French small business faces job-creation hurdles

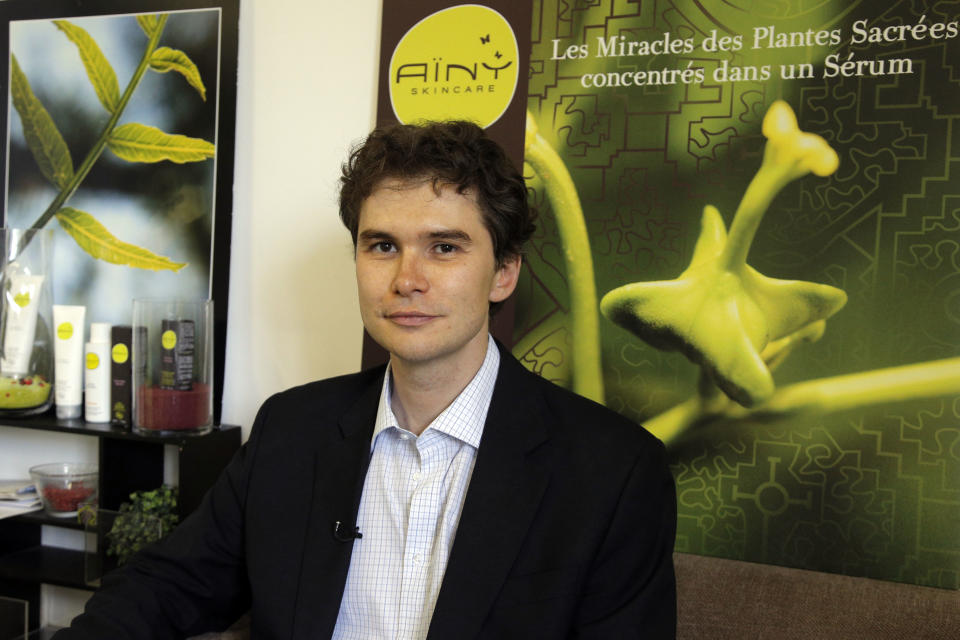

PARIS (AP) — Europe needs jobs, and French entrepreneur Daniel Joutard wants to create them, hiring more employees for his skin-care products company. Yet he can't take the risk — in large part because of France's inflexible workplace protections.

The 37-year-old is among thousands of small- and medium-size business owners who will be crucial to helping France — like other countries in Europe — reduce a double-digit jobless rate, and ultimately shrink its hefty state budget deficit by bringing in more tax revenues.

Small- and medium-size companies made up over 99 percent of enterprises both in France and the EU more broadly, providing for about two-thirds of all employment, according to a study published in January for the European Commission. Crucially, across the bloc, these companies created about 85 percent of net new jobs from 2002 to 2010. France alone counts more than 3.4 million small- to medium-sized companies, defined as having up to 250 employees.

But businesses like Joutard's 3-year-old venture, Ainy, say it's costly and complex to hire when times are good, and costly and complex to lay employees off when times are tough. And so they're staying small, and not taking on any workers at all.

THE HIRING HAZARD

Ainy's New-Age creams, hydration treatments and lip balms have gotten solid press reviews. Top-tier retailers have offered up prime shelf space. A former R&D chief at Chanel has joined up — lured in part by the fair trade ethos of the trans-Atlantic startup and curiosity about the plants it uses. Ainy also eschews patents, insisting that it is unfair to trademark the expertise and knowledge of the indigenous South American peoples that the company collaborates with.

It's a formula that has struck a chord with the French public — and business is good, with revenues doubling in 2011.

Joutard now has six employees, and half of his revenues come from outsourcing research for customers. In his lab, a white-smocked chemist blends creams containing extracts from exotic Andean plants like Sacha Inchi, whose seeds have anti-aging properties and high concentrations of Omega-3 and Omega-6.

"We could hire two or three more workers," Joutard said, but adds: "Hiring becomes a risk — because once you have hired someone, if the business is not there, it's complicated to keep that person busy."

And even more complicated to let that person go.

"So we'll only hire someone when we're 100 percent sure."

In France, which takes pride in its revolutionary past, labor reform is a tall order: Strikes are common and workers even occasionally take their bosses hostage — in "bossnappings" — as a form of protest. The last big government effort to make it easier to hire and fire in 2006, during President Jacques Chirac's tenure, resulted in weeks of protests that shut down universities nationwide — and was eventually scrapped.

