Global warming made Australia's record-breaking, sizzling summer 50 times more likely

Millions of Australians just endured a sizzlingly hot summer, with three blistering heat waves enveloping much of southeastern Australia during January and February sending temperatures soaring as high as 48.2 degrees Celsius, or 118.7 degrees Fahrenheit.

New South Wales, located in southeastern Australia, had its warmest summer on record, with numerous temperature milestones shattered in Sydney, Brisbane and Canberra, among other locations.

SEE ALSO: The atmosphere has forgotten what season it is in the U.S.

Now a new quick-turnaround analysis from an international group of climate researchers found direct ties between global warming and this summer's heat. In completing the study, the researchers utilized the computing power of hundreds of volunteers' laptops and desktops worldwide, through a project known as weather@home.

January 2017 saw the highest monthly mean temperatures on record for Sydney and Brisbane, and the highest daytime temperatures on record in Canberra, the study, produced by the world weather attribution program at Climate Central and other institutions, found.

Image: Climate central

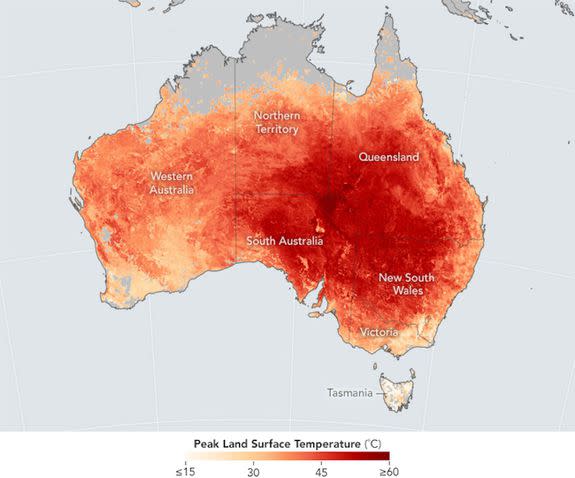

In many areas of New South Wales, temperatures topped out at higher than 45 degrees Celsius, or 113 degrees Fahrenheit, during the heat's peak on Feb. 11 and 12.

The duration of the heat wave was particularly noteworthy, with Moree, New South Wales, enduring 52 straight days with temperatures exceeding 35 degrees Celsius, or 95 degrees Fahrenheit, which set a record.

The study found that the regional record hot summer "can be linked directly to climate change." To reach this conclusion, researchers used methods that have been established in the peer reviewed scientific literature, such as by simulating the hot summer in the presence of planet-warming greenhouse gases and without them and comparing the likelihood of its occurrence.

Australia's annually averaged temperature has warmed by around 1 degree Celsius, or 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit, since 1910, according to the Bureau of Meteorology.

The team, including scientists at the University of Melbourne and University of New South Wales, also analyzed observational data, and both methods led to the conclusion that average summer temperatures like those seen in 2016-2017 are now 50 times more likely to occur than they were before global warming began.

Even worse, the study found that in the future, a summer a hot as this one is likely to happen once every five years, compared to once every 500 years prior to global warming.

Image: nasa

"Our results are certainly in line with what we have observed around the world in heat waves and their trends," said Andrew King, a climate extremes research fellow at the University of Melbourne, in an email. He said the results are "also in line with what we would largely expect to see as the overall climate warms."

Although the analysis itself is not yet peer reviewed, King said its reliance on peer reviewed methods adds credibility to the conclusions.

"By looking at multiple methods and regional to local scales we have confidence in our findings," he said. "The methods we have used here are all peer-reviewed so we can be confident in the results."

In addition to the regional analysis, the researchers also investigated how the odds of such a hot summer has shifted on a local level for Sydney and Canberra specifically.

Here, their results were more mixed due to the greater uncertainties involved with looking at smaller geographical scales. In Canberra, the researchers found there has been a 50 percent increase in the likelihood of a three-day heat wave such as what occurred from Feb. 9 to 11 of this year.

However, the analysis found no clear human-induced trend in Sydney for such a short-term heat event, since the decades-long signal of global warming couldn't be separated from natural climate variability there.

This conclusion should not come as a surprise, considering numerous climate reports from Australian research organizations and a growing body of research in scientific journals showing that as global average surface temperatures climb, the odds of extreme heat are rapidly increasing.

"If anything, these attribution statements are conservative, which is how I prefer them," said Michael Wehner, a senior staff scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, who was not involved in this analysis. "But the researchers have clearly found that the human increase in these measures of heat waves is profound."

A study Wehner published in December along with Daithi Stone and other colleagues tied climate change to deadly heat events in India and Pakistan in 2015. Other studies published in the same month also found links between global warming and heat waves in Australia and China, among other locations.

"The methods that they used to put numbers on the change in likelihood ... is well established and very similar to what we published recently on the deadly 2015 Indian and Pakistani heat waves," Wehner said.

Such post-event scientific sleuthing is known as climate attribution research, and climate experts are aiming to decrease the lag time between a headline-grabbing extreme event occurring, and the time when scientists can say what, if anything, global warming had to do with it.

In this way, it is hoped, people will learn more about how global warming is reshaping the weather extremes they are already experiencing, and provide valuable intelligence to everyone from insurance companies to local governments.