

Along with the prom picture is what looks like an elementary school photo of a smiling, fresh-faced Bryan with his whole life ahead of him. There is no hint that later years will find him ill with cancer and given to frequent epileptic attacks as a result of a head jury suffered in a motorcycle accident that left him with a plate in his head.

His misfortunes were compounded by homelessness in recent months. He appeared at the Kalispell library in early April with lists of housing websites he had obtained at the Community Action Partnership a block away.

“He didn’t know how to use a computer,” recalls library worker Annica Stivers. “He didn’t have an email. He didn’t have a phone.”

Stivers said she spent an hour helping him sign up for housing.

“He hadn’t been homeless before, this was like his first stint at being homeless,” Stivers recalled. “He wasn’t one of these people who’s trying to live on the street. He did not want to be on the street.”

He had stitches in his bald head that he told her were from falling off a top bunk in the shelter, Stivers said And that was just the latest of many woes.

“My first sense of him was kind of the same as like anyone who tells you a tragic story, you kind of wonder like, ‘What are they trying to get out of me?’ But he never asked me for anything,” Stivers said.

Over the days ahead, he sometimes stopped by the library to chat. Bryan worked for a time as an overnight stocker at a grocery store and got a hotel room whenever he could. But his frequent seizures caused him to lose his job. He was added to a waiting list for assisted living and was nearing the top before his death.

“He wasn’t excited about it because he didn’t consider himself like old or disabled,” Stivers said.

Meanwhile, the streets were getting meaner. Bryan came in to see Stivers a few days before he was killed.

“He’d been staying on the streets for I think three nights at that point,” she told The Daily Beast. “He told me he was scared and he hadn’t been sleeping because it’s just not safe. There’s people out there messing with him.”

She had not yet heard talk of teenagers who were said to have broken a homeless man’s collarbone and killed a homeless couple’s dog. But she could tell Bryan was in rough shape.

She reminded him that the warming center was still open three times a week for a meal and a shower and laundry. And he was still on the waiting list for the assisted living facility he called “the old folks home.”

“You can make it through this,” she recalls telling him. “You’re gonna go to that old folks’ home, as you called it, and it might be boring, but you’ll have a bed and you can get back on your feet.”

Bryan prepared to depart the library.

“If I see you again…” he said by her recollection.

“What the hell are you talking about?” she asked. “Where are you going?”

“I don’t know if I’ll see you again,” he said.

“I'll see you again, Scott,” she said. “I’m not going anywhere.

He headed back out to the street.

“Oh, you’ve got a friend there?” the security guard said.

“Yeah, that’s my buddy, Scott, she said.

Stivers was home several nights later, when her husband told her he saw something on social media about two local teenagers being arrested for beating a homeless man to death.

“I was like, ‘Who? What’s the name? “ she remembered. “He told me, Scott Bryan.’ And I was like, ‘Oh my God, he’s my buddy.’”

An affidavit filed by the police states that officers had found Bryan sprawled face down behind a Conoco gas station.

Both Fleck and Meeker were arrested for intentional murder. But the charge against Meeker was dropped.

“The officers rolled Scott to his side and noted that he was bleeding profusely,” the affidavit says.

Scott was transported to the hospital where he was pronounced dead.

“An officer present noted that Scott had severe facial and head trauma, including lacerations and exposed bone,” the affidavit says. “The officer noted that it appeared that Scott’s nasal cavity had been crushed.”

According to the affidavit, police interviewed Fleck and Meeker separately.

“Both admitted to being present at the gas station and sitting in Meeker’s truck,” the affidavit says. “Fleck admitted exiting the vehicle and assaulting the man, later identified as Scott Bryan. Meeker stated that he pulled Fleck away from Scott and then they left the scene.” Both teens were initially charged with murder, but charges against Meeker were dropped. Fleck pleaded not guilty and was freed after posting $500,000 bail with the help of two relatives and Zachariah Harp, who has been identified as an extreme white supremacist by the Southern Poverty Law Center and Montana Human Rights Network. Harp has been tied to the racist, antisemitic Creativity Movement, whose motto is “what is good for the white race is the highest virtue, and what is bad for the white race is the ultimate sin.” Harp is the son of a former state senator John Harp. Neither Fleck’s lawyer nor Zachariah Harp could be reached for comment.

During the public comment session of the June 29 meeting of the Flathead County Commission, Stivers addressed the three authors of the latter that describes the homeless as an insidious network of progressives who have chosen their lifestyle.

“I’m here today to talk about my friend Scott, who was beaten to death Saturday night,” she said. “I’ve been having a hard time grieving his death.”

She fought tears as she continued.

“Scott did not want to be on the street. He did not choose homelessness, and he worked every day to get off the street.”

She told the commissioners that she did not blame them for what happened to her buddy.

“But the three of you are in a unique position where you can help people like Scott to make sure this doesn’t happen again,” she continued. “I’m speaking up for Scott today, so that when you picture the homeless in your mind, you don’t see the group that you wrote about in your open letter in January. But you see people, for the individuals, they are, many of whom are very deserving of help.”

Cassidy Kitt of the Community Action Partnership also spoke. Her organization provided Bryan with the lists of housing possibilities as well as assisting him with getting doctor appointments. Her mother also worked to assist the homeless and her father is a counselor. She stood as proof that Flathead County and Kalispell have a tradition of compassion and socialism in contrast to the racism represented by the likes of Harp.

“I think at the very least, we could stand up and have a really strong public statement from the commissioners that says, ‘Hey, this isn’t cool. This isn’t reflective of our community values,” she told the letter’s authors. “And I really hope that this is an opportunity to exercise your collective voices and to say, ‘I stop with the violence. We can come up with a plan. We can work on our plan collectively, collaboratively, and do it in a fiscally prudent way.’ But at the first step, I want for people to feel safe.”

The board issued a statement in response to a Daily Beast request for comment.

“What took place that weekend was tragic. Our thoughts and prayers go out to the families and friends of all who were affected by this incident and who are grieving. We cannot comment on what led to this tragedy as it is still under investigation by KPD and the Flathead County Attorney, except to say that violence against anyone has never been condoned or suggested by this County Commissioner Board.”

In an interview with the Daily Beast, Kalispell Police Chief Jordan Venezio confirmed that his department has several active cases where the homeless have felt threatened or harassed. He said that his officers have been meeting with homeless people on how to stay safe and secure police assistance if they need it.

“This is a new challenge for our community and everyone’s just trying to find their way and deal with it and try to take care of people,” Venezio said.

At Monday’s memorial service, a memory book was set out for Stivers and other buddies to sign.

“We all miss you a lot,” she wrote. “You touched a lot of lives. “I’ll see you in the next life.”

A local brewery donated food. Kitt brought flowers from her garden and those of neighbors. They were set before the photos of Bryan, including the one from when he was a youngster, before all that was to come.

“I was crying and laughing at the same time, “ Stivers said.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.