Germantown mom, Ukrainian refugee in Poland forge bond through English-language program

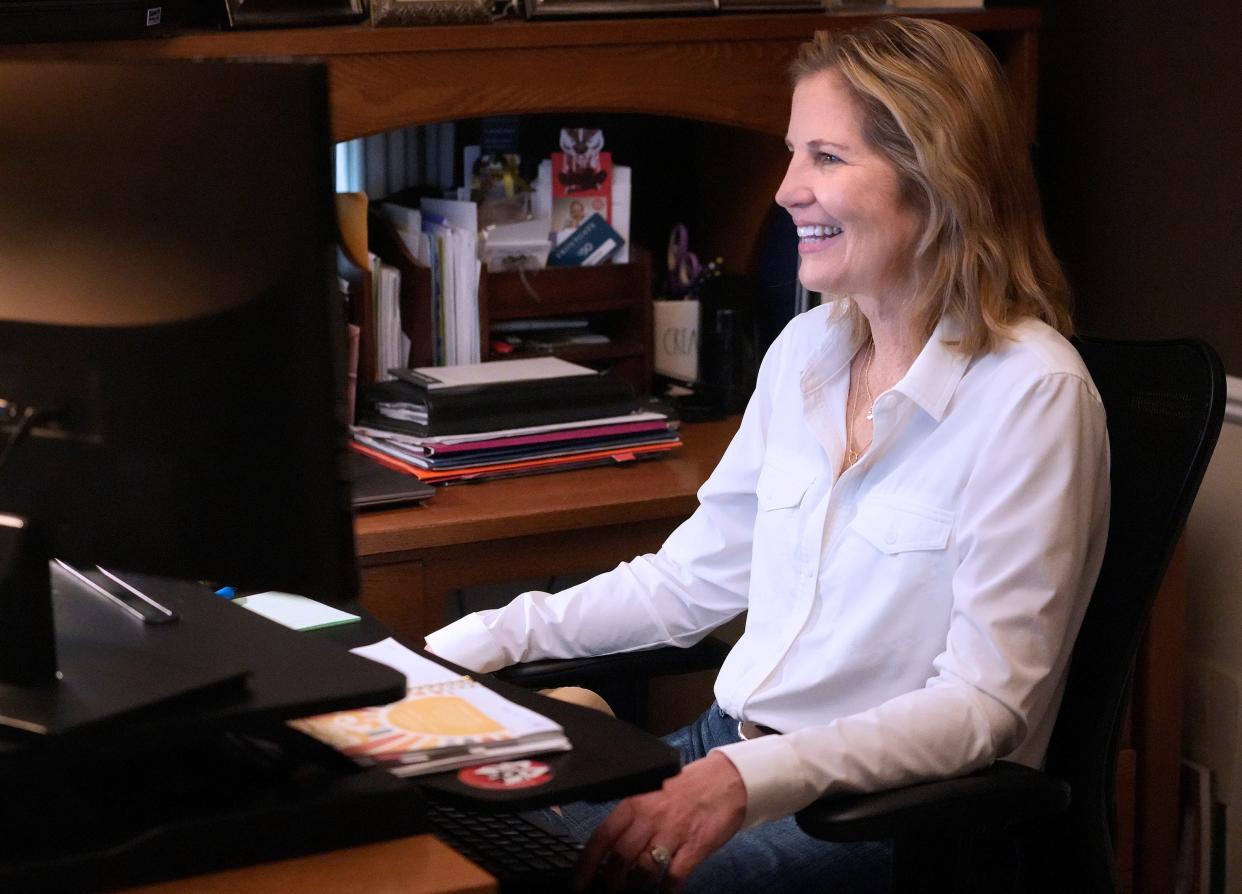

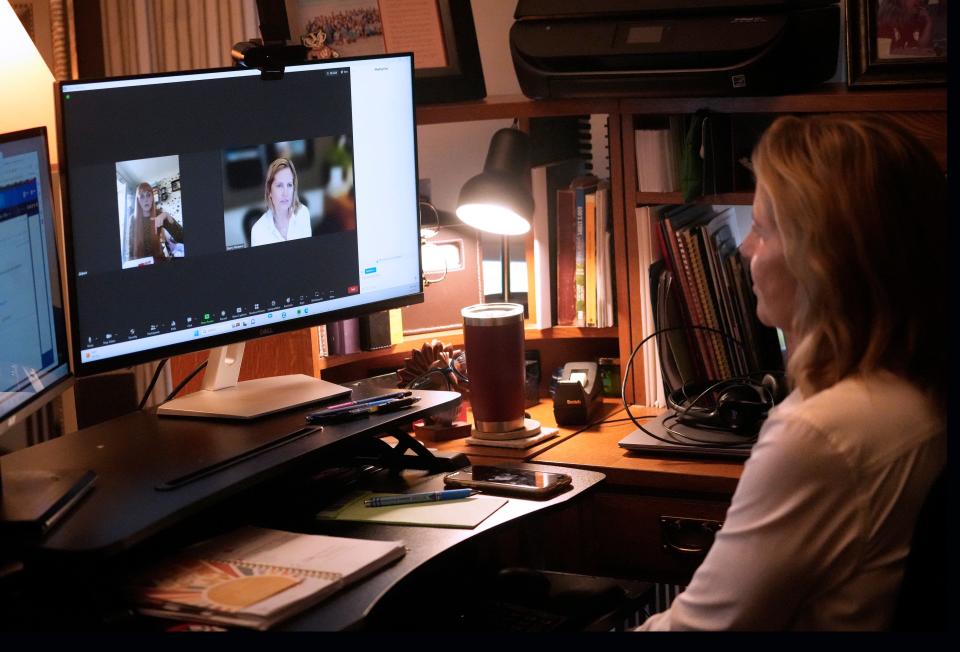

Every Friday morning, Sherry Riesterer of Germantown starts a video call and connects with an unlikely friend across the ocean.

Riesterer has been getting to know Daria Boichenko, a Ukrainian refugee living in the Polish city of Wrocław. There, it’s late afternoon.

It’s part of a program called ENGin that connects English speakers from around the world with young Ukrainians who want to improve their conversational skills in the language. The program’s founder, Katerina Manoff, bills it as a “pen pal program for the 21st century.”

For Riesterer, “it’s five steps better than a pen pal. We actually get to have this one-on-one conversation and see each other,” she said. “We get to experience life together.”

The program has facilitated a friendship between two people who otherwise never would have met.

Boichenko, 32, was building her career at a publishing house when Russia’s war with Ukraine forced her to flee to Poland with her partner. Riesterer, a suburban mom with a background in business, was looking for ways to volunteer, now that her children are grown and out of the house.

“Life is unpredictable,” Boichenko said simply. It’s taught her to say yes to opportunities – like the English program.

More: Ukrainian refugees were quickly welcomed to Wisconsin. Now red tape makes their future uncertain.

