German court ruling is key moment in debt crisis

FRANKFURT, Germany (AP) — A closely watched ruling by Germany's Federal Constitutional Court could trip up European leaders' efforts to calm the region's debt crisis.

The court — akin to the Supreme Court in the U.S. — will decide Wednesday whether or not it will allow Germany to join the European Stability Mechanism — a new, permanent €500 billion ($639 billion) bailout fund for the 17 countries that use the euro currency.

Since July, the court has been considering a series of challenges to the ESM and a parallel treaty requiring governments to limit the amount of debt they pile up. The challenges have been made by a number of different groups, all concerned that the measures limit Germany's constitutional powers.

Markets — not just in Germany but globally— are keeping a close eye on the ruling.

Here are some of the key issues:

Q: What is the European Stability Mechanism?

A: It's a fund backed by the 17 countries that use the euro, through €80 billion to be paid up front and €620 billion in promises to pay if needed. Its purpose is to support countries that have gotten into financial trouble and can't borrow normally.

The €700 billion in pledges and capital would enable the funds to raise and lend €500 billion by selling highly rated bonds on the open market. It takes over from an earlier bailout fund, the European Financial Stability Facility, which has handled earlier bailouts of Greece, Ireland and Portugal.

First and foremost, the ESM can loan money to a country if all the member countries agree it deserves the help. The loans would help that country keep up its bond repayments.

The ESM can also buy countries' bonds at auction or offer a standby loan that would be drawn only if a country needs it.

Simply having the ESM around could help calm markets even if it is not used. It was meant to be in place by July but can't open for business without Germany, the eurozone's largest member responsible for 27 percent of the fund's financing.

Q: Who is against it and why?

A: The people who brought the court case say joining ESM hands over the German parliament's power to decide how taxpayers' money is spent. They fear it could mean an open-ended burden.

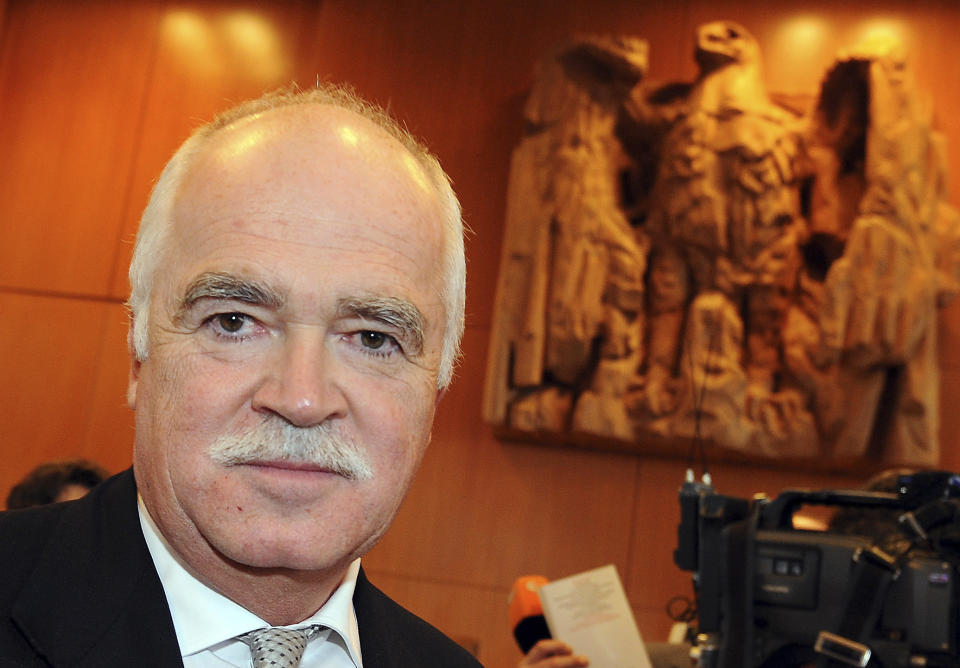

Opponents include conservative legislator Peter Gauweiler, who has brought previous such suits, and a group of professors. Joining him are a group calling itself "Europe Needs More Democracy", which says 37,000 people have signed up to its complaint, and is Germany's Left Party, which says ESM bailouts will only enrich the financial industry.

Q: What exactly is the court ruling on?

A: Technically speaking, the court will only decide whether to issue a temporary order that will prevent President Joachim Gauck from signing the ESM ratification into law. That order would last until the court can make a final decision on the full case in a few months, probably early next year.

Legal experts say the decision Wednesday will likely give some clear signals about how the court will eventually decide.

Q: What is the court likely to do?

A: The German parliament has already ratified the treaty creating the ESM but Gauck has held off signing the agreement until the court decision.

Experts say the court will likely let Gauck sign and signal that it will approve ESM. But it might also demand additional steps by the German government to guarantee that parliament has enough of a say in what the ESM does.

If the court says it's OK for Gauck to sign, the ESM could be up and running in early October, officials say.

However, a surprise can't be ruled out. The court could conceivably issue an order blocking Gauck from signing — and indicate that its eventual decision will find that ESM membership goes too far in infringing Germany's constitution.

If that's the case, Germany might eventually need a referendum on a new constitution to join ESM or need to take more steps linking it to the EU. That could take a year or two.

Q: What happens if the court blocks Germany joining the ESM?

A: Because the fund can't go ahead without Germany on board, Europe would be without a solid backstop to support troubled governments. It still has a temporary bailout fund, the European Financial Stability Facility. But that €440 billion fund has only €150 billion or so left after bailouts for Greece, Ireland and Portugal. Many analysts expect Spain to ask for a bailout.

More than that, the ESM is a key part of plans by the European Central Bank to buy government bonds of struggling countries on the open market. The ECB has said it can do that, but only if the countries first ask the EFSF or the ESM for help and if the bailout fund joins in buying bonds. The ECB could on paper start bond purchases with only the EFSF in place, but the limited resources available to the EFSF would raise questions about the overall strength of any new rescue effort.

"If the judges were to strike it down, it'll surely lead to mayhem in the market until we get the results of a likely German referendum on Europe sometime early in 2013," UniCredit's chief global economist Erik F. Nielsen wrote in a note to investors.