How a French Atheist and an American Abolitionist Ended Up Creating a Christmas Classic

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Origin stories were kind of a thing this year. So was the anti-origin story movement, or rather, the conservative campaign to cancel any lessons about history dealing with slavery or decentering whiteness. Between the two, it seems like a perfect moment to examine the origins of one of the Christmas songs that becomes ubiquitous at this time of year, the soundtrack to a million Omicron superspreader shopping expeditions.

For example, did you know the guy who wrote 1857’s “Jingle Bells,” James Pierpont, despite being from a well-known family of Boston-based Unitarian abolitionists, grew up to become an ardent secessionist and Confederate soldier—and that the first live performance of “Jingle Bells” may have been by a white performer in blackface? (Also, Pierpont’s nephew was J.P. Morgan, so he’s also kinda-sorta to blame for your checking late fees.) Contrast that guy with Ohio’s Benjamin Hanby, also the offspring of abolitionists, who was active alongside his family in the Underground Railroad, and who penned “Up on the Housetop” in 1864.

‘Silent Night’ at 200: The Secret History of the Greatest Christmas Carol Ever

And then there’s “O Holy Night.” What is now regarded as a Christmas standard features lyrics originally penned by an atheist French winemaker, music composed by a Jewish Frenchman, and words translated into English by an American abolitionist. It was banned for a period in France before becoming an anti-slavery anthem in the U.S. during the 1850s.

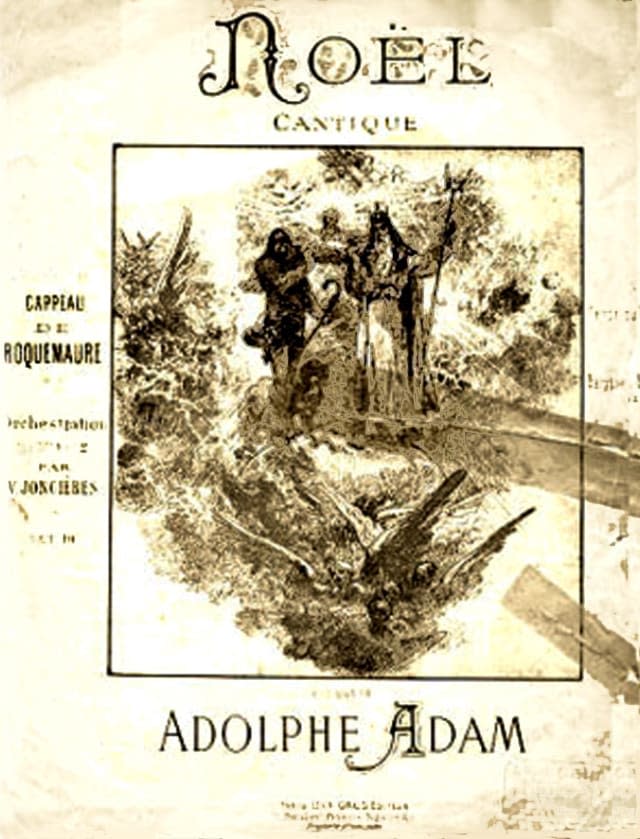

Things start in 1843 or 1847—there’s some discrepancy about the year—in Roquemaure, a small town in the Rhône valley region. Placide Cappeau, who had followed his father into the wine business, was also known for the poetry he composed. Though a critic of the Catholic church, Cappeau was asked by the local priest to write a few stanzas in celebration of the town cathedral’s newly refurbished organ. He is said to have written the song’s words while in transit to Paris on business, with the biblical Gospel of Luke as inspiration. On the advice of the same clergyman who had commissioned him, Cappeau took his completed work—then titled “Minuit, Chrétiens,” or “Midnight, Christians”—to Adolphe Adams, a composer of some renown. Adams, who was of French-Jewish descent, arranged the music, and the song was newly christened as "Cantique de Noel.” The carol would make its world debut, with opera singer Emily Laurey belting lyrics, during Christmas eve midnight mass at the Roquemaure church.

Though "Cantique de Noel” would quickly become a French Christmas favorite, it was later denounced by the French Catholic church—a reported consequence of Cappeau being an avowed atheist and socialist, along with the discovery that Adams was Jewish, not Christian. One bishop reportedly dismissed the song as having a "lack of musical taste and total absence of the spirit of religion.” There was also some resistance to Cappeau’s overtly anti-slavery lyrics in the third verse, which were perhaps made more glaring by his emergent political outspokenness. In any case, the ban reveals where the French Catholic church stood on matters of abolition.

It’s worth recalling here that in this era, France was still stealing Black folks from Africa as part of the transatlantic slave trade, though it would definitively abolish the practice in 1848. By then, an estimated 1.4 million human beings had been seized, taken to those places colonized by France— including but certainly not limited to Guadeloupe, Martinique, and above all Saint-Domingue, aka Haiti—and enslaved under brutally cruel, and frequently lethal, conditions. In fact, France is the only country that ended slavery, in 1794, due to its loss against Black Haitian fighters, only to reinstate it in 1802, courtesy of Napoleon. So much for liberté, égalité, fraternité.

In any case, "Cantique de Noel” would make its way across the Atlantic to John Sullivan Dwight, a white American abolitionist, Unitarian minister, musician and classical music aficionado who published a magazine called Dwight's Journal of Music.

John Sullivan Dwight

In 1855, Dwight translated Cappeau’s lyrics, giving special care to the third verse. A fairly direct translation from the French is below:

The Redeemer has overcome every obstacle:

The Earth is free, and Heaven is open.

He sees a brother where there was only a slave,

Love unites those that iron had chained.

Who will tell Him of our gratitude,

For all of us

He is born,

He suffers and dies.

These words, Dwight converted thusly, to keep the poetics in place while retaining the original meaning:

Truly He taught us to love one another;

His law is love and His gospel is peace.

Chains shall He break for the slave is our brother;

And in His name all oppression shall cease.

Sweet hymns of joy in grateful chorus raise we,

Let all within us praise His holy name.

Dwight gave his translated verse the title “O Holy Night” when he published it in his music periodical in 1855. It apparently became a hit in the U.S., gaining popularity among the abolitionist crowd during the Civil War. Even as the song was being banned in its home country, it was becoming a staple of Christmas, and a song of protest, thousands of miles away, in the U.S. It’s long since become part of the broader American Christmas songbook.

It also was part of radio history. On Christmas Eve 1906, Reginald Fessenden, an inventor who had worked with Thomas Edison, is said to have played “O Holy Night” during the first radio broadcast involving music and voice.

There’s also a story, sometimes told about the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 and sometimes about the Great War, about German and French troops leaving their trenches to sing “O Holy Night” together in an impromptu Christmas ceasefire. That’s almost certainly apocryphal, but it was definitely a pretty groundbreaking song for its time, from start to end.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.