Former TCU professor worked on real-life ‘Oppenheimer’; not his first brush with Hollywood

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

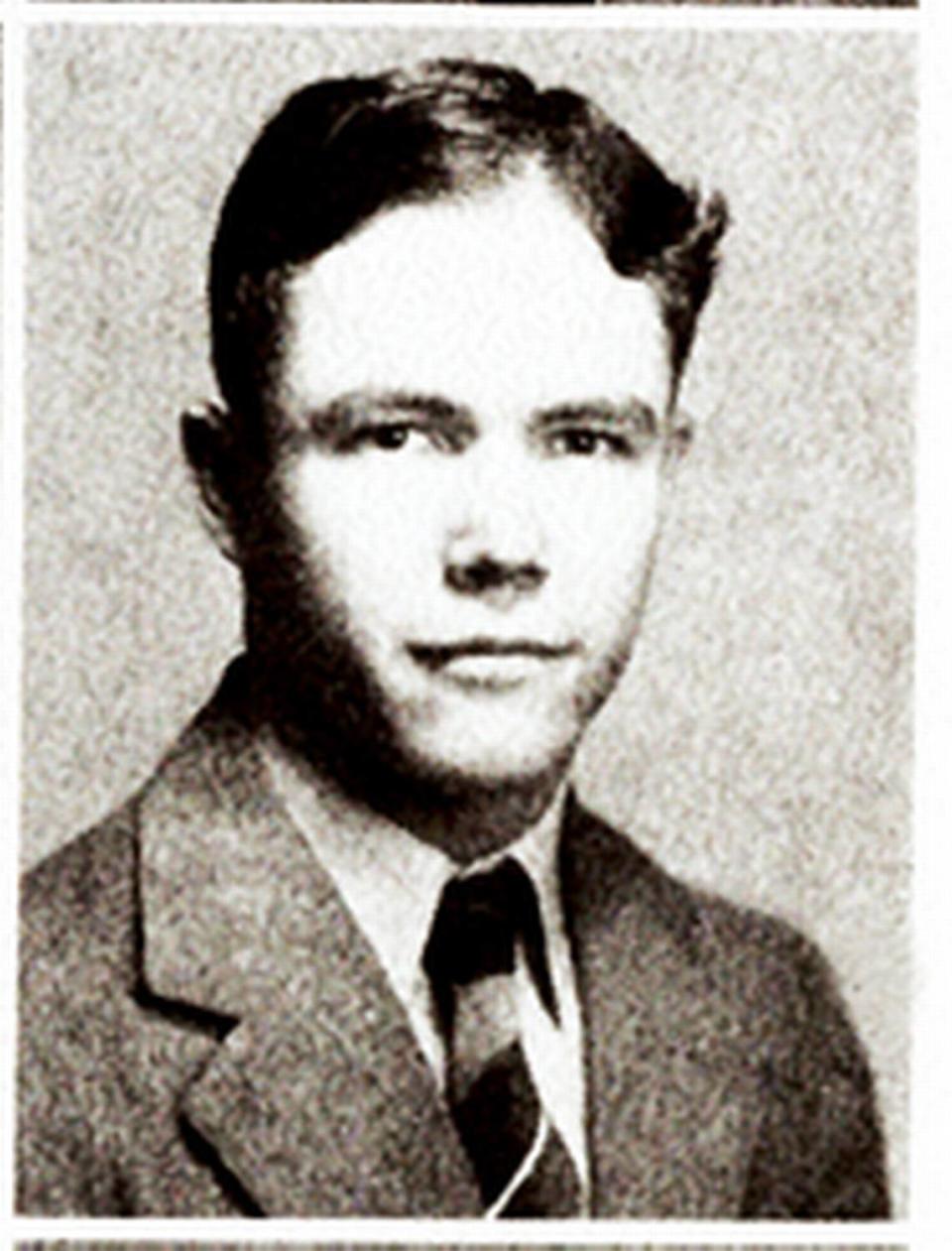

Harrison Miller Moseley was many things, and at the top of an impressive list was his work as mathematician for the Manhattan Project.

“I was just doing my job,” he modestly told TCU Magazine back in a 2008.

After his work building the bomb was done, he realized that his skills were a part of something that would change the course of history.

When “Oppenheimer” snagged seven Oscars Sunday night, Moseley’s work on America’s first atomic bomb took a Tinseltown shine. Not that the life of the TCU alumni and professor needed any more burnishing. His young life as one of the “12 Mighty Orphans” at the Masonic Home and School of Texas was featured on the big screen across America in 2021.

⚡ More trending stories:

→ Texas to 'spring forward': When daylight saving time begins

→ How a six-pack of beer, $100 got rescuers to pull pig out of thorns.

→ Want to make $359K a year working from home? Here's a list of jobs.

Moseley’s time at Los Alamos, New Mexico, with the scientists searching and building the world’s most powerful weapon was a secret until he shared details of his explosive past nearly a dozen years ago.

So, how’d he get to the high desert of New Mexico?

It was a matter of whom he knew. As a doctoral candidate at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, he studied under Nathan Rosen who happened to know one Albert Einstein. The famed physicist convinced Rosen to work on the Manhattan Project, and Rosen took his chemistry and physics apprentice West with him to Los Alamos.

After Moseley’s work with Rosen ended, he took a step back and settled down, returning to his alma mater, Texas Christian University, to become a chemistry and physics professor.

So, who was Harrison Miller Moseley?

Moseley lost his father at the young age of 7 — finding his way to Fort Worth to attend the Masonic Home, a school for orphans of late masons. He discovered a passion for football, where the undersized Moseley excelled against much larger competition.

His was team nicknamed the “Mighty Mites” and were the proverbial underdogs, yet managed to beat teams with bigger and better athletes. The rag-tag crew tied for a Texas state title and won eight games a year between 1928 and World War II. The team’s exploits were made into a movie based on the book of the same title by Jim Dent.

Even with his teams prowess on the gridiron, Moseley’s scrawny 126-pound frame was never going to net him a football scholarship, and he needed a way to pay for college.

Well, thank God he was a genius.

TCU, down the street from the Masonic Home, wanted Moseley and gave him a full scholarship and “laundry money.” In return, Moseley had to work for the university for 15 hours a week.

From there, he declared a major of chemistry and physics, graduating top of his class. As a doctoral candidate at UNC, Chapel Hill, Moseley worked on a project separating isotopes for the U.S. Navy.

“Eventually he enlisted in the Navy and began working in the Naval Research Laboratory, then in the midst of a huge World War II push to develop a thermal diffusion process to supply the 235-uranium isotope used for the first atomic bombs.” according to Rick Water, assistant editor at TCU Magazine.

His work on the world’s first atomic bomb began.

Life after the Manhattan Project

After the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Moseley realized the gravity of his work. It was greater than he ever imagined. He searched for a simpler life.

The perfect opportunity arose when Newton Gaines, Moseley’s former TCU professor, asked him to come back to Fort Worth and teach. He began as professor in 1950, teaching at TCU for the next 40 years.

He retired in 1990, enjoying a life with his wife, Doreen, and his children and grandchildren. Moseley was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease a few years later. He died in 2014.

He was remembered not only for his accomplishments and contributions but also for a gentle spirit and loving heart.