'Fort Collins didn't begin with Fort Collins': Northern Colorado's Native American history

Editor's note: This story is a companion to the latest episode of "The Way it Was," the Coloradoan's history podcast. To hear about Arapaho history in Fort Collins, tune into the podcast for more from Hubert Friday, the great-grandson of Arapaho Chief William Friday, and Northern Arapaho tribal member Yufna Soldier Wolf.

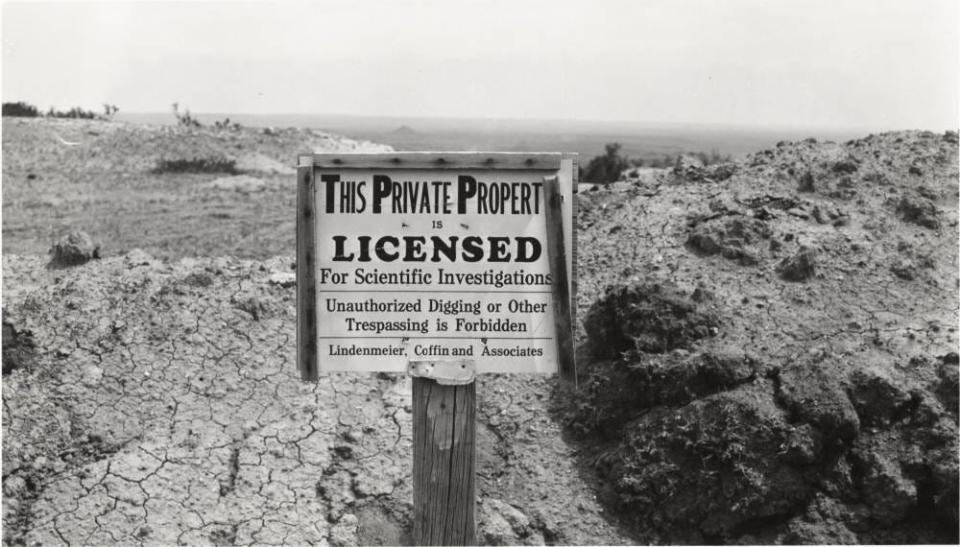

Nearly a century ago, thousands-year-old spear points were pulled from the earth on a ranch north of Fort Collins.

The discovery turned out to be groundbreaking — literally and figuratively — for Northern Colorado, as the Smithsonian Institution later excavated the site and turned up more signs of life dating back more than 12,000 years.

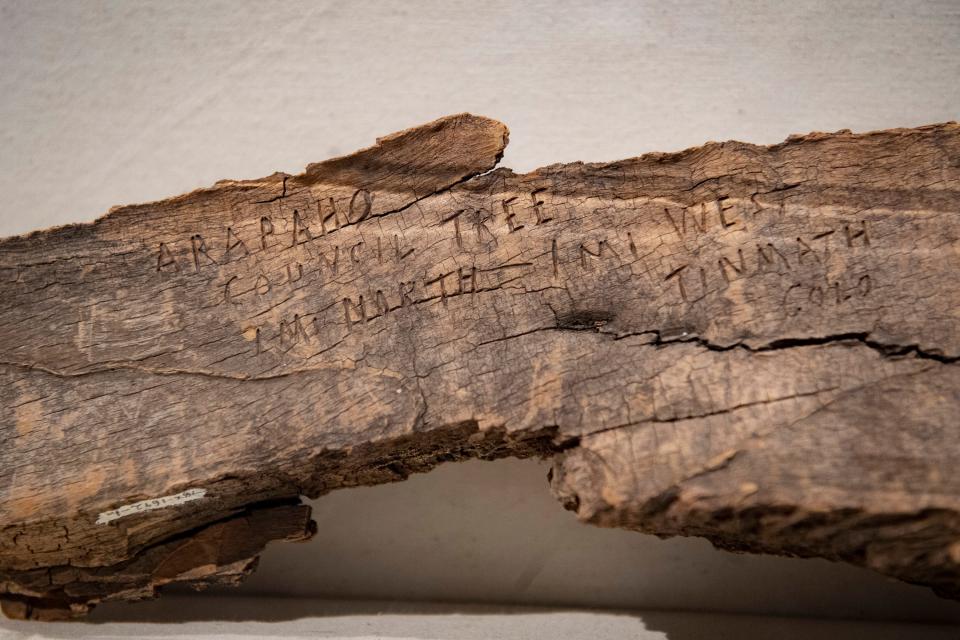

From the Ice Age-old spear points to an early-19th century Native American and fur trapper campsite found among the crimson rocks of Wellington's Red Mountain Open space, to a gnarled Arapaho "council" tree that stood along the banks of the Poudre River into the 1950s, signs of Indigenous cultures and life have lingered in Northern Colorado.

A Coloradoan investigation: Forest Service was supposed to protect the water sources of the American West

They tell a story of the area that begins long before Civil War soldiers ventured down to the banks of the Cache la Poudre River to establish the military outpost that would eventually become Fort Collins.