For Riesterer, an up-close glimpse into the life of a Ukrainian refugee

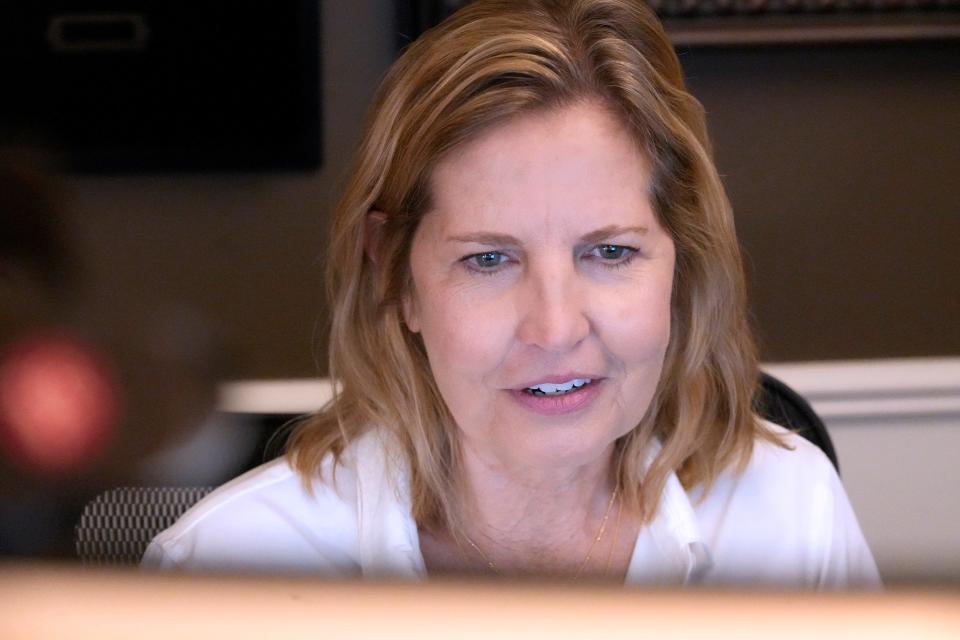

As she searched online for volunteer gigs, ENGin caught Riesterer’s eye. The war in Ukraine was underway, and she wanted to do something to help that wasn’t just donating money.

“I just had a heart for these people,” she said. “This was a perfect way to physically connect with someone.”

At first, Riesterer wasn’t sure she’d be the right fit. She isn’t a teacher and didn't have experience working with English language learners. But the program emphasized it was looking for regular people who had an internet connection and an hour a week.

She signed up.

When Riesterer was paired with Boichenko, she wasn’t sure how much they’d have in common. There was a 20-year age gap.

But it’s been an unexpected joy to learn about Boichenko’s life, family and Ukrainian traditions, she said.

“It’s the first time that I’ve been able to see a little bit more into someone’s real day-to-day life, into their culture a little bit,” Reisterer said.

Through the weekly conversations meant to boost Boichenko’s English speaking fluency, the two have compared Easter traditions, favorite movies and travel destinations.

Together, they watched an episode of Friends – one of Boichenko’s favorite shows – and paused every time there was an American cultural touchstone or expression she didn’t understand.

The war, though, is an unavoidable topic. Boichenko has talked about what it’s like to have family members back in Kharkiv and the challenges of building a life in another country.

“It’s one thing to read about what's happening to people on the other side of the world, and it’s another thing to talk to them about it,” Riesterer said. “It touches your heart more.”

The program is six months long, but Riesterer foresees the two of them continuing to meet online regularly for a long time to come. She’s even been talking about one day visiting Boichenko in Poland or Ukraine.

From December 2022: Milwaukee Ukrainians celebrate the first Orthodox Christmas since Russia's invasion

From March 2022: Medical students in Ukraine flee the country after their school was bombed by Russian rockets and a classmate killed