French governments for years enshrined workplace protections to ensure job security, limit worker exploitation and abuse, and protect the French way of life. That fabled lifestyle includes generous holiday packages, state-sponsored healthcare, and — since the late 1990s — the controversial 35-hour work week.

These days, entrepreneurs like Joutard say the laws should adapt to the times.

"What I want is greater flexibility, to be able to hire. But for that we must be sure that if the economic situation changes, we can let somebody go in a simple way, without any drama," he said. "In return, employees must be able to keep their employability, and get trained during these times."

Under French law, employers must pay at least some severance — at the very least, one-fifth of their monthly salaries per number of years employed, though it can go much higher depending on labor accords. Then there's the risk that a fired employee will seek redress in one of France's labor courts — something that Joutard has experienced firsthand.

"In general when you hire someone in France, it's impossible to get rid of them, or at least only at a prohibitive cost," said Francois Derrien, a professor of finance at the HEC business school southwest of Paris. "In sum, when you hire someone in France, it's for life."

HOLLANDE'S PLAN

In recent weeks, France's new President Francois Hollande has sought to show his Socialist-led government is working to reduce France's 10-percent jobless rate and rein in state spending. He made often-combative labor and employers' unions sit down together last week, ordering them to devise reforms to underpin new legislation to be passed by year-end. He's also commissioned a report — to be published next month — on ways of making French business more competitive.

Lurking behind Hollande's push is concern that France could slide into a crisis like the ones faced by other European Union partners, including Greece, Italy, Ireland and Spain.

The French economy, Europe's second-largest after Germany, is in a rut. In an analysis in May, BNP Paribas economist Helene Baudchon noted that France's growth rate averaged 1 percent a year from 2001 to 2011 — a full percentage point less than in the previous decade, and down from the long-term average of 3.3 percent since 1950.

One of Hollande's top job-creation ideas is a "generations contract" to encourage older workers to pass on knowhow to younger hires, and adding 60,000 jobs in the public education sector over five years. He also wants to create a state-backed investment bank to help firms start up and grow.

Last month, Hollande unveiled a plan for the government to pay most of the salaries of tens of thousands of young people hired next year — part of his war on unemployment. Under the idea, companies that hire a person aged between 16 and 25 for at least a year will pay as little as 25 percent of the salary, in the plan to create 100,000 "contracts for the future" in 2013.

More recently, he suggested another solution to encourage job creation: shifting some of what companies pay in labor fees to households. In other words, income taxes might go up so that often-onerous payroll taxes could come down.

Yet while Hollande acknowledges that employers need more flexibility, he also says any reforms should include greater job security for workers.

"It's an accord that must be win-win, give-and-take," Hollande told TF1 TV. "If this historical accord can be worked out, it will be very important for our country."

Some economists say "win-win" is simply an impossible task — and something has to give.

THE STATE: A HELP, AND A HINDRANCE

Complicating the picture for Joutard is the fact that the helping hand of the ever-present state in France can be spotted even among start-ups — especially those that prove they are true innovators.

"We are less competitive because of payroll taxes, for example, which are very burdensome ... which is another factor that limits our hiring," said Joutard. "On the other hand, because we're an innovator, we get more help (from the state) than others."

In his small, state-subsidized office and research lab in Paris, Joutard says he would never think of uprooting from France and going to where labor laws are more flexible. He says he owes the country a lot: He received a top-flight business-school degree here, and has received zero-interest loans and cut-rate rent from the Paris regional government, which has rewarded his entrepreneurial drive.

But he also groans that roughly 45 percent of the gross salaries he pays are swallowed up by payroll taxes. French paychecks often come with a long list of such taxes — including fees for healthcare, pensions, unemployment insurance, disability insurance, worker training and fees for a fund aiding the elderly or the disabled.

LOW MARKS ON LABOR FLEXIBILITY

The World Economic Forum, in its Global Competitiveness Report published this month, ranked France 141 out of 144 countries in terms of "hiring and firing practices."

Overall, France fell three spots from last year to 21st in the WEF's Global Competitiveness Index ranking. It generally fared well on gauges of infrastructure, health and education, and was 10th in innovation.

Therein lies the rub: innovators like Ainy want to grow, and they do get help from the state to get going. But regulatory hurdles abound when those same companies want to grow and compete.

French labor law had its origins in a laudable idea, Joutard said: To protect workers from exploitative employers like those from the industrial era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

"But the world has changed, and is now much less predictable. So these protections become a brake," said Joutard. "A big company can handle these difficulties, it's harder for a small one."

___

Jamey Keaten can be reached at twitter.com/jameykeaten