Fixing the supply chain, improving U.S. manufacturing should be bipartisan issues

If there is a search for the Holy Grail of American politics, it’s finding issues that can bring bipartisanship and compromise back to Congress as a daily routine. Every now and then, Congress surprises us with a bipartisan solution as it did on the debt ceiling vote at the end of last year, but it is still mired in the quicksand of hyper-partisanship on too many of the challenges facing our nation.

As deep and wide as the chasm between the two parties seems to be, there is one issue that offers hope for bipartisanship and the good news is that Democrats and Republicans are coming together to deal with it.

This Christmas season in the second year of the pandemic served as a wake-up call to action. How many times did we visit a store or shopped online only to find that the perfect Christmas gift for someone special is not in stock or delayed in delivery beyond Christmas Day? Or bearing a significant increase in price?

In a recent report by American Marketplace on NPR, Christopher Lowe, chief economist with FHN Financial, called imported goods in short supply the driver of our current inflation woes.

Experts also cite capacity as a cause of our supply chain woes. Container ships were stacked up on the California coast and Boston as labor shortages caused by the pandemic made it difficult to unload the goods in a timely fashion. Many workers were laid off during the pandemic to make workplaces safer, but too many of them moved on to other jobs. Shipping suffered as a result. The Biden administration helped speed things up by pressing ports to expand their operations with longer hours, yet the supply chain still will need more time to recover.

The pandemic cannot shoulder the blame for all supply chain headaches. Free trade mania that allowed China to enter the World Trade Organization without guarantees that China would play according to the rules didn’t help. Nor did President Clinton’s NAFTA promise that manufacturing would not suffer here at home. It did.

Given how much of our manufacturing has been sent offshore, it should come as no surprise that China accounts for many of the slowdowns in manufacturing and shipping. So many of the products we buy as Christmas gifts come from China, including books, 90% of which are published in China. Add paper and glue shortages to the supply chain equation and books join hundreds of other products arriving late or on back order. Just recently, I interviewed an author who told me that even though his book was released on the publication date, there was a shortage in the bookstores thanks to supply chain issues.

The Biden administration already has the economic and political imperative to rally bipartisan troops in support of supply chain reform. An executive order Biden issued last February directing the National Security Council and the National Economic Council to study the vulnerability of America’s supply chains resulted in a task force of more than a dozen federal agencies to study the issue and the product of their efforts is hardly light reading.

Their report, “Building Resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American Manufacturing, and Fostering Broad-Based Growth,” identifies four supply chains in need of reform: semiconductor manufacturing, large capacity batteries, critical minerals and materials and pharmaceuticals. Another report will be issued next month addressing energy and communications technology.

These are all vulnerable supply chains, but the place to start should be health care products and pharmaceuticals. We learned the hard way during the pandemic that basic protective gear like N95 facemasks, critical ventilators and personal protective equipment were in short supply, and rumors were flying that China was deliberately holding them back from the global supply chain.

Andrew Mulcahy, a senior policy researcher for health care at the RAND Corp., points out that many chemicals that U.S. pharmaceutical companies use in manufacturing their drugs are made in China and India. Too often, they get hung up by disruptions around shipping thanks to labor shortages and other issues.

Bringing manufacturing back to America makes sense beyond meeting our health care needs and assuring Americans in the future that we will not be caught again flatfooted by a future pandemic. It also creates good-paying jobs for American workers, often better salary and benefits than the service sector provides.

Then there’s the issue of what substandard conditions workers in other countries endure to produce goods for the American marketplace. Congress passed a bill requiring companies to prove that goods imported from China’s Xinjiang region were not produced with forced labor. The irony here is that many of the largest companies such as Coca-Cola, Apple and Nike opposed the bill complaining that it would disrupt global supply chains, which is even more reason to bring more manufacturing back to the States.

The National Manufacturing Guard Act, passed with bipartisan support, invests $1 billion to mitigate future supply chain emergencies and it also sets up the Office of Supply Chain Preparedness to develop industry partners that will respond to crises with ample resources for the nation’s needs.

It’s no wonder that Democrats and Republicans can come together on supply chain reform. What can be more American than returning jobs stateside and rebuilding a manufacturing base that weighs in currently under its fighting weight.

As Congress and the president plot our future in manufacturing, they will have to invest in manufacturing training for workers whose jobs have sailed off to China, leaving too many workers in jobs that do not require the latest manufacturing skills, such as additive manufacturing, known more commonly as 3-D printing.

This election year is the perfect moment to urge our elected officials to continue with the work underway to reform the supply chain. No excuses, no delays and certainly no partisanship when it comes to encouraging companies to reinvest in manufacturing here and equipping Americans with the know-how to produce critical products stateside rather than rely on distant supply chains and countries who do not have our best interests uppermost in mind.

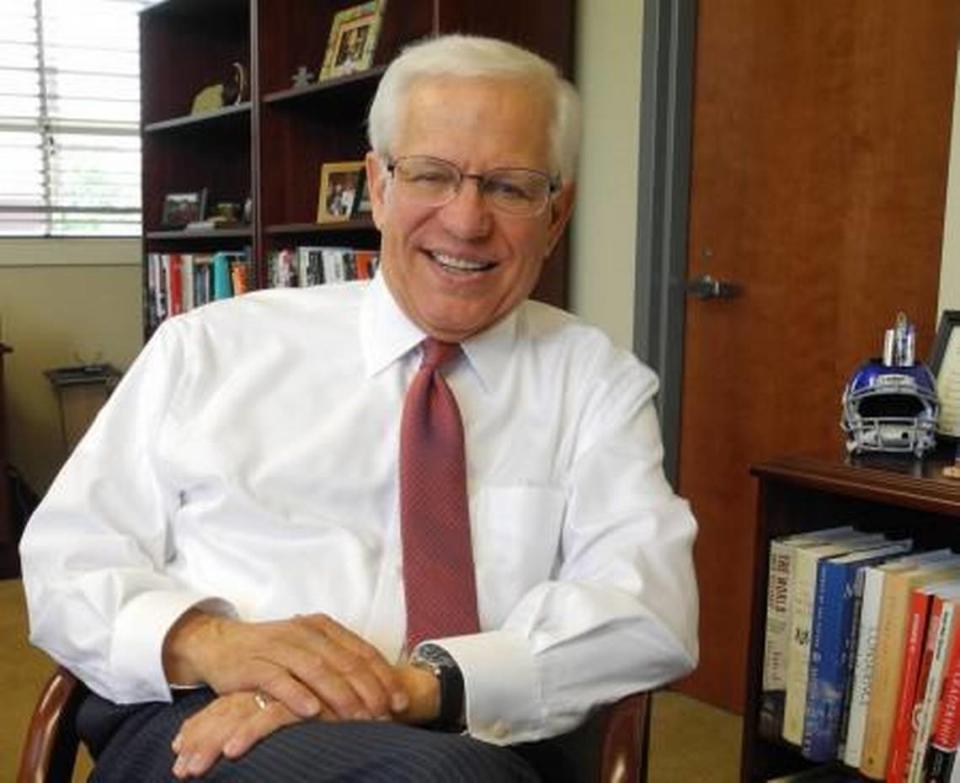

Bob Kustra served as president of Boise State University from 2003 to 2018. He is host of Reader’s Corner on Boise State Public Radio and is a regular columnist for the Idaho Statesman. He served two terms as Illinois lieutenant governor and 10 years as a state legislator.