The forgotten hero: Uncovering Rhode Island's lost Medal of Honor recipient from WWII

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Back in March, I wrote a column about the Medal of Honor awarded to WWII hero George Peters from Cranston. Peters was killed in Germany in March 1945.

In that column, I referred to him as “… one of only two Rhode Islanders to earn this award during World War II,” with the other being Sgt. William G. Fournier of South Kingstown, killed at Guadalcanal in January 1943.

I received an email shortly thereafter from Kathie Edwards, who took gentle issue with my assertion that only two Rhode Island soldiers had earned our nation’s highest award during WWII.

“… note that Robert Waugh of Cumberland was also a WWII MOH recipient.”

Rhode Island's lost Medal of Honor recipient

Curiosity piqued, I looked up Lieutenant Waugh – who did, in fact, earn the Medal of Honor in Italy in 1944. However, according to federal records and the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, his medal is accredited to Maine, not Rhode Island.

“He was my former husband’s uncle,” Kathie continued. “My ex’s name is Robert Waugh Edwards. [The Medal was] definitely a source of pride for the family!”

Bob Edwards now lives in Tennessee, so I contacted his brother John, who lives in Plainville, Massachusetts, just across the border from Cumberland.

“The medal was a fixture in my grandfather’s house,” John told me. “He lived in Wrentham, and my brothers and I spent a lot of time there.

“We didn’t know the significance of the medal until much later in life.”

Background and early years

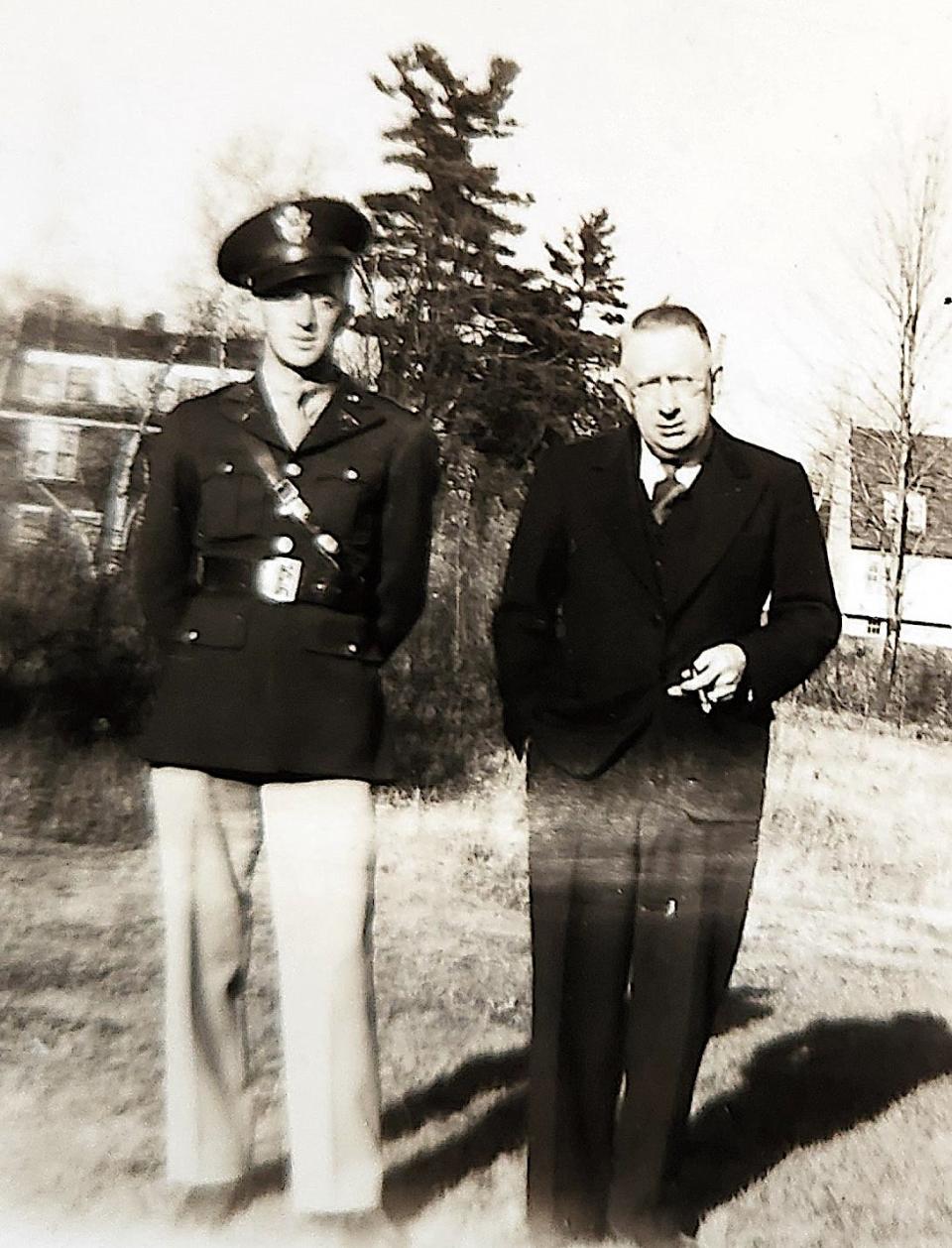

Born Jan. 16, 1919, Bob was raised in the Ashton neighborhood of Cumberland, where he attended grammar school. He was the youngest of three children. Bob’s brother, John, was four years older, and his sister, Mildred, was two years older.

John Sr. was a foreman in a yarn mill, and the family moved around quite a bit as John went from job to job during difficult financial times.

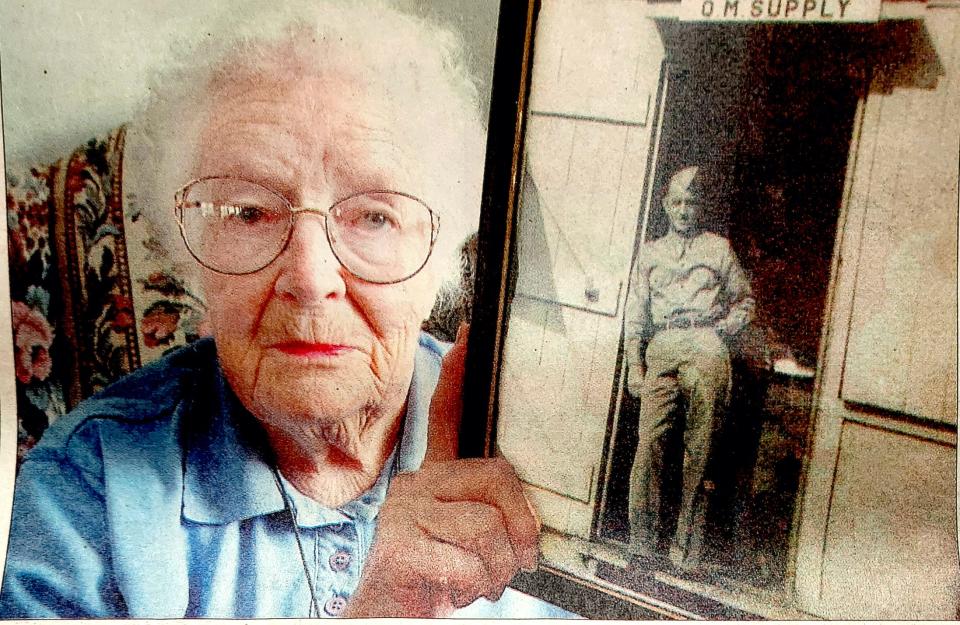

In 2003 the Attleboro Chronicle interviewed Mildred. “Robert was hell on wheels as a boy,” she said. “He skipped school regularly. … My brother was really smart, but he didn’t want to use it.”

Bob graduated from Cumberland High School in 1936. He went right to work in the tool department of the Howard & Bullough American Machine Company in Attleboro.

After graduating from Cumberland High, a move to Maine

In 1937 his father found a job at Edwards Manufacturing, a cotton mill in Augusta, Maine.

