Fosse put on Broadway's most rigorous dance show. Can a new generation stage it safely?

When Bob Fosse's "Dancin'" opened on Broadway in 1978, it began with a warning: This show is not a traditional stage musical, with characters who fall in love, conquer villains or leave orphanages.

Its 16 principal performers — originally including Wayne Cilento, who later choreographed "The Who's Tommy" and "Wicked" — then launched into a marathon of rigorous musical numbers, showcasing a notably wide range of dance and music styles.

"It was very physically challenging and the dancing was really intense," recalls Cilento, who was 29 at the time and nabbed his first Tony nomination for the role. "It was definitely the worst thing I've ever done, but also the most rewarding."

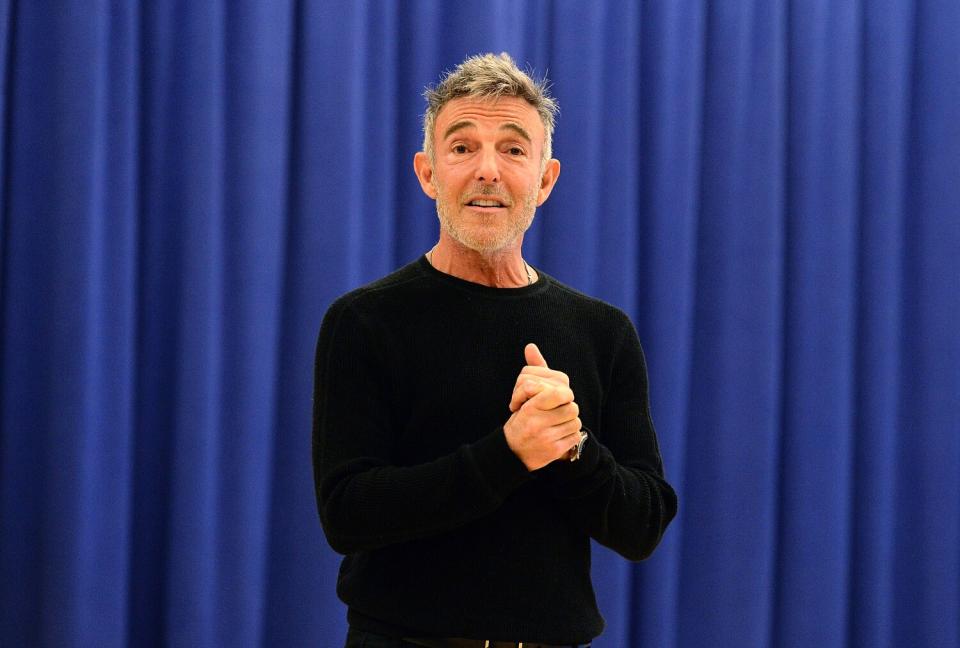

"Dancin'" played for four years and brought Fosse his seventh Tony Award for his choreography. But it has rarely ever since been revived — on Broadway or elsewhere — partly due to its dangerous degree of difficulty. That is, until now: A Broadway-bound revival of the revue is playing at San Diego's Old Globe through May 29, with Cilento himself at the helm.

"It's an entertaining musical that's a celebration of life, of dance and of dancers," says Nicole Fosse, who has been pushing a revival of her father's passion project since 2005. "I wanted to make sure that the right director would stay true to all of the intentions of the original show and everything that Bob Fosse was always about."

Bringing back "Dancin'" raises the question of whether such a physically ambitious show can be restaged safely. "There's enough dancing in it for four regular musicals; it's like playing a pro football game eight times a week," Fosse told The Times in 1982. "No matter how carefully I warn the dancers to warm up, a lot of injuries happen — particularly as the run wears on."

The original "Dancin'" employed up to six understudies, each of whom needed to rehearse for a month before executing the dozens of jazz, ballet, tap and contemporary dance routines. Between sprained ankles, sore knees and requests for time to rest, some shows went on with as many as seven people missing; others had actors performing what they could through the pain.

"People would call in and say, 'I'll do my three spots and sing that, but I can't be in the big production numbers,' and stage management would say, 'Come do what you can do and then we'll put the swings in with the stuff that you can't do," says Cilento. "Sometimes I was pissed because I couldn't do that, since I was in almost every number. I was like a racehorse, running around crazy."

Now 72, Cilento has made changes to "Dancin'" to help ensure the revue is both entertaining for 21st century audiences and sustainable for a new generation of performers. Presented amid projection set designs and industrial scaffolding — the latter as an "All That Jazz" reference to salute Fosse's film career — the production has been trimmed from three acts to two (now rid of historically controversial sequences like "Dream Barre" and "Joint Endeavors").

No single performer is assigned the same volume of routines Cilento once had. "We evenly distributed the show so there's less injuries," he says. "Also, I wanted every dancer to have spots in the show that they're recognizable and featured to their best ability. We're really putting them in a situation where they'll be able to shine."

Still, the new "Dancin'" — which includes a ballet that pulls moves from Fosse's short-lived musical "Big Deal" — is still a behemoth for the dancers onstage, cast from among 700 hopefuls and doing double shows up to three days a week.

"All of us are onstage basically the whole time, and you don't stop until the show stops," says performer Karli Dinardo, 28. "Your 30-second quick change is just as choreographed as anything onstage. Even intermission is timed out within an inch of its life."

The production provides physical therapists and massage therapists for the cast of 16, plus the four understudies — all of whom fill their time off with strength regimens and regenerative activities like high-intensity workouts, acupuncture, meditation and salt baths.

"We're all sore and tired and excited," says performer Manuel Herrera, 38. "But we understand that this is a huge undertaking, and that this choreography takes technique and stamina to do it well, from beginning to end. So you have to do the outside work of taking care of yourself in order to be able to do your job and be in this show."

Yet the most helpful resource has been Cilento himself. Dinardo and Herrera tell The Times that the revival's director-choreographer has been generous with the "nuggets of wisdom" he received from Fosse firsthand, and brings an empathy from experiencing himself the physical and mental toll "Dancin'" can have on its performers.

It's a foundational part of Cilento's approach to the production. "I constantly check in with them, sit them down and tell them they're enough," he says of his cast. "I don't want them to feel like every hand gesture has to be this way or that way, I don't want to strip them of their individuality."

"I taught them the combination, and I gave them the freedom to bring themselves to his work," he continues. "I want them to perform Bob's choreography but to do it the way they would do it. I think that then brings his work up to another level."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.