"Fort Collins didn't begin with Fort Collins," CSU professor and archaeologist Jason LaBelle said. "It didn't begin with the establishment of Camp Collins or the military camp everybody associates it (with). This place has been used 13,000 years."

Unearthing Northern Colorado history

On a July day in 1924, a Fort Collins judge, his teenage son and a family friend happened upon history.

While exploring what was then William Lindenmeier’s ranch north of Fort Collins, the trio of amateur archaeologists spotted the first of what would end up being many carved spear points.

In 1926, a similar archaeological site in Folsom, New Mexico, was excavated, turning up a smattering of bison bones and spear points and introducing the world to the concept of “the Folsom man” — a culture of hunter-gatherers who occupied much of central North America 12,000 to 13,000 years ago.

A recent development: Native group outraged at sweat lodge's removal from former Hughes Stadium land

New Mexico’s Folsom site was rich in bison bones and spear points but left no signs of any former campsites, indicating that Folsom people were widely mobile bison hunters, LaBelle said.

“And for many years, that formed kind of a caricature of what that culture looked like,” LaBelle added. “These bison-hunting peoples that moved across the Great Plains and Rockies and Southwest 12,000 to 13,000 years ago.”

When the Smithsonian Institution finally started excavating Colorado’s Lindenmeier site in 1934, it found multiple archaeological hot spots that contained animal bones, stone tools, hide-working equipment, bone needles used for sewing water-tight winter clothing and hematite, which was used to cut red ocher for dye, according to LaBelle.

“… So here’s the irony, right? The second Folsom site excavated is the complete opposite to the first one excavated,” he said, noting that where New Mexico’s Folsom site shed light on bison hunting in the late Ice Age, the Lindenmeier site offered a wholly different peek into the Folsom people's domestic activity.

Other sites found in Northern Colorado over the past century indicate that people of the area have been foragers or hunter-gatherers for nearly all of the area’s archaeological record, according to LaBelle.

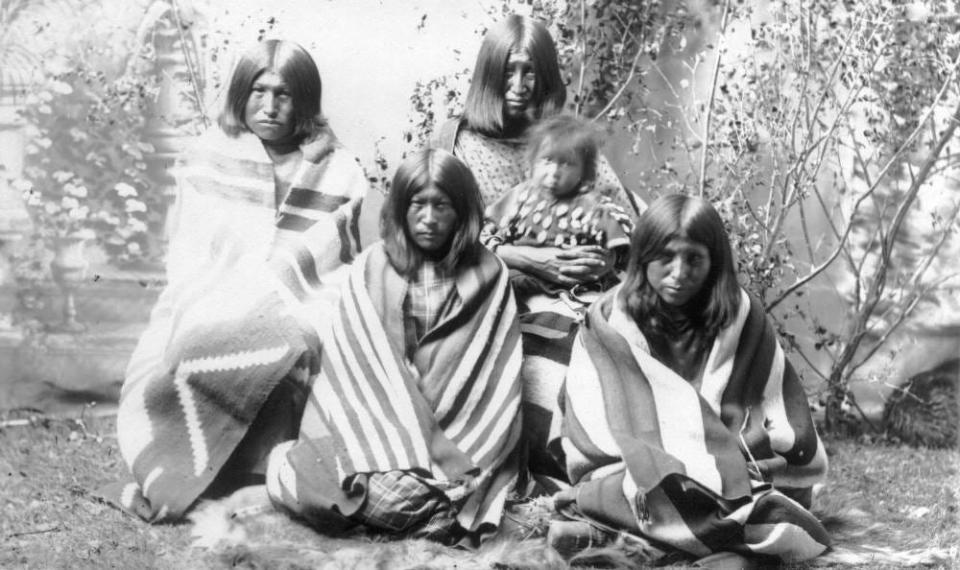

In the past 400 years alone, Northern Colorado’s Cache la Poudre Valley was home to a succession of Indigenous people from the Upper Republican, Dismal River Apache and proto-Shoshone culture groups and, later, Arapaho, Cheyenne and Ute tribes, according to People of the Poudre, a historical study of the Cache la Poudre River National Heritage Area.

In the winter, they would likely reside in encampments on mountain flats along the Front Range. When the snow melted and local plant life returned, it’s believed many of these groups spent their summers and falls foraging for plants and hunting bison and other animals — dedicating their days to processing their kills and building up their stores of food for the next winter.

“The hunter-gatherer lifestyle was really, really efficient and people lived that lifestyle really until the mid-19th century,” LaBelle said.

Native Americans and Euro-Americans meet

After roughly two decades of what — by many accounts — appeared to be a symbiotic relationship between Native American tribes and fur trappers who frequented the Cache la Poudre Valley, life in Northern Colorado took a hard turn in the mid-1800s.

