German company makes biodegradable fruit and vegetable net packaging

Step into a supermarket and you will likely see plenty of plastic net packaging, conveniently bagging together onions, oranges, limes or lemons.

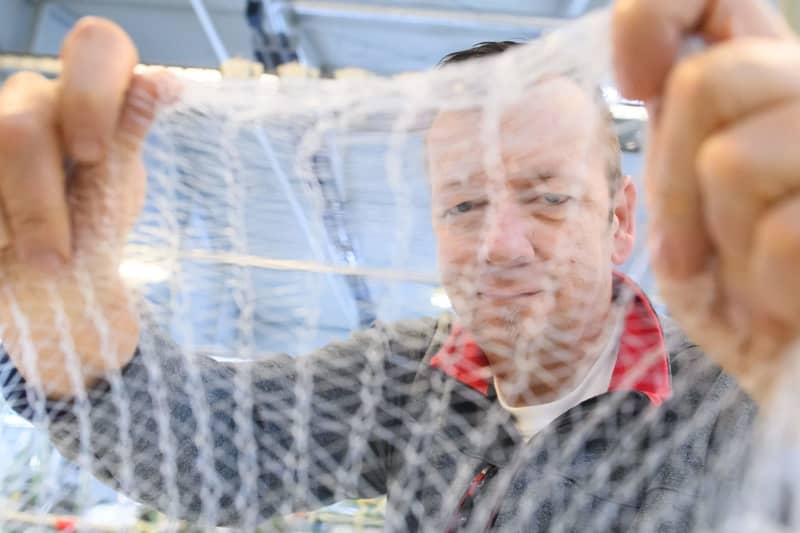

That might not be ideal for the environment but it is good business for Thomas Hartung, managing director of Mesh Pack in the town of Kusey in Germany.

Mesh Pack produces all types of packaging nets from plastic granulate but it is also focusing increasingly on sustainable alternatives. A new net based on corn starch has won several awards.

Other makers of the plastic knitted packaging are also creating more environmentally friendly versions, with some using cotton or cellulose to make the bags.

In addition to customers in Germany, Mesh-Pack also supplies the netting to around 20 European countries, Hartung says. On top of that come exports to the US, South Africa and Australia, and this year to New Zealand.

Alongside making net bags for fruit and vegetables, the company also makes netting for Christmas trees, protective nets against pests and agricultural nets for silos or to keep bales of hay in shape.

All that means 600 to 700 tonnes of the goods are sent out from its factory annually.

Company boss Hartung is well aware of the environmental problems the nets create. "We produce just as much waste with them. The nets are intended for single use. So far, the only disposal option has been the residual waste bin."

That is something environmental activists want to avoid. "From our point of view, it is important that unnecessary packaging and products are avoided as a priority. Reusable systems are essential for this," says Jasmin Boße from the Plastics and Packaging department at the Federal Environment Agency in Dessau-Roßlau, Germany.

If packaging is necessary, then it is important to try and reuse the material as much as possible, while assessing other factors such as material consumption and recyclability.

Hartung is also driven by the idea of sustainability. By working with the Fraunhofer Institute in Halle, Germany, his company developed a new type of bionet and presented it at trade fairs for the first time in 2022.

The advantage of this first available "ribbon net" made from corn starch is that it is quickly and completely biodegradable. Plus, in terms of quality, it is in no way inferior to that of conventional nets.

The raw material for the net literally grows on the doorstep. Similar products are based on cellulose or sugar cane.

In Germany, the landscape for alternative forms of net packaging is gradually growing greener. In the Münsterland region, Naturnetz has been knitting nets for fruit and Christmas trees, using yarns made from cellulose based on beech wood.

They are produced in Austria, Naturnetz Managing Director Sylvia Segeler says. "The nets usually decompose within 12 weeks."

She said the challenge was to produce nets stable enough to hold together trees, which are compressed to a diameter of around 25 centimetres.

All year long, there is demand for fruit and vegetable nets from direct marketers and farm shops, she says. "They are slightly more expensive because it's a different product."

Segelerv did not provide exact figures but says she expects plastic to largely disappear from small packaging in the future. She says in this area, France is leading the way.

But the companies are winning prizes for their work and Hartung feels vindicated. He is still working on a truly sustainable product, because in his view, what he is making right now does not go far enough.

"In our view, biodegradable plastics offer no ecological advantages, as composting mainly produces CO2 and water and removes valuable materials from the cycle," says Boße. "At best, bio-based plastics with the same properties as recyclable plastics should be used to keep valuable resources in the cycle."

Mesh Pack is working with scientists at the Fraunhofer institute to develop more innovative products.

Hartung took over the company together with his brother Michael in September 2020. Both were already established in the town with a building technology company their father had taken over.

Hartung came to his business almost by accident. When its previous owner announced that he was pulling out of Mesh Pack and shutting down production, they stepped in to save the site. Looking back, it was a pretty impulsive decision, "more out of a beer mood," says Hartung.

Founded in 1997, the company now has 42 employees again, who produce nets in shifts. Might the new, more expensive product succeed? That remains to be seen. So far, it makes up 3% to 5% of turnover.

Hartung is confident, but says, "Ultimately, it's the consumer who will decide."