French court rejects plea from luxury wine label to stop cheap blends being sold under 'Petrus' name

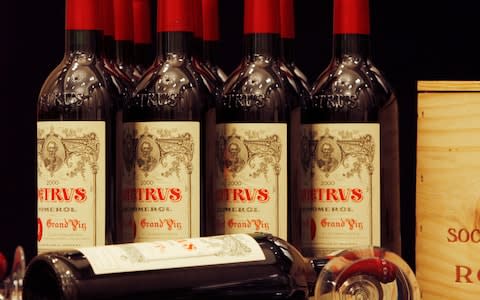

It is the ultimate status symbol for wine buffs and commands astronomical prices, but Petrus risks losing its cachet after a French court rejected its plea to retain exclusive rights to the hallowed name.

After a seven-year legal battle, the Bordeaux appeals court has ruled that the makers of a cheap, blended wine that sells for less than £10 a bottle can continue to use the name ‘Petrus'.

The court quashed a petition by Château Petrus, which produces the original Petrus, to force the makers of the humbler Petrus Lambertini to drop the word ‘Petrus’ from their brand name on the grounds that it was misleading.

Petrus, known as the “Rolls-Royce” of clarets and favoured by oligarchs and City high-fliers, is produced in Pomerol, the smallest and arguably the most prestigious of Bordeaux’s wine-growing regions.

A magnum of its 2015 vintage costs more than £5,000, and the average price of a bottle of Petrus exceeds £1,800. Unlike many other “grands vins” of Bordeaux, which also produce cheaper “second wines”, Petrus makes only one high-quality vintage.

By contrast, Petrus Lambertini is an unassuming table wine made from grapes grown in different vineyards near Bordeaux.

The name “Petrus Lambertini Major Burdegalensis 1208”, registered as a trademark by the manufacturer, refers to Bordeaux’s first mayor, who in 1208 refused to hand the keys of the city to the besieging forces of the King of Castile, in modern-day Spain.

The dispute began in 2011, when Petrus Lambertini was first marketed. Its labels showed “Petrus Lambertini” in large letters, with “Nº 2” underneath. Château Petrus argued that was misleading because consumers would think it was Petrus’s “second wine”, meaning a batch not quite good enough to be selected for the premium vintage.

Château Petrus accused CGM, the producer of Petrus Lambertini, of “unfair and misleading commercial practices” after seeing an online advertisement for “Petrus second wine”, posted by a private individual who was in fact selling Petrus Lambertini.

Initially, a court upheld Château Petrus’s argument that there was a risk that consumers would confuse the two wines.

It fined CGM and ordered it to halt sales under the brand name.

But the firm appealed and another court has now accepted that the two labels are “radically different”. It ruled that consumers could not fail to realise that Petrus Lambertini “is neither a Petrus nor a second Petrus wine, which does not exist.”

The court judgment complimented CGM on “their clever use of the trade mark which they registered in order to attract the customer’s attention,” pointing out that the practice was not illegal.

The new ruling allows the firm to resume sales without removing ‘Petrus’ from its brand name.

Stéphane Coureau, CGM’s director, welcomed the decision, saying Petrus Lambertini would soon be back on the shelves.

“With 47 differences between the labels of Petrus and Petrus Lambertini, that is enough to avoid any confusion,” Mr Coureau said. “There are an enormous number of similar names used in the wine industry today, but the real problem is differentiation, to ensure that no producers’ rights are infringed.”

Elisabeth Jaubert, a spokeswoman for Château Petrus, said the company would launch a counter-appeal to a higher court. “The Court of Cassation will now assess the legality of the decision by the appeals court,” she told the Sunday Telegraph.

Jean-Baptiste Thial de Bordenave, a lawyer specialising in intellectual property, said he was surprised by the ruling.

“I don’t understand how a professional winemaker can register and use one of the world’s best known brands in good faith,” he said.