In search of cheap land, gold, silver and other opportunities, more white settlers were moving west via popular routes like the Oregon, California and Mormon trails, according to Brian Carroll, a Fort Collins historian and author of the 2021 book about his city's namesake, "William O. Collins: From the Mayflower to the Rockies With Stops in Between."

Fueled by the growing philosophy of Manifest Destiny, many ventured west thinking they had a God-given right to the territory they planned to settle on, fueled by “divine support for this movement of ‘the land is there for everyone to have and enjoy,’ ” Carroll told the Coloradoan last month.

“Sadly, the definition of ‘everybody’ didn’t include the Native Americans who were already there,” he said.

With more white settlers passing through historically Native American land, hostilities rose between the groups in America's expanding West. In 1862, the U.S. Army commissioned the establishment of Camp Collins, a military outpost set just off the banks of the Poudre River to protect mail stagecoaches and settlers from bands of the area's Native Americans.

By 1864, the camp, which was named for Lt. Col. William O. Collins, was moved to what is now present-day Old Town Fort Collins.

From the late, great Barbara Fleming: A river and its verdant valley become Fort Collins

Native Americans — specifically a band of Arapaho led by Chief William Friday — remained in the area.

Friday had been separated from his tribe as a young boy around the early 1830s. He was discovered by fur traders and taken back with them to St. Louis.

"They found him on a Friday. That's how we got our last name," Chief Friday's great-grandson Hubert Friday told the Coloradoan last month from his lifelong home on Wyoming's Wind River Indian Reservation.

After learning to read, speak and write English, William Friday returned to Colorado and was reunited with his tribe. As one of the few English-speaking Arapaho tribal members, he was able to communicate with Euro-American settlers of the area.

"He used to help settlers. The wagon trains that came through ... he protected them with his band," Hubert Friday said. "They wanted to make him a war chief, but he didn't want to be a war chief. He wanted to be just a leader."

After largely maintaining their usual way of life in an ever-changing West, things “really started to change” for Northern Colorado’s Native American tribes with the signing of the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie, LaBelle said.

“…That is the treaty that really divvied up the western plains into tribal territories,” LaBelle said.

Within a decade, gold was discovered in Colorado, bringing more white settlers into Native American treaty lands. By 1861, the Treaty of Fort Wise was signed, cutting the Native American territory agreed upon in 1851 down to a fraction of its size.

“So in a very short period — less than 15 years — you go from complete autonomy and no control over Native American populations to a series of treaties that make smaller and smaller parcels of land that they can operate within, according to the federal government,” LaBelle said. “And this was going to culminate at the Sand Creek Massacre.”

The Sand Creek Massacre took place on Nov. 29, 1864, when Col. John Chivington led almost 700 volunteer U.S. soldiers in an attack on an unsuspecting Cheyenne and Arapaho village along Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado. Upwards of 230 Arapaho and Cheyenne tribal members were killed, according to the Sand Creek Massacre Foundation.

Roughly five years of sustained conflict between the U.S. government and the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Lakota and Sioux nations followed, LaBelle said.

Despite efforts by Chief Friday to get a swath of land along the Poudre River designated as a reservation by the federal government, that proposal failed and Native American occupancy of the Cache la Poudre Valley informally ended around 1868 when Friday’s band of Arapaho were pushed north to Wyoming's Wind River Indian Reservation, according to Carroll and People of the Poudre.

After thousands of years of living off of Northern Colorado — returning with the seasons, setting up camp, hunting in its meadows and foraging in its forests — Native American tribes were removed from their ancestral home.

Some of the age-old tools once used by the earliest inhabitants, from spear points used for hunting to pigment stones used for dyeing clothes, now sit at the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery.

And while it lived well into the 1950s, the Arapaho's council tree — a gnarled cottonwood where Chief Friday met with other tribes and bartered with white settlers — was ultimately damaged and removed from its lifelong home just outside what is now Fort Collins' Arapaho Bend Natural Area.

About five years ago, Hubert Friday sat along the Poudre River near the council tree's former site for a video interview with The Poudre Heritage Alliance. Now 85, he doesn't get to Fort Collins as much as he used to, but he remembers visiting the area nearly all his life.

And he remembers how it felt to sit along the rushing river, to walk on the same land his great-grandfather did.

"It felt like home," he said.

Celebrate Native American heritage in Fort Collins

The Northern Colorado Intertribal Pow-wow Association is hosting the 28th Annual Contest Powwow and Art Market next month in Fort Collins, aimed at preserving and honoring Native American cultures through music, dance, food and art.

When: 4-10 p.m. April 8, 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. April 9, and 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. April 10

Where: Northside Aztlan Community Center, 112 E. Willow St., Fort Collins

For more information, visit ncipa.weebly.com.

Erin Udell reports on news, culture, history and more for the Coloradoan. Contact her at ErinUdell@coloradoan.com. The only way she can keep doing what she does is with your support. Thank you for subscribing.

This article originally appeared on Fort Collins Coloradoan: Fort Collins history: A look at area's early Native American life