English skills will help Boichenko adjust to life in Poland

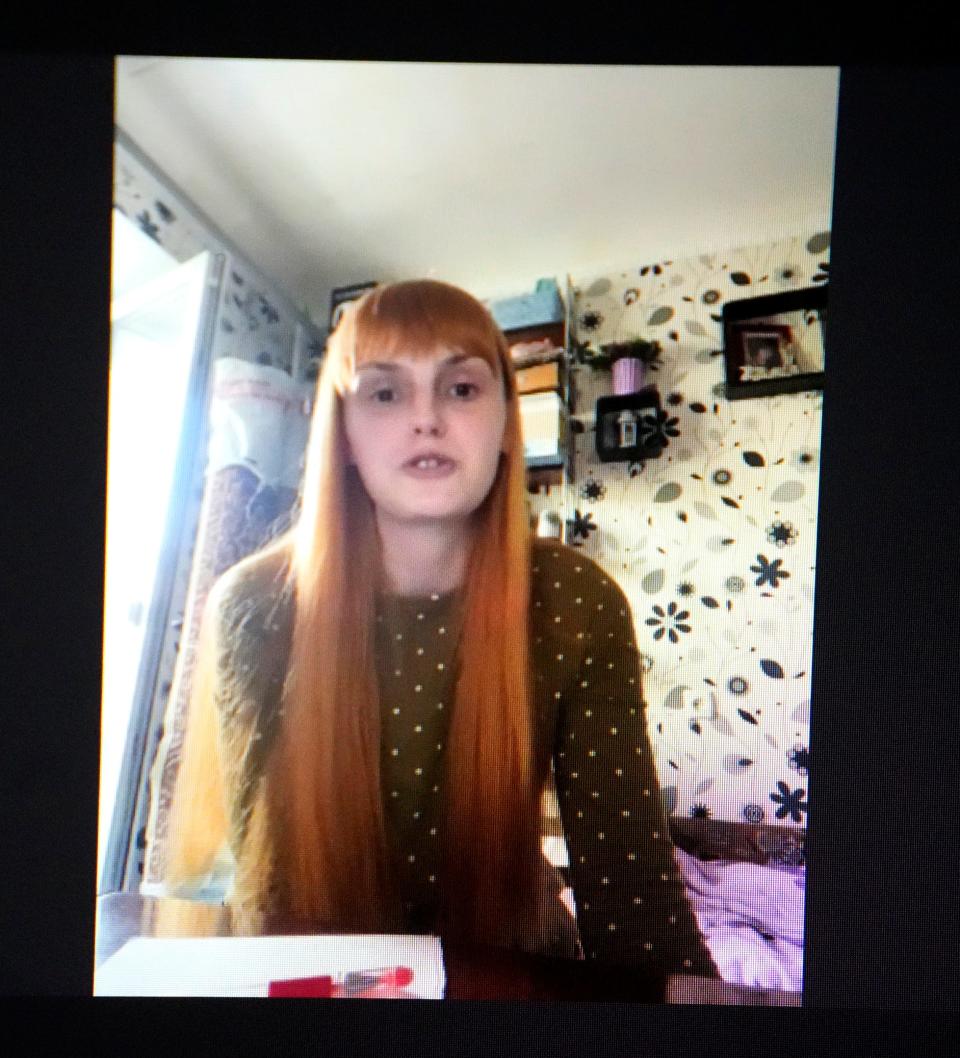

For Boichenko, the weekly calls offer a point of connection in a time of upheaval.

She never expected to have to leave Ukraine, and didn’t speak Polish when she resettled in Wrocław, the country’s fourth-largest city.

Although she’s now started to learn Polish, she’s been using English to speak with shop keepers and other Poles as she’s set up her new life – buying a SIM card for her phone, and purchasing car insurance.

Boichenko learned English in school but needed a refresher to be able to operate more smoothly day-to-day.

It was especially important to improve her language skills because colleagues at her new job – a Polish publishing house that makes textbooks and educational materials – communicate in English.

“I want to communicate easier and understand more,” Boichenko said. “I want to feel more free.”

Boichenko’s new life in Poland can feel narrow at times. She works from home and in the evenings she takes walks or goes grocery shopping. On weekends, she goes to museums and strolls through the city’s downtown area. Her partner is a truck driver so he's away a lot of the time.

Sometimes, she visits her sister, who lives an hour away. But she doesn’t have any Polish friends yet. Learning English might help her expand her social circles and adapt to life there, she said.

“After the beginning of the war, I understood that I am my main resource,” Boichenko said.

Speaking English well could open doors for her in the future, she realized – not just in Poland, but anywhere she might go next in the world.

Founder hopes program will help Ukraine grow, rebuild

ENGin’s founder, Manoff, hopes the program serves as an “engine fueling Ukraine’s growth.”

Manoff, who is based in the Washington, D.C. area, sees strong English-language skills as the key to Ukraine’s future success.

Ukraine is one of the lowest-ranked European countries in English proficiency, according to an annual global survey from EF Education First. Manoff knows that highly developed countries also record high English fluency.

“I like to sometimes say I’m trying to turn Ukraine into Norway,” she said — that is, a country that's thriving economically that also ranks near the top of the world in English skills.

Manoff launched the program in 2020, just before the pandemic hit, and it’s since grown to nearly 30,000 participants in the last three years, she said.

The connections forged across the ocean offered Ukrainian young people and their English-speaking conversation partners a reprieve from the loneliness and isolation of the pandemic, Manoff said. Those bonds have only proven more valuable since the war broke out.

The conversations, and taking steps toward English proficiency, help Ukrainian participants feel “like an agent of their own destiny rather than a victim,” Manoff said.

“Language is power, and having the power to tell their stories to the world is a huge part of it,” she said.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Germantown mom, Ukrainian refugee form bond over English language