The Forgotten Legacy of Bill Lucas

On September 19, 1976, the Atlanta Braves owner Ted Turner promoted a man named Bill Lucas to vice president of player personnel. Though Turner, somewhat oddly, kept the official title of general manager, Lucas assumed the job's responsibilities, overseeing the Braves’ roster. As a former minor-league player who had climbed through Atlanta's front office, Lucas was a typical hire, except for one fact: Unlike every other man to ever run a Major League Baseball franchise until that point, he was black.

Nearly three decades after Jackie Robinson had become the first black player in the modern Major Leagues and two years after Frank Robinson had become the first black on-field manager, Lucas had shattered another barrier. Sadly, Lucas’s tenure as the Braves’ top baseball executive didn’t last long: He died at age 43 of a sudden brain hemorrhage in 1979, after only two and a half years on the job. The Braves, moribund when Lucas took over, wound up winning the National League West in 1982 with a roster Lucas helped build.

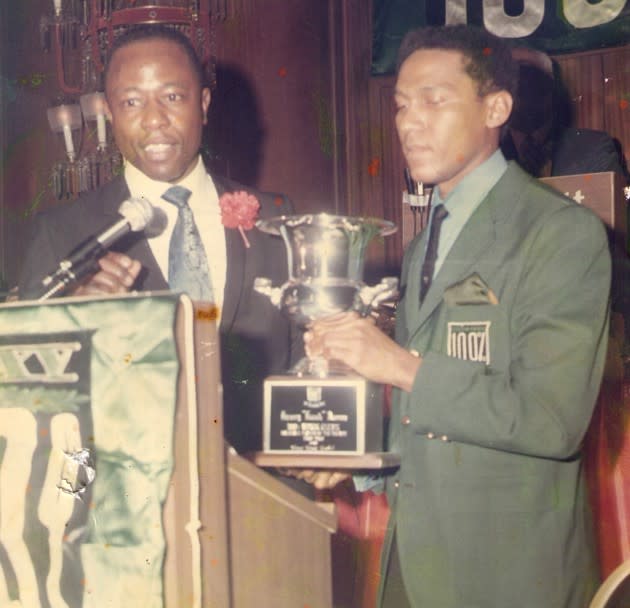

Forty years have passed since Lucas’s first season as Braves’ GM, and in February the team celebrated the anniversary in a ceremony at the brand-new SunTrust Park. There, the Braves announced several plans to commemorate Lucas, including a new apprenticeship in his name aimed at diversifying the front office. But despite the recent plaudits, Lucas remains a mostly forgotten figure in the sport’s history, with little name recognition outside Atlanta—even in hardcore baseball circles.

It’s fair to wonder how much Lucas’s relative anonymity owes to the dearth of black executives invited to follow in his footsteps. Since his death, there have been hundreds of black Major League players and several dozen black managers but only five black GMs. Today, there are no black general managers (though two black men, the Chicago White Sox’s Kenny Williams and the Miami Marlins’ Michael Hill, have been promoted from GM to higher positions). In April, the Institute of Diversity and Ethics in Sport handed MLB teams a C on its annual report card for racial hiring practices when it comes to general managers.

Recommended: How Al Franken Got America to Take Him Seriously

Lucas, according to those who knew him, was a bright baseball mind and a willing pioneer. By all accounts, he did everything he could to open the door for fellow black executives. But four decades after Lucas became the highest-ranking black official in baseball, the sport faces many of the same problems it did before he came along.

* * *

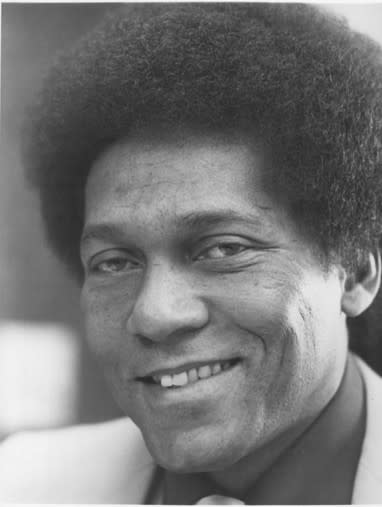

At first, Lucas rejected his status as MLB’s first black general manager, his widow Rubye tells me. His race wasn’t what mattered, he figured. He was a hard worker with a quick mind and an encyclopedic knowledge of baseball, and that’s how he wished to be known. But once his first Spring Training as GM rolled around, his attitude began to change. A lifelong Jackie Robinson fan, Lucas soon realized he, too, had made history. “It really, really, really, really became important to us that perhaps his purpose in life was to show that African Americans could be in high positions in sports, and especially baseball,” Rubye, now 80, remembers.

