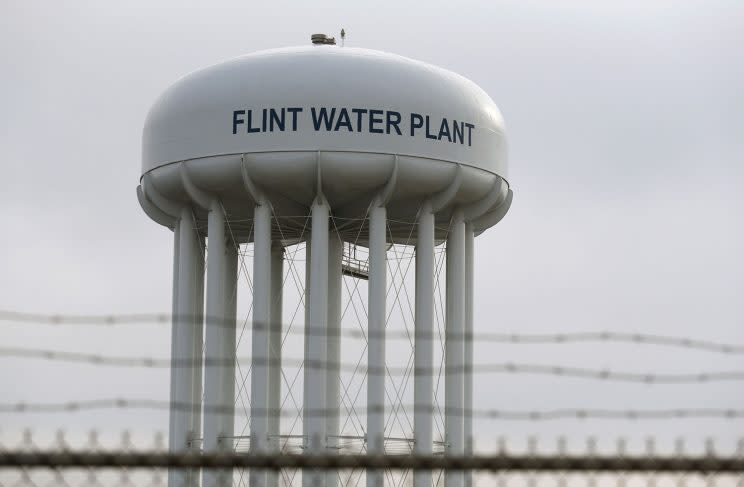

Flint water finally meets federal lead standards, officials say, but residents are wary

This week, Michigan state environmental officials announced that, more than two years after the city of Flint’s water supply was contaminated in an ill-conceived effort to cut costs, the amount of lead in Flint’s drinking water is now below the federal limit.

In a press release issued Tuesday, the head of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) deemed the finding “good news,” and Gov. Rick Snyder applauded “the remarkable improvement in water quality over the past year.” But in Flint, where faith in government has been shattered since city and state officials switched the city’s water supply from the Detroit municipal system to the Flint River, the announcement is hardly cause for celebration.

“It could be true; it could not be true,” said local artist and activist Desiree Duell. “There’s just no trust about the water.”

Duell told Yahoo News that she stopped using the tap water in her house shortly after the switchover in April 2014, when, she says, the overchlorinated water coming through her shower caused her ear to bleed. Since then, Duell said, she’s had a filter on her shower, a water cooler in the kitchen, and bottled water everywhere else. The only time she or her 11-year-old son use tap water is to wash dishes and flush the toilet.

“They called us crazy,” she said. “I haven’t had tap water since 2014.”

Although by October of that year the water’s high chloride levels had even prompted General Motors to stop using the tap water at its engine plant in Flint, it would take another year before Snyder declared a public health crisis in Flint and ordered the city to stop pumping water from the river and return to the Detroit system.

Since then, environmental experts reported a slow and steady drop in the level of lead in the city’s water.

Duell said that no one from the state has come to test her water for lead recently, and she can’t afford to do it herself. But, she insisted, “there are more things than just lead in the water.”

“My water right now smells like bleach,” she said. “That doesn’t seem safe to me.”

Melissa Mays, another Flint mother-turned-activist, agreed that the focus on lead, which causes brain damage in children, resulted in overlooking other contaminants. “Lead sucked all the air out of the room,” she said.

Back in January 2015, Mays and fellow Flint resident LeeAnne Walters co-founded the grassroots advocacy group Water You Fighting For, which helped bring Flint’s contaminated water to light, thanks to independent testing by Marc Edwards, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech.

“Initially when we started fighting we were fighting about the bacteria,” said Mays. (At least 12 people died in an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease between June 2014 and October 2015 that is believed to be related to the water supply.) “When we found the lead, they stopped talking about the other chemicals.”

More than 1,000 days after they were first exposed to improperly treated river water, health problems continue to plague Mays and her three sons, now ages 12, 13, and 18.

“I just found out today that my 18-year-old has blood pressure problems and the two younger ones have to go back to physical therapy” because of lead damage that, she said, has interfered with their bone growth.

The water currently coming through the faucets at her home “stinks so bad” and is “so caustic” that she said she spends about $40 a week to wash her kids’ clothes at a laundry outside of town.

Mays, who was one of the speakers at the Women’s March on Washington last weekend, is currently continuing to fight against what she sees as the state’s effort to do “everything they can to avoid fixing Flint.”

Last year, she teamed up with Flint-based Concerned Pastors for Social Action, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan to sue the city of Flint and the state of Michigan under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act. In November, Mays and the other parties to the suit won an injunction from a federal judge ordering city and state officials to begin delivering bottled water door-to-door to all Flint homes unless the government verifies that a faucet filter has been properly installed and is being regularly maintained.

At a hearing Tuesday afternoon, just a few hours after Michigan environmental officials announced that Flint’s lead levels had dropped below the federal limit, U.S. District Judge David Lawson said he was “unimpressed” by city and state officials’ “slow walking” in response to his November order to ensure that all Flint residents have access to clean drinking water, and directed them to return next week with a clear plan for compliance.

“I’m disgusted by the State’s pattern of neglect and dereliction of duty to the people of Flint as the water crisis enters its third year,” Pastor Allen Overton of the Concerned Pastors for Social Action said in a statement to Yahoo News Wednesday. “The State’s propaganda machine is working overtime to assure the people of Flint that there’s nothing to worry about the water. I’d appreciate seeing even half the effort being expended by the State to actually take care of the residents’ needs, including providing working filters, and bottled water for those whose tap water is unsafe to drink.”

Henry Henderson, the NRDC’s Midwest program director, also took issue with the state’s claim that Flint’s water “is now in compliance with federal law,” insisting that “the lead violations continue to this day.”

Mays also argues that the MDEQ’s latest announcement is “not accurate.” However, Virginia Tech’s Edwards told Yahoo News that, based on samplings of Flint water and on data from the MDEQ and the EPA, “it is clear that Flint’s water meets federal lead standards, and is also better than that of many other cities with old lead pipes,” despite the fact that residents are still being instructed to use filtered or bottled water. (Spokespeople for the MDEQ, Flint Mayor Karen Weaver, and the EPA’s Region 5 office in Chicago, whose jurisdiction covers Flint, reiterated both points in similar statements to Yahoo News.)

While people in those other cities might currently be drinking their tap water unfiltered, Edwards said that “a higher standard is being applied in Flint than in the rest of the U.S.” and suggested that “it is quite likely” that the new Flint standard “may soon become the norm for other cities, because it is clear that the existing lead and copper regulation is not adequately protective.”

Edwards is one of the only outside environmental experts trusted by most Flint residents. Last year, at the behest of the city’s residents, he was appointed by Gov. Snyder to the newly-established Flint Water Interagency Coordinating Committee, whose mission is to find a long-term solution to the water crisis.

Even with Edwards involved, however, it’s clear that state and local officials are still a long way from winning back the confidence of Flint residents.

“I’ve lost all trust in any government agency right now,” Duell said. “Unless all the pipes are replaced, I’m not going to trust it.”

Mays agreed, adding that, based on her experience, little effort has been made to rebuild that trust.

“We will never be able to trust them, and that’s their own fault,” she said.

Read more from Yahoo News: