GM strike exposes anti-worker flaws in US labor laws. Companies have the upper hand.

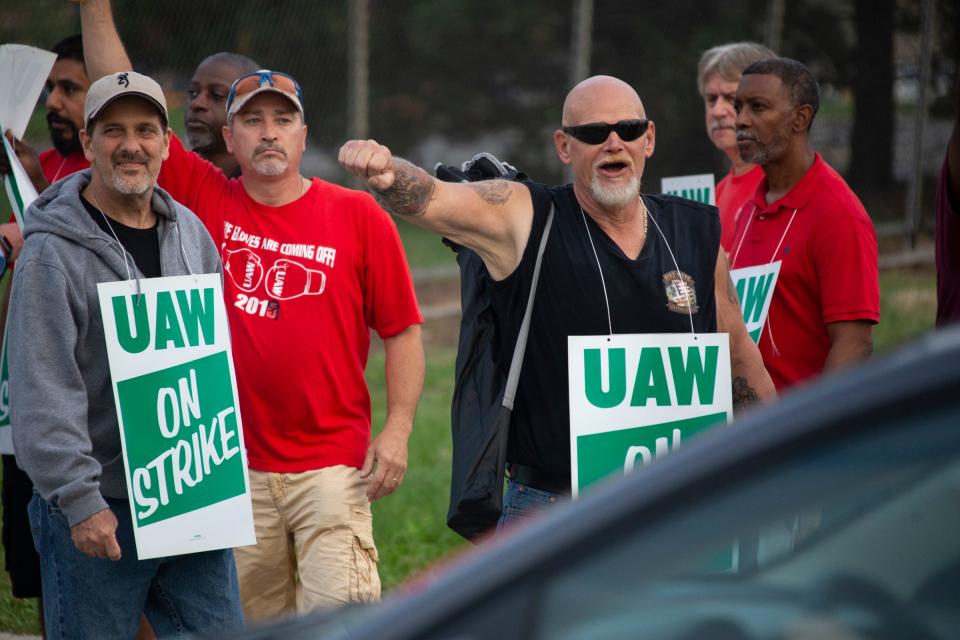

Nearly 50,000 auto workers at 55 General Motors plants nationwide walked off the job on midnight Monday morning, demanding a fair share of the $8.1 billion in profits GM made last year. The workers also want to reduce temporary work, and they want a guarantee that key plants will remain open. In short, they are fighting to maintain good manufacturing jobs.

Auto jobs were not always good jobs. Back in 1936, when Michiganders organized the first strikes against GM, autoworkers were paid little and had few rights. They endured violent police repression and court injunctions before winning union recognition.

The current GM strike once again highlights the courage of United Automobile Workers members — and their willingness to fight for the American dream. But this strike also underlines the extent to which our labor law regime is broken and in need of fundamental reform.

Contract workers and temps

Over the last decades, the Big Three have increasingly subcontracted out their work to non-union parts suppliers whose workers earn far less than the union rate. Particularly at the non-union suppliers down South, safety violations are rampant, wages are about 70 cents on the dollar compared to those earned by auto workers in Michigan, and hours are punishing. The Big Three have also hired more temporary workers, who earn lower wages, receive fewer benefits, and lack stable employment.

GM needs to respect workers like me: I've worked for General Motors for 25 years. I'm on strike because we're done sacrificing.

Meanwhile, foreign automakers like Honda, Nissan, Toyota, and Volkswagen have entered the U.S. market, operating their plants with non-union workers and paying their workers, on average, about $10 less per hour than UAW members receive. The non-union companies rely even more heavily on temporary employees and on parts suppliers with horrendous safety records.

Whatever contract the UAW members and GM eventually reach, it is unlikely to solve the downward pressure on employment that plagues the auto industry. To address that, and to secure the future of good jobs generally, we need a labor law system that guarantees bargaining rights for all workers in the sector.

Incentivizing the union-busters

To be sure, some of the threat to good manufacturing jobs is due to globalization and automation. But a lot of auto manufacturing jobs still exist in the United States. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that nearly a million people work in the industry. Yet our law permits a race to the bottom among those jobs. Unlike labor law in most industrial democracies, U.S. labor law does not create a system of sectoral bargaining through which fair terms are negotiated and apply to all workers and companies in an industry. Instead, U.S. labor law channels organizing and bargaining to the level of the individual worksite and the individual firm.

This approach encourages firms to compete by busting unions and lowering wages. So when workers at the non-union auto companies have sought to unionize, they have been met with threats and intimidation. Pro-union workers at Volkswagen, for example, report being put under surveillance and required to attend mandatory anti-union meetings, including one at which the governor of Tennessee personally urged workers to reject unionization.

When a group of Volkswagen workers did vote to unionize, the company refused to bargain, stalling in the hopes that, once dominated by President Trump's appointees, the administrative agency in charge of reviewing the case would switch its position, giving into management demands.

In short, a worksite-based bargaining system incentivizes employers to resist unionization. Moreover, even if workers succeed in organizing at the firm level despite intense employer resistance, bargaining with a single employer makes little sense in today’s economy. How can workers at the small companies that supply the big automakers with parts get a fair deal if they aren’t negotiating directly with the auto companies? Even unionized workers end up fighting an uphill battle: They have a collective voice in one worksite, or within one firm, but that is just not enough to limit downward pressure on employment, wages and benefits.

Fighting scale with scale

By contrast, in countries where a system of industrial or sectoral bargaining exists, workers and employers throughout the industry get together to agree on a fair deal for all. Under most sectoral bargaining systems, individual groups of workers and individual firms can still negotiate terms above the sectoral minimums and can still agree on more detailed work rules, But everyone has assurance that basic, fair standards will apply to all workers in the industry.

Going on strike punishes students: My special needs students needed their teachers in the classroom — not on the picket line

As a result, companies are forced to compete based on their technological innovation, their excellent service, and their management skill — but they don’t get to compete by cutting wages or busting unions. Indeed, Volkswagen reports having a good relationship with the German unions who bargain at the sectoral level. Not surprisingly, researchers have found that broad collective bargaining coverage tends to reduce economic inequality, as well as disparities in pay along dimensions of race, gender, and ethnicity. Everyone throughout the industry is entitled to fair conditions, no matter what their background.

In the last few years, growing worker movements have begun to demand changes in our flawed labor system by organizing on an industrial scale instead of just at individual work sites. Fast-food workers, domestic workers, ride-share drivers and others have been protesting for fair wages and a union for all workers in their industries and their communities. Teachers in red states and blue states alike have been striking for decent pay and high quality education for their students, not just in their own schools, but in all schools in their cities and states.

Now the auto workers are taking a stand, putting their own livelihoods on the line to defend what has long been the American Dream. Public policy should follow — it’s time for a new system of labor rights.

Kate Andrias is a professor of law at the University of Michigan Law School. This column originally appeared in the Detroit Free Press.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: GM strike: US labor laws put automobile workers at a disadvantage