Older brother John stayed in Rhode Island to complete his studies at Rhode Island State College. It is likely that Mildred stayed in state as well, since she had just enrolled at Rhode Island State Teachers College.

Shortly after arriving in Augusta, Waugh was hired as a machinery overhauler in his father‘s department, and on April 4, 1938, he enlisted in the Maine National Guard.

According to Mildred, he enlisted first, then told his family.

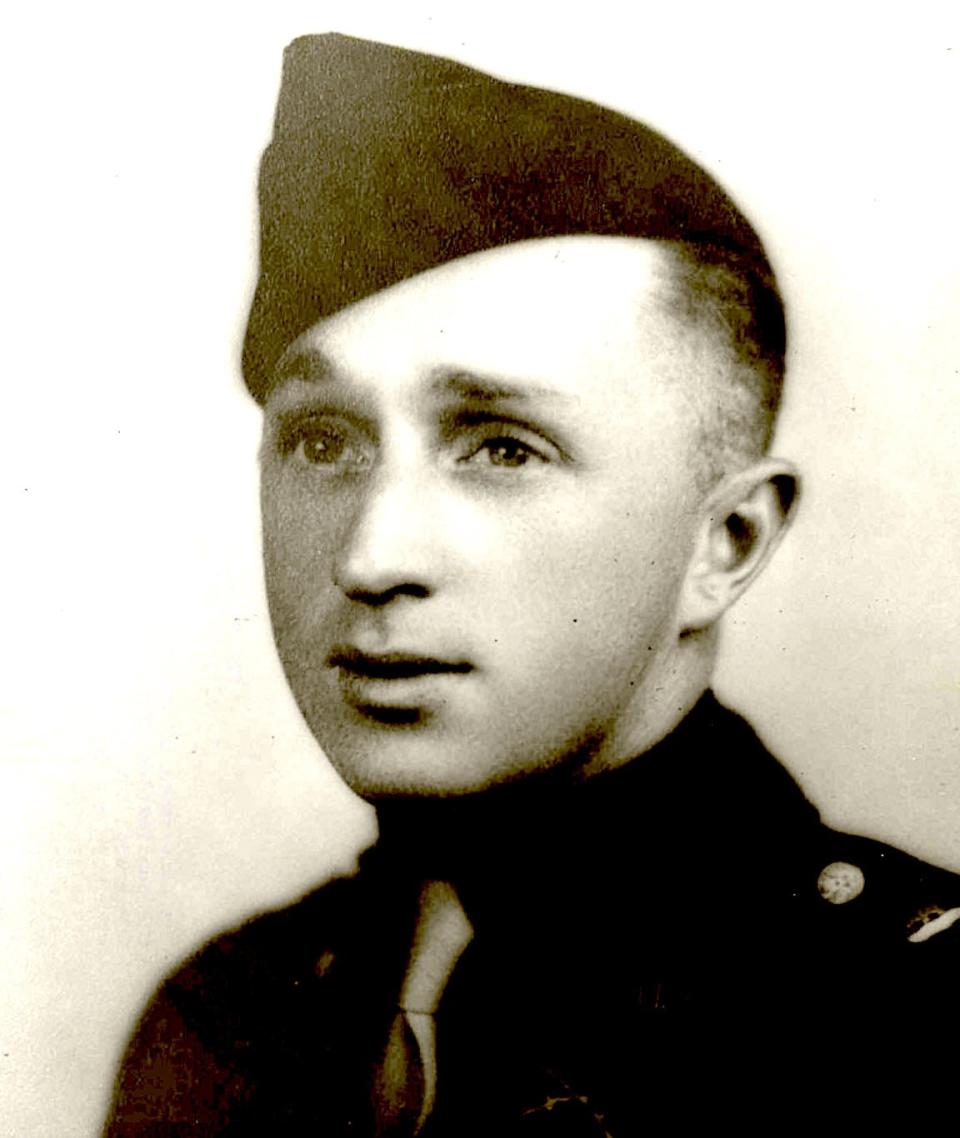

On Dec. 1, 1939, he entered federal service, joining the Army Air Corps in hopes of becoming a pilot. He started out at Langley Field in Virginia as a line mechanic. In February 1941 he was transferred to Losey Field in Puerto Rico, where he became a supply sergeant.

