Florida is weird. Thanks to coronavirus, its primary will be, too

TALLAHASSEE — Door knocking? Nope. Surrogate stops? Canceled. The bubbly? Corked. Even the candidates will be AWOL.

Florida, a state famed for its weirdness, is preparing for one of its weirdest election days on Tuesday, when Democrats and Republicans will brave a pandemic to cast primary ballots for their presidential nominees.

With two popular candidates on the ballot, Democrats were hoping to deliver a show of force against President Donald Trump with pumped-up turnout and lots of noise. Instead, they’ve had their mojo stolen by the coronavirus.

Florida is a presidential election year crown jewel, a delegate-rich state that does double duty as the nation’s largest battleground. It’s expensive and difficult to flex institutional and infrastructure muscle in the state, which serves as a barometer of any campaign’s viability.

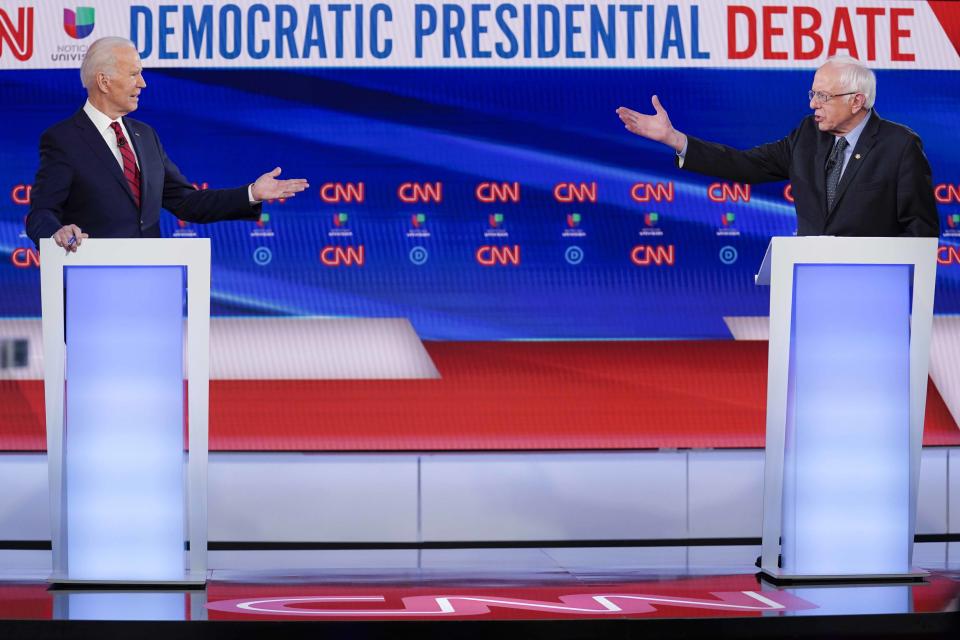

Still, neither Joe Biden nor Bernie Sanders have campaigned here this year, and neither will be glad-handing Tuesday. Democratic get-out-the-vote operations are all but halted, and for the first time in memory there will be no Election Day parties.

As the country hunkers down to avoid the coronavirus, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, on Monday made a push to postpone his state’s Tuesday primary, a plea a judge rejected late Monday. Illinois and Arizona, which also vote Tuesday, are at full speed.

And in Florida, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis said he’s not going to panic.

“We’re definitely voting,” he said Saturday at a coronavirus briefing. “They voted during the Civil War. We’re going to vote.”

Besides, he said, most ballots probably have been cast in early voting already. And neither party’s primary, he noted, are going to be cliffhangers.

Florida has a reputation for botched elections — from hanging chads in 2000 to a confusing recount in 2018 that led to the ouster of two South Florida election supervisors.

This time around, polling places could present the biggest challenge. In an effort to protect elderly populations most at risk from the coronavirus, DeSantis has shut down voting sites at nursing homes and assisted-living facilities.

Democrats are riled up.

“We agree with the governor’s decision. We think it’s good policy to protect at-risk populations,” said Juan Peñalosa, executive director of the Florida Democratic Party. “But there is no list of impacted voting locations. It’s information we want to help communicate to voters, but we were told by the governor’s office there is no list, and won’t be before Election Day.”

So Peñalosa’s staff and volunteers are making their own list. They’ve reached out to all of the state’s 67 county election offices to find out where polling sites will be closed.

“We are compiling a list and have already started communicating to impacted voters,” Peñalosa said.

Then there’s the problem of staffing. Poll workers afraid of being exposed to the virus are dropping out. That’s on top of the election coinciding with spring break — many workers have begged off duty this year due to family obligations.

Pasco County elections supervisor Brian Corley said he started “hemorrhaging” poll workers after a county resident tested positive for the coronavirus.

“I can’t blame them,” Corley said. “A lot of them are senior citizens.”

Corley said he’s lost 175 workers so far, and has turned to the local sheriff, schools and county government to find people to fill their spots. School resource officers from the Pasco County Sheriff’s Office will be among those reporting for duty on Tuesday, along with teachers and other county employees.

“We can’t get to them fast enough,” Corley said.

Still, election supervisors remain optimistic the day will go smoothly, in part because turnout won’t be that high.

“We knew going in this was going to be challenging,” said Orange County Supervisor of Elections Bill Cowles.

And Corley said he’s doing the unthinkable — encouraging voters to not show up, especially if they’re sick or at risk.

“If anyone is unsure, don’t go to the polls, as much as it pains me to say that,” Corley said. “Elections are wonderful, but this is a political party nominating contest.”

Campaign operations also are improvising as the coronavirus creep sets in.

Rather than emphasizing last-minute campaign and policy talking points, or feverishly ramping up their face-to-face ground game, campaigns are employing public-service-type announcements.

Entire operations have gone virtual. Digital events have replaced rallies, in-person fundraising has been canceled, and election night parties just won’t happen.

Because neither race is close — Biden has lapped Sanders in state polls and Trump has no serious challengers — any impact on the actual results will be minimal as Florida copes with its slice of a global pandemic.

“Post South Carolina, when Biden surged in southern states, Florida experienced the same shift,” said Dan Newman, a Florida Democratic consultant who is unaligned in the presidential primary. “Basically, the race coalesced into Sanders and non-Sanders, and as a trusted national name, Biden was the beneficiary.”

More than a million Florida Democrats already have voted by mail or at early voting locations, surpassing pre-primary day turnout in 2016, when 889,207 Democratic voters cast ballots. That year, Hillary Clinton was still fighting off Sanders, her primary rival.

And even if Democratic turnout is low, it won’t give Republicans a valid reason to gloat, Newman said.

“I don’t think turnout in a presidential primary with neither campaign particularly active, and in a state that’s functionally already decided, and in the middle of a global pandemic is predictive,” he said, “of much.”