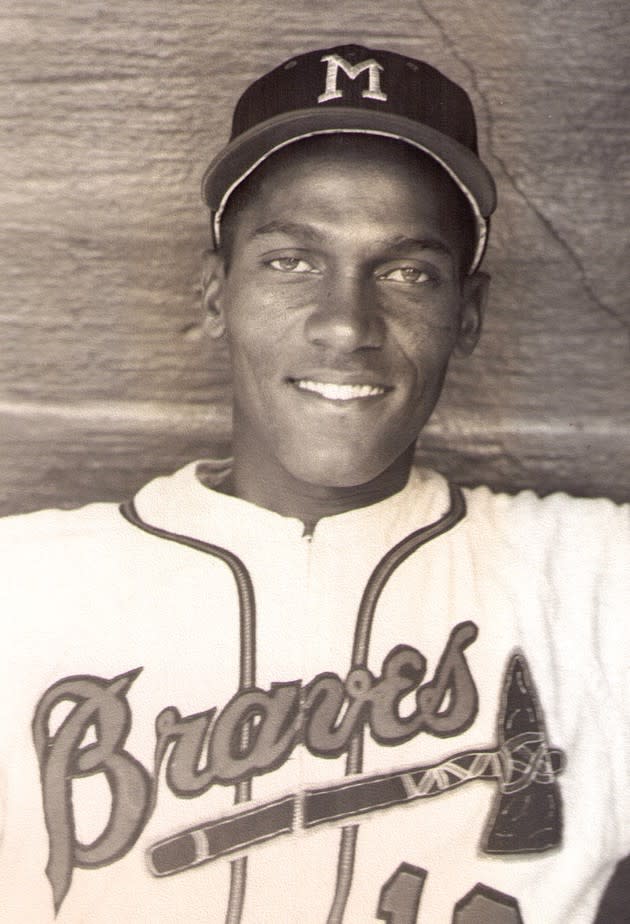

Lucas was born on January 25, 1936 in Jacksonville, Florida, and grew up in a housing project with working-class parents. His family emphasized education throughout his childhood, and he attended Florida A&M University, where he starred as an infielder and met Rubye. After college, Lucas signed with the Milwaukee Braves but soon put his career on hold to serve two years as an Army officer. He returned for four more seasons in the Braves’ farm system, topping out at the Triple-A level before retiring in 1964. Paul Snyder, who played with Lucas in the minor leagues and later worked under him in the Braves front office, remembers him as one of the few players on the team bus who read books “that had no pictures.”

When Lucas quit playing, the Braves, who were preparing to move from Milwaukee to Atlanta, hired him as a public-relations liaison to the black community. Lucas quickly impressed the team brass in that role and soon jumped to player development, working his way up to farm-system director in 1972.

Recommended: 'House of Cards' Season 5, Episode 13: The Live-Binge Review

Dusty Baker, who came through the Braves’ system in the late 1960s, remembers how nervous he was to play in the South and how Lucas’s mentorship eased his worries. Baker says Lucas modeled how to get by as a black person while “maintaining your honor and dignity as a man.” “He would tell you the truth, but he couldn’t tell you everything, and you had to be smart enough to read between the lines,” recalls Baker, who now holds the MLB record for wins by a black manager.

“He knew baseball. He could talk the language, he understood players ... and he had a good personality.”

By the time he was farm director, Lucas was already a pioneer. Though every team had integrated on the field, MLB front offices remained almost entirely white. If black men were ever hired, they were rarely promoted. In the 1950s, for example, the New York Giants scout Alex Pompez had signed future Hall of Famers Orlando Cepeda, Juan Marichal, and Willie McCovey and still failed to advance out of the international scouting department.

The baseball historian Leslie Heaphy figures there was a simple reason Pompez and other black executives failed to break through. “It’s that whole idea of the boss,” she says. “A lot of it has to do with power issues and our long-standing issues with race in this country, looking at African Americans, historically, as being somebody who worked for you, not who you worked for.”

Yet while most of baseball rejected the possibility of black front-office executives, Lucas thrived with the Braves. He was promoted to vice president of player personnel in 1976 after the incumbent, John Alevizos, resigned. (Though Lucas never officially held the GM title, baseball history has rightly given him that distinction.) Some of Lucas’s rise owed to a perfect storm of place and circumstance—the Braves, unlike many teams, had a strong black fan-base and a comparatively open-minded owner in Turner. And, as even Lucas admitted, it didn’t hurt that his sister had married franchise icon Hank Aaron.

But such explanations sell Lucas short. Those who knew him say Lucas was a natural leader with the type of affable, disarming personality that endeared him to people regardless of race. And, of course, he was a battle-tested baseball man, who had proven his value. “He knew baseball,” says Dick Cecil, a longtime Braves executive who first hired Lucas back in the mid-’60s. “He could talk the language, he understood players, he understood the minor leagues, he understood development. And he had a good personality.”