When the Air Corps rejected his application for air cadet training, he elected to transfer to the infantry and apply to Officer Candidate School. He was assigned to a training cadre at Camp Wolters, in Texas. His appointment to OCS came through, and he graduated at Fort Benning in December 1942.

He was assigned to the 339th Infantry Regiment of the 85th Infantry Division at Camp Shelby, Mississippi.

Known as the “Custer Division,” they moved to Camp Coxcomb, California, in August 1943 for desert warfare training. In October, the division was transferred to Fort Dix, New Jersey, for final preparations before deploying to North Africa.

'Goodbye, Uncle Al. I won't be back'

Mildred says Bob visited an uncle in New Jersey before shipping overseas. He shook his hand and said “Goodbye, Uncle Al. I won’t be back.”

The 85th arrived in Casablanca on Jan. 2, 1944. After amphibious training in Algeria, they embarked for Naples, arriving on March 27.

Waugh wrote when he could and sent part of his pay back to his family. He asked that some of it be spent on Mildred’s summer school tuition at Boston University.

After the landings at Salerno and Anzio, the Allies pushed toward Rome. The 85th Division was assigned to break through the strong defensive positions of the Gustav line.

Largely through Waugh’s efforts, the 339th captured an anchor point in the Gustav Line in mid-May 1944.

One night in May he eliminated six bunkers, one after the other, as his men provided covering fire. He tossed grenades into each, flushing the German defendants and dispatching them if they did not surrender as they emerged.

Then, he reorganized the position and redirected the German machine guns to support American attacks on adjacent hills.

On May 14 he attacked two German pillboxes at the top of the hill, using the same tactics. The Army reported, “Almost single-handedly Lieutenant Waugh broke the Gustav line, killing 30 Germans, capturing 25 and destroying six enemy bunkers and two pillboxes.”

Waugh and his men had overwhelmed an entrenched German force twice their size.

Although he survived this harrowing experience almost unscathed, he died five days later when leading his men at Itri. He is buried at the American cemetery in Nettuno, near Anzio.

Processing of his award was unusually fast; Maj. Gen. Henry Terrell, Jr., commanding officer of 22nd Corps, presented the medal to Waugh's family in October 1944.

In June 1994, on the 50th anniversary of the Gustav Line battles, President Bill Clinton visited Waugh's gravesite.

So why is Waugh's medal accredited to Maine?

Because Waugh enlisted in Maine, the military considered Maine his home of record. Even though he was born in Rhode Island and spent the first 18 years of his life here – and his name is engraved on the family gravestone in Central Falls – he is still a Mainer in the eyes of the Army.

His burial record at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery lists Maine as his home, and Maine is marked on his gravestone.

When he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1944, the War Department identified him as “1/LT Robert T. Waugh of Augusta, Maine.”

The Aug. 14, 1944, Portland paper ran a page-wide banner headline: “Augusta Lieutenant Killed 30 Germans, Captured 25 Before Dying in Italy.”

Still, his family considered him a Rhode Islander long after his death

Army records suggest the family (first his parents, then his sister) petitioned to have his remains transferred from Italy to Rhode Island, which they considered to be his true home.

One researcher stated that other Army correspondence suggests the family took the request further, asking that “Maine” be replaced by “Rhode Island” on his overseas grave marker.

Coming full circle, his parents returned to Rhode Island and are buried in Moshassuck Cemetery in Central Falls. Bob’s name is etched on another Waugh family gravestone there, even though his remains are still in Italy.

There are plaques in his honor at Cumberland High School, Cumberland Library, and the house in Ashton where he was born.

In 1988 Rhode Island dedicated a 10-foot-high monument at the Veterans Cemetery commemorating 36 Rhode Islanders who earned the medal since its establishment during the Civil War.

On that monument, Lieutenant Waugh is proudly and properly identified as a Rhode Islander.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Robert Waugh: RI's lost Medal of Honor recipient