Recommended: With 'Wonder Woman,' DC Comics Finally Gets It Right

In Lucas’s brief tenure as general manager, he called up budding superstar outfielder Dale Murphy, drafted All-Star third baseman Bob Horner, and hired future Hall of Fame manager Bobby Cox. Rubye remembers how Bill would fight Turner’s notorious impulsivity with reason and prudence. “They had a wonderful relationship,” Rubye says of Lucas and Turner. “Ted respected him because he would stand up to him and say, ‘No, that’s not the way we’re going to do it. You don’t know a thing about baseball, so let me handle it.’”

“He wasn’t here for the good times, but we were here for the good times.”

“He would say the things to Ted that nobody else would say,” Lucas’s daughter Wonya, a teenager during her father’s tenure as GM, tells me. “He would say, ‘I don’t care if they fire me.’ To him it was about doing the right thing, and he operated with no fear. It doesn’t matter if you’re Ted Turner, or if you’re a guy on the grounds crew.”

But after building one of the best farm systems in baseball, Lucas died before his roster could flourish. According to The New York Times, Lucas had complained of pain in his chest and arms, but Braves doctors had found no problem before the hemorrhage hit.

Snyder, who went on to work for the Braves until 2007, credits Lucas with setting up the franchise for success in the early ’80s and even into the ’90s, when the team won five NL pennants and a World Series. “He planted a seed, and we just carried through with it,” Snyder says. “He wasn’t here for the good times, but we were here for the good times, and I think a lot of that was because of [Lucas’s] direction in the beginning.”

* * *

Though Lucas broke ground as baseball’s first black GM, his hire hardly ushered in a wave of non-white executives. The next black GM didn’t come along until 1988, when Bob Watson was hired to run the Yankees. After that came Kenny Williams in 2000; Michael Hill in 2007; Tony Reagins in 2007; and Dave Stewart in 2014. Today, Williams and Hill are still around in different roles, but no black men—and next to no people of color—hold the title of general manager.

The lack of African American general managers in 21st-century baseball has many explanations, beginning with the declining involvement of black people at all levels of the sport. But, without question, the path toward a front-office position has changed in the past 15 years, in a way that seems to deter diversity.

“Whenever you have a pioneer, it doesn’t detract from their legacy to say the floodgates don’t immediately open.”

Unlike in Lucas’s day, when most executives were ex-players, only about half a dozen current general managers played professional baseball, and just one of that group made it past the Double-A level. Most top baseball executives now have profiles like that of the current Braves GM John Coppolella, who studied business administration at Notre Dame, then turned down a $90,000-a-year job for an $18,000-a-year internship in the Yankees’ front office before jumping to the Braves and becoming general manager in 2015 at age 37.

A 2016 study by Kate Morrison and Russell Carleton of the statistical-analysis website Baseball Prospectus found less than 10 percent of all current American League front-office executives were former players. Meanwhile, about a third of those executives had started their careers as interns, more than half had attended private universities, and nearly a fifth had studied in the Ivy League. Among executives who had graduated college within the previous 10 years, a whopping 72 percent were former interns.

It seems Lucas’s path—from player to player development staffer to general manager—has been nearly replaced by one that looks like Coppolella’s. This shift in how one becomes a baseball executive has had dramatic implications for who can become a baseball executive. To rise through the front-office ranks today, you probably need a degree from an elite private university. You likely need a familiarity with complex statistical concepts. And you almost definitely need a tolerance for internships and entry-level positions that pay little or nothing at all.

The latter requirement in particular discourages candidates of color who can’t afford to go years without a livable wage in pursuit of a distant dream. Though overt racism in the sport has declined (though not entirely vanished), structural barriers that hinder the advancement of black executives remain.

But to Heaphy, Lucas is a true trailblazer regardless of how many black general managers have come after him. “Whenever you have a pioneer, it doesn’t detract from their legacy to say the floodgates don’t immediately open,” Heaphy says. “What is more important is that the doors don’t close. And that his success made it possible for other teams to say, when the right person came along in the right situation, that yes, this is something we can do.”

Lucas’s family knows the legacy Bill left. They’ve heard longtime baseball men like Dusty Baker and Bob Watson say they owed their careers to Lucas’s example. They’ve heard people in Atlanta swear by the impact he had there. And they’ve watched as the homegrown approach to team-building that Lucas believed in has become a core tenet of the Braves’ franchise. Lucas’s place in history is perfectly secure, even if baseball sometimes seems to have forgotten it.

Read more from The Atlantic:

This article was originally published on The